Story

Ungendered: The Women in

Painting Toward Architecture

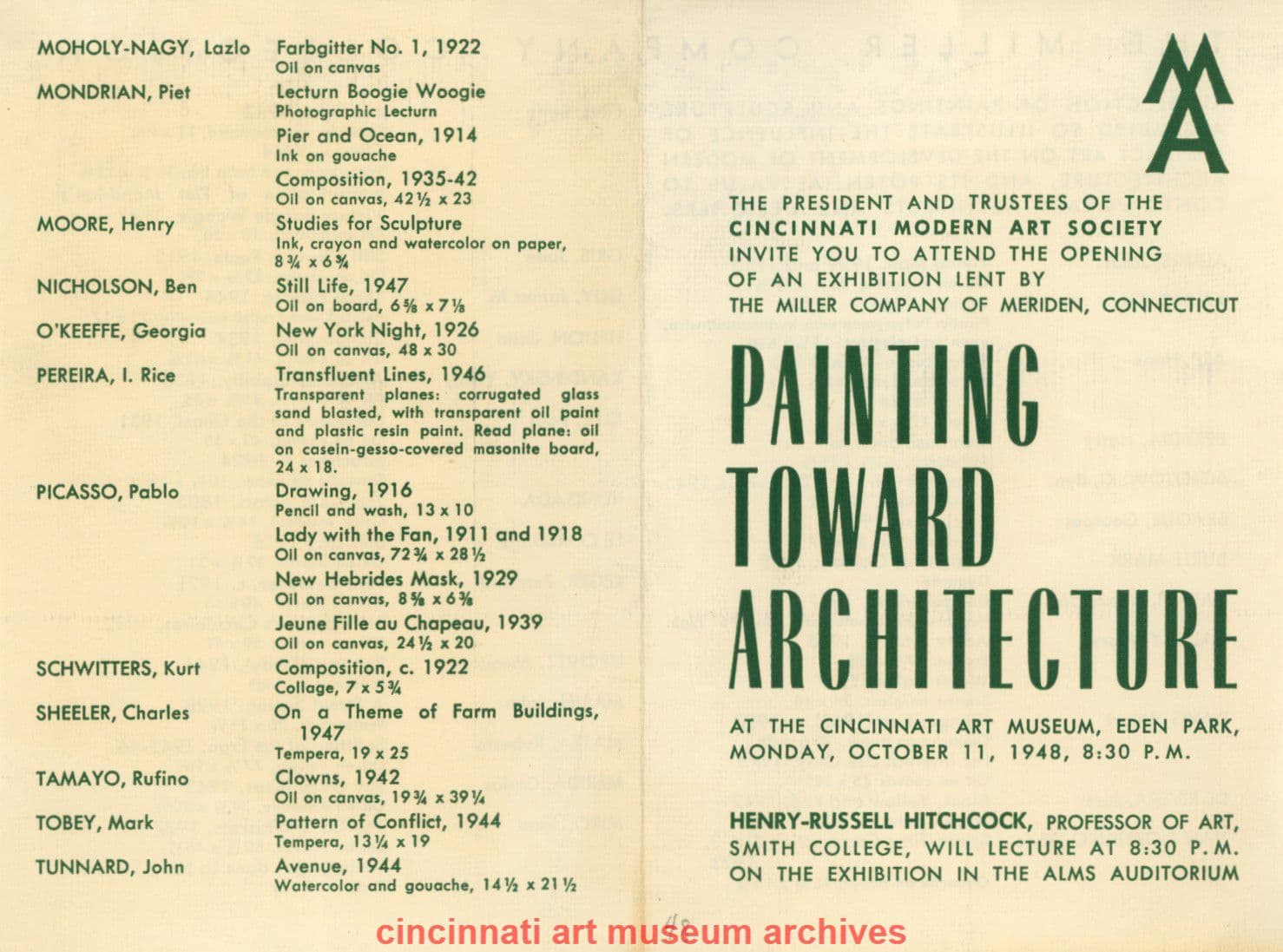

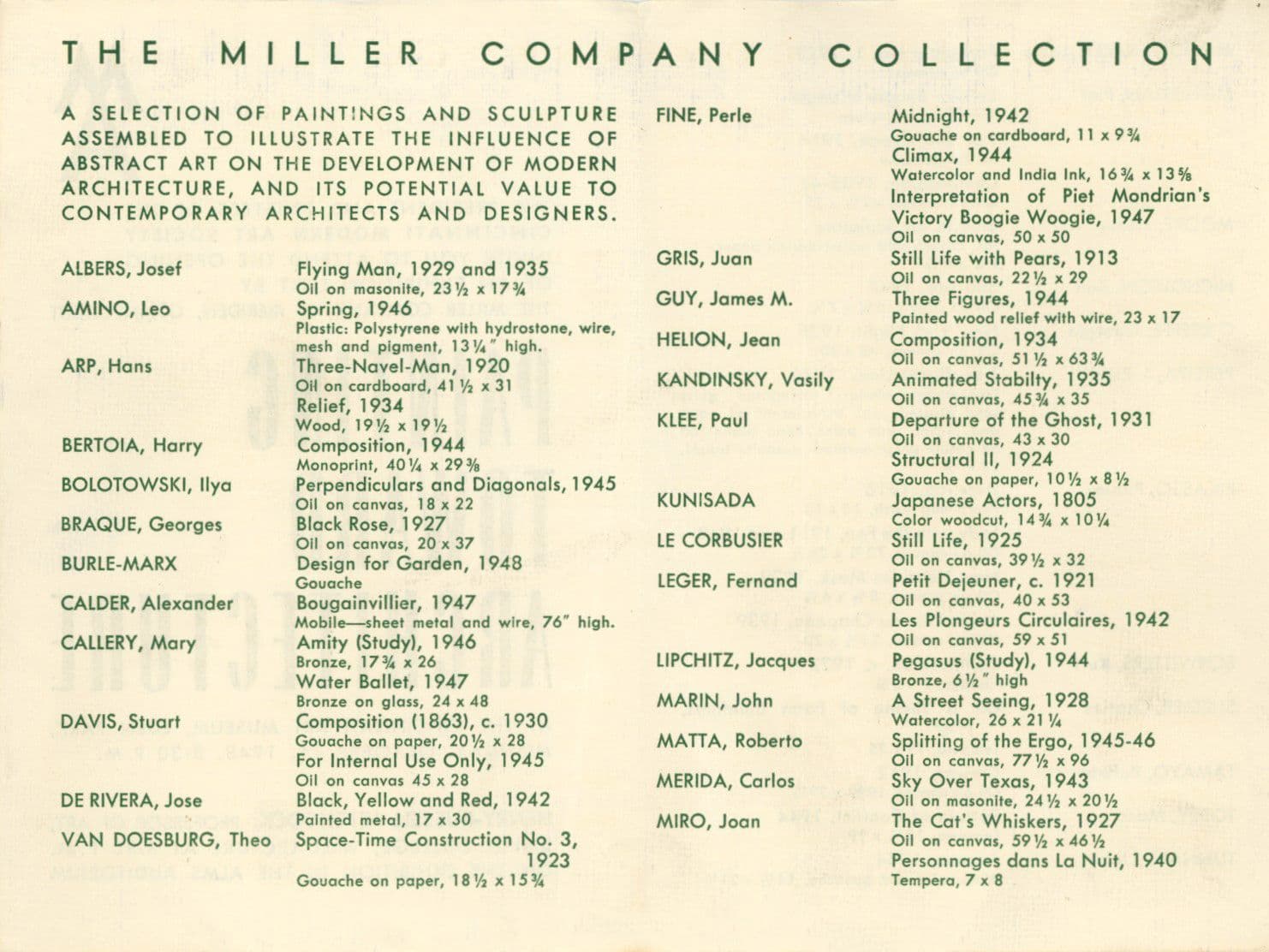

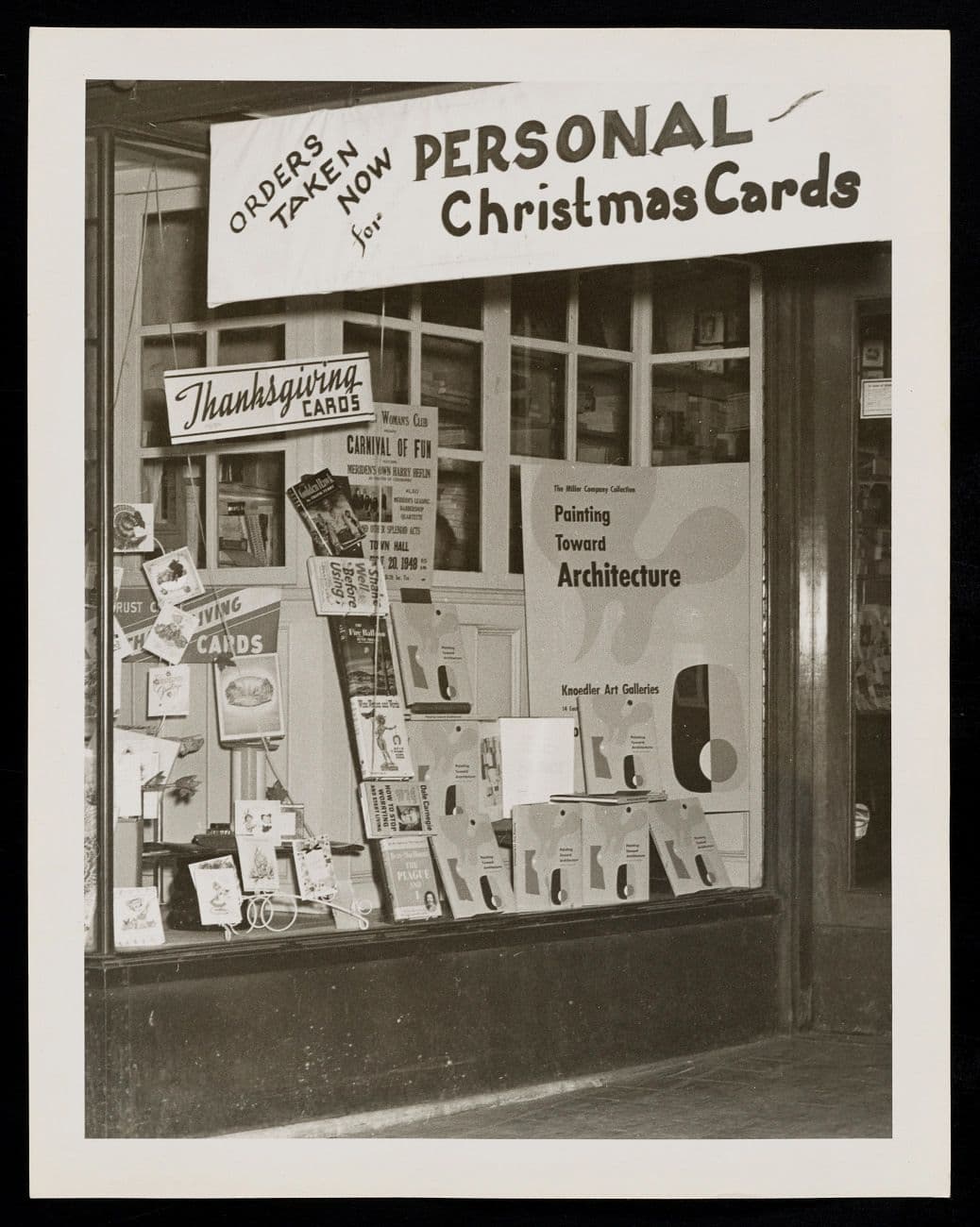

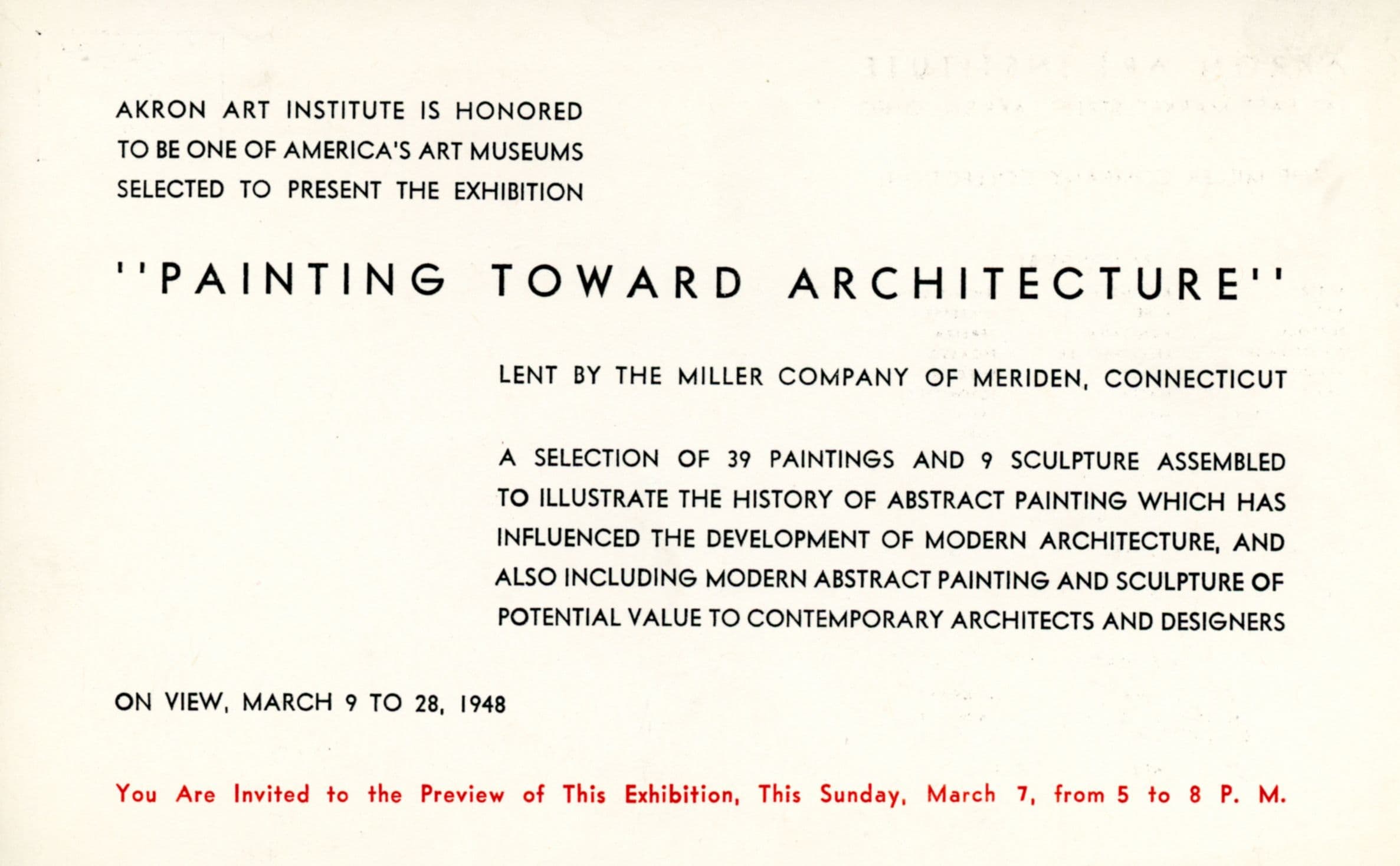

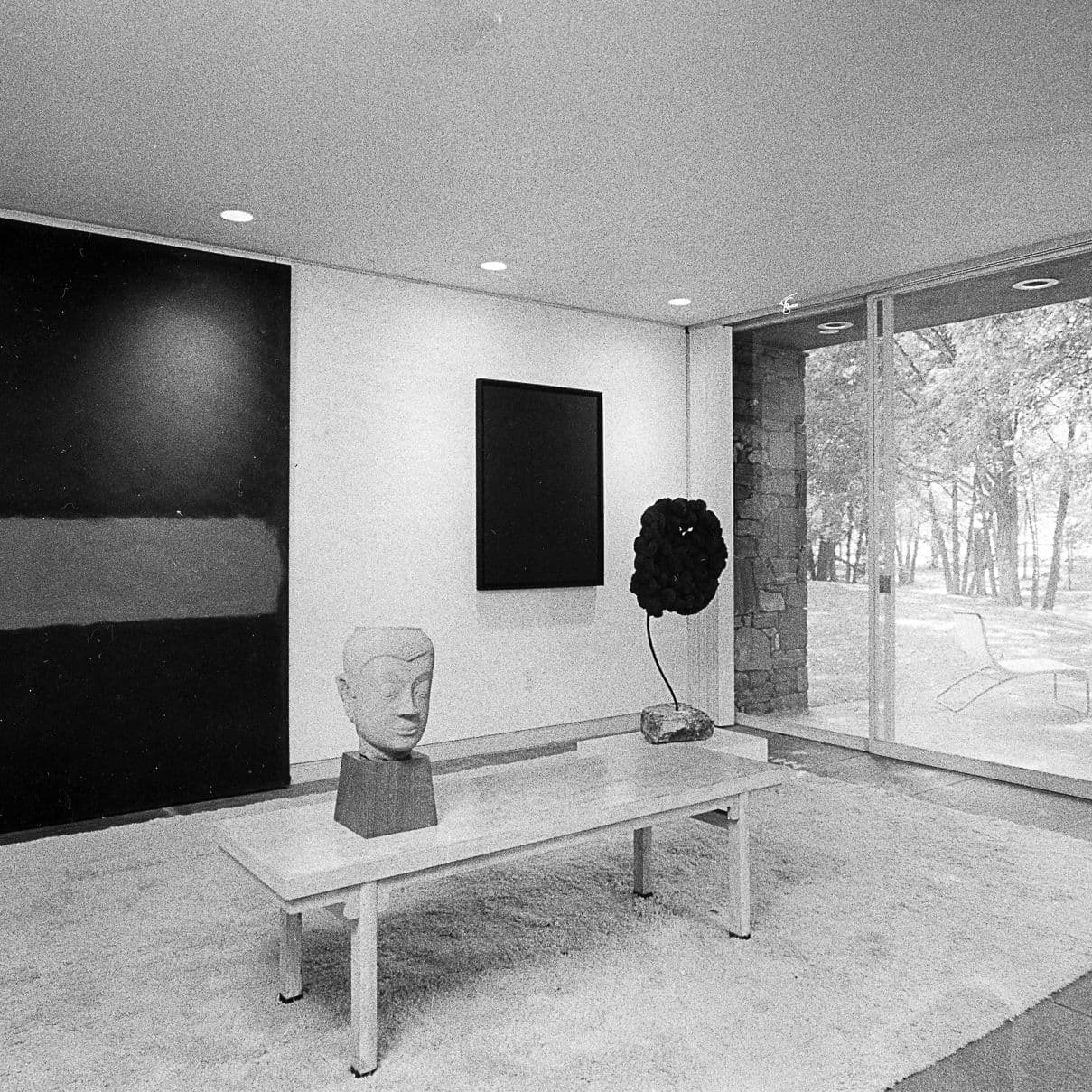

The provocative exhibition of the Tremaine collection titled Painting Toward Architecture, which opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut in December 1947, left an indelible mark on artists and architects who were at the start of their careers. Then known as The Miller Company Collection for the lighting firm owned by Burton Tremaine, it traveled to more than 28 venues, many on college campuses, encouraging visitors to ponder the connection between modern art and architecture.

I had a very clear idea that painting had been a strong influence on architecture or I never would have suggested it. And then of course I was looking for paintings that definitely backed up the ideas, and the more I would look, the more I would see relations that I hadn’t seen before.

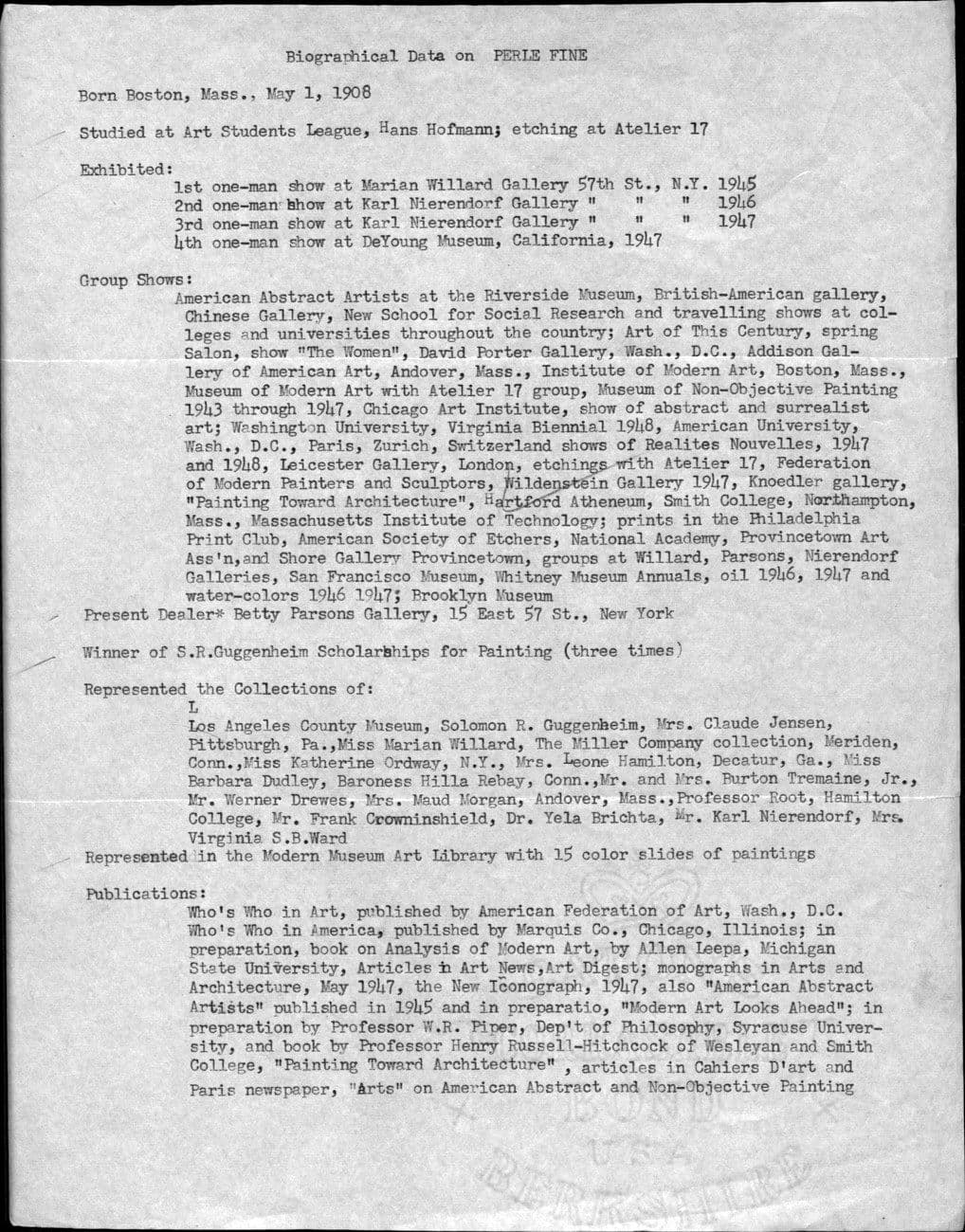

One unusual aspect was that four of the 39 artists and sculptors were women: Mary Callery, Georgia O’Keeffe, Irene Rice Pereira, and Perle Fine. That might seem like an absurdly low number. However, most exhibitions at this time did not include women. Even Peggy Guggenheim, one of the most cutting-edge art dealers in New York City in the 1940s, did not include many women in her trendy exhibitions at her Art of This Century gallery. Hedda Stern recalled that Guggenheim was so negative toward women that she hung her kitchen pans on a painting by Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

Male art dealers and critics were even worse. When the artist Buffie Johnson invited her friend James Stern, art critic for The New York Times, to attend the 31 Women exhibition at Art of This Century—one of only two such exhibitions Guggenheim put on—his answer was insulting: “There has never been a first-rate woman artist, a first-rate woman writer. Women were made to create with their bodies, and I am not going to look at thirty-one women’s paintings.” According to Johnson, “That was the end of a beautiful friendship.”

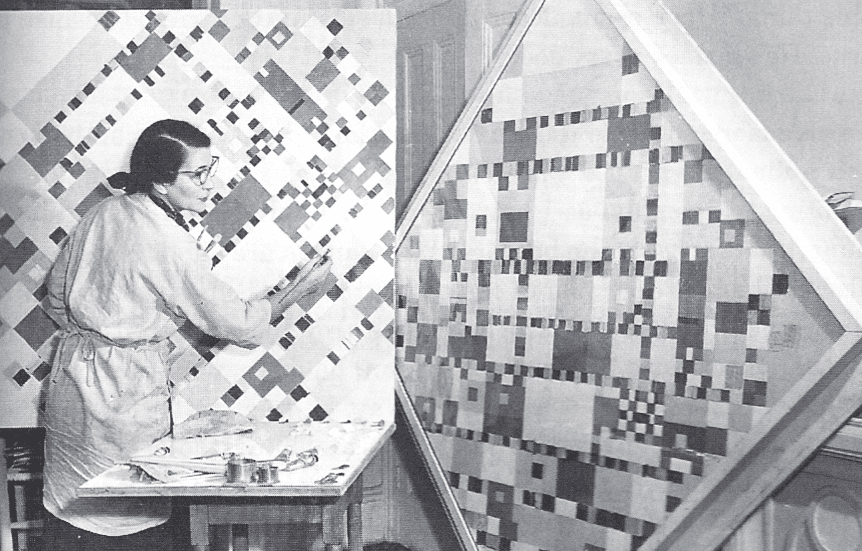

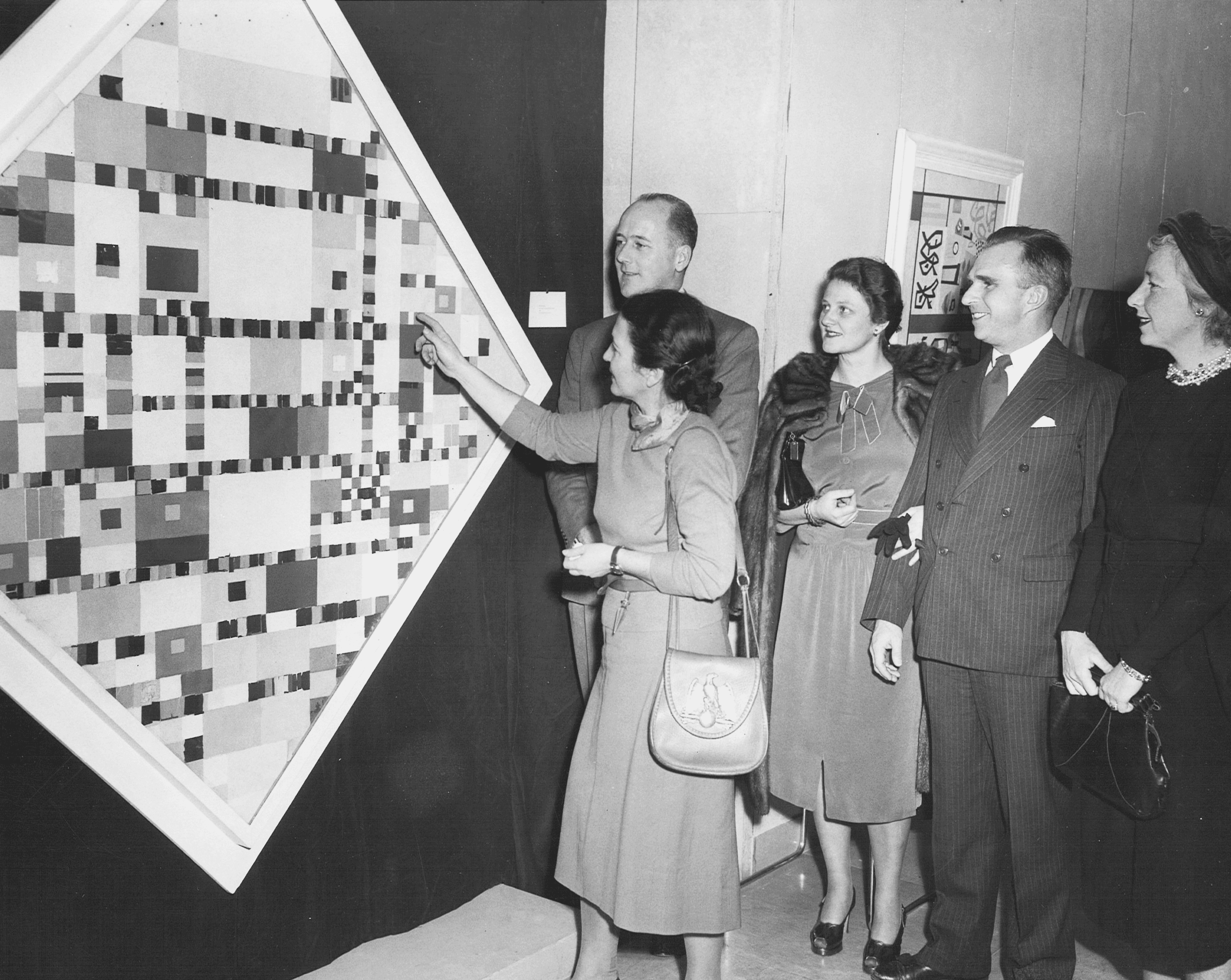

Perle Fine painting an interpretation of Piet Mondrian's Victory Boogie-Woogie. Photo courtesy of Maurice Berezov ©A.E. Artworks, LLC.

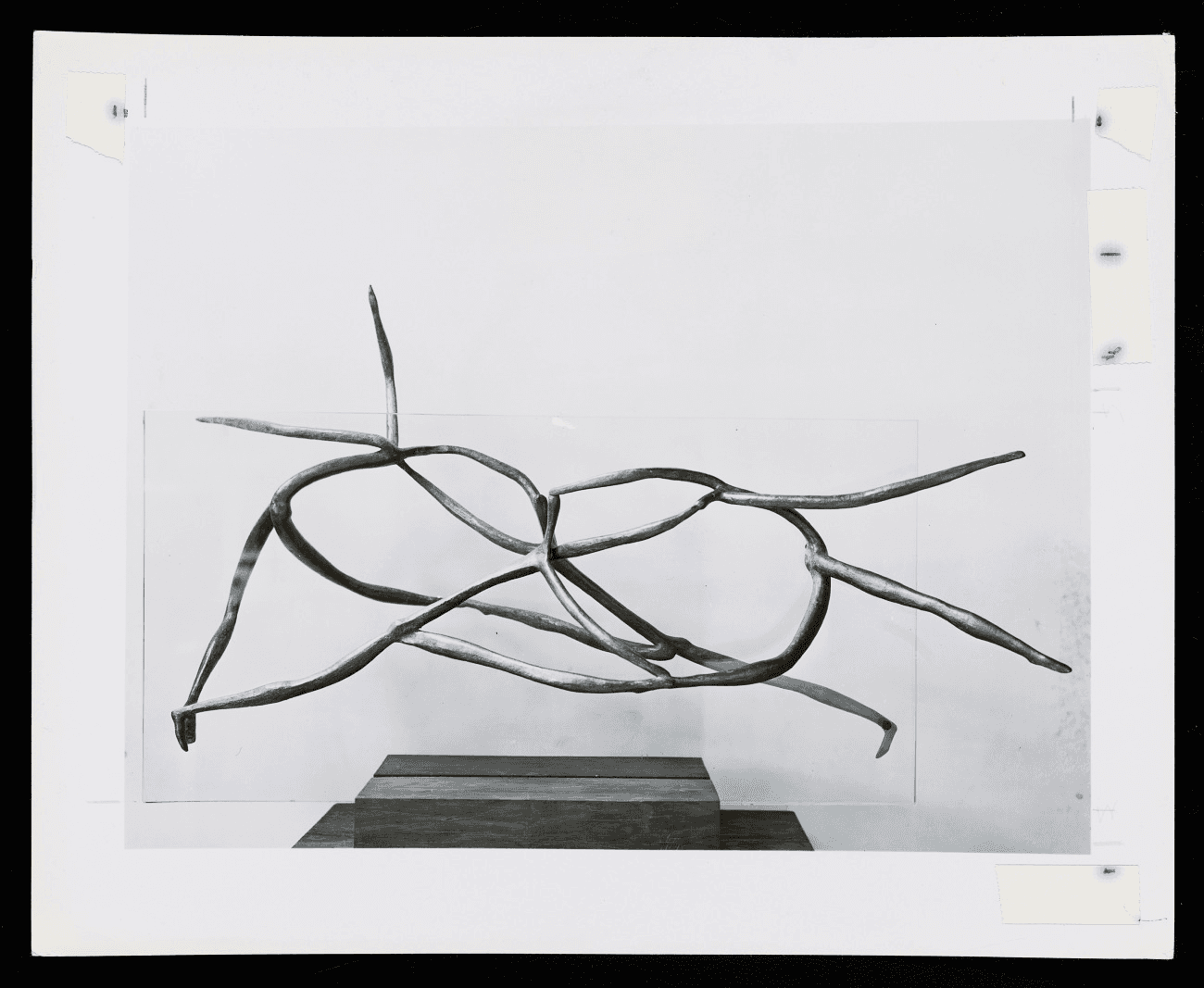

Mary Callery, Water Ballet, 1947. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

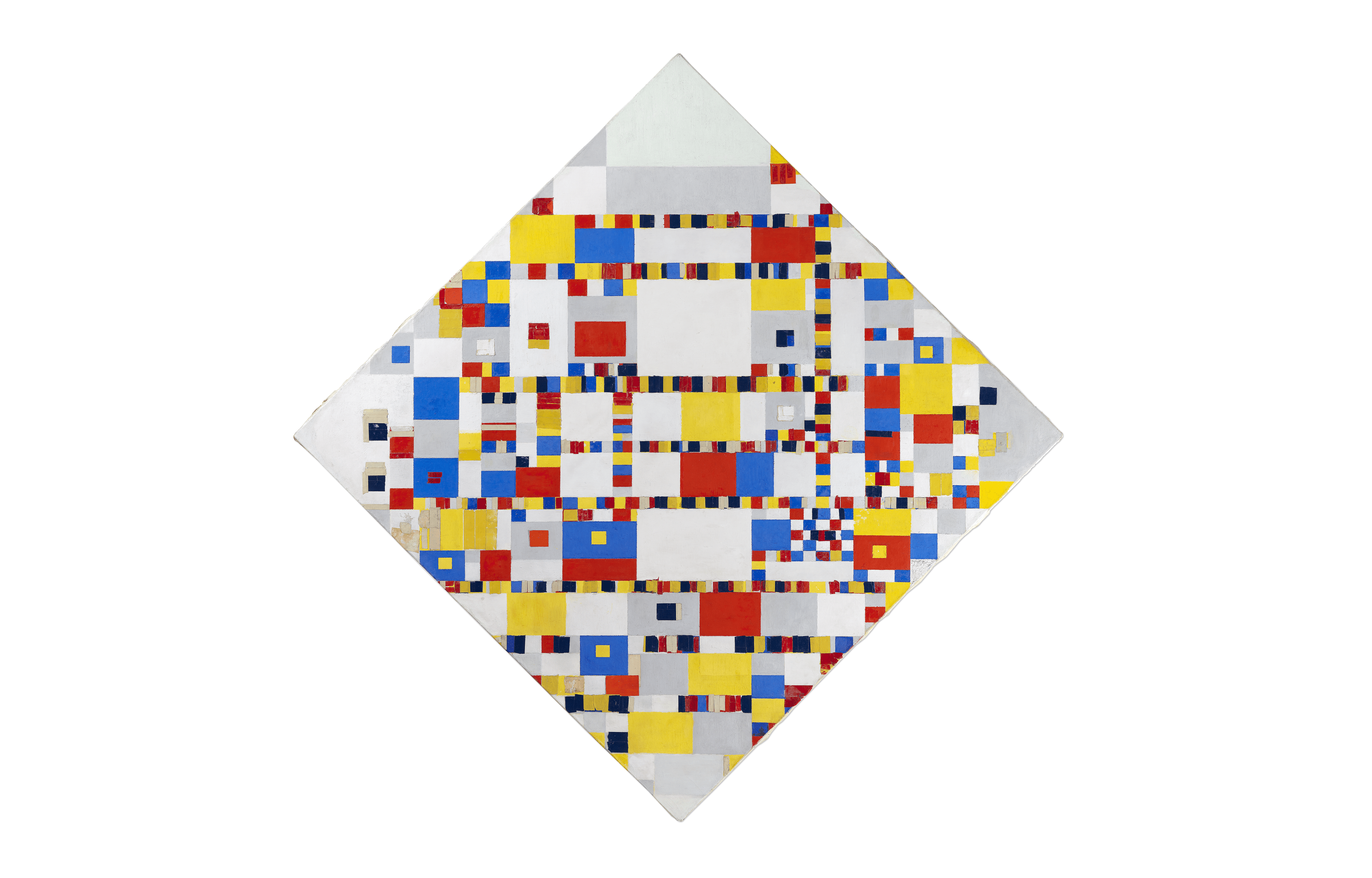

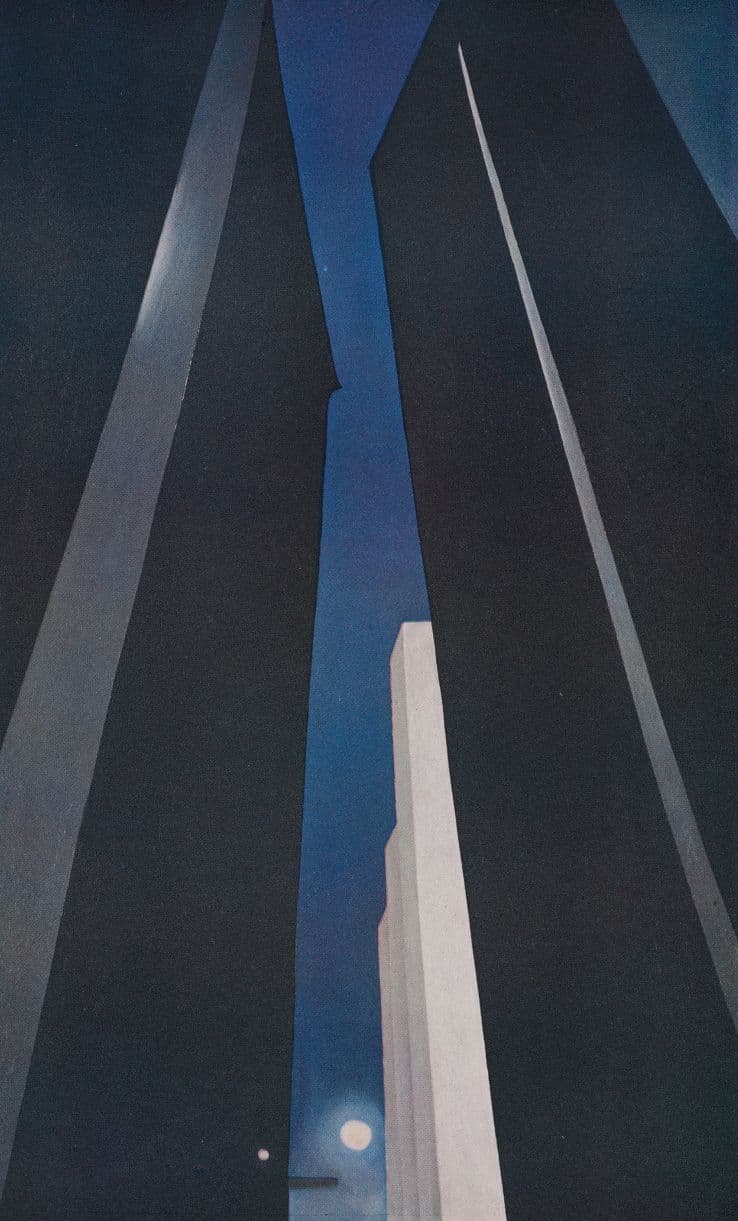

The inclusion of four women was notable, but so also was the equitable manner in which their work was shown. There was no mention of gender in the catalog. When the exhibition was at the Houston Contemporary Arts Association in 1950, Callery’s Water Ballet was at the entrance. O’Keeffe’s New York Night was placed on a hanging panel. Fine’s interpretation of Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie was prominently displayed.

With high regard for Fine’s skill and knowledge of Mondrian’s abstract concepts, Tremaine had commissioned her to paint the interpretation because the original was too fragile to go on the lengthy tour, yet it was too important to be left behind. Just before falling ill in 1944, Mondrian had attached tape to the completed canvas to experiment with the placement of the planes, but he had died before he could finish it.

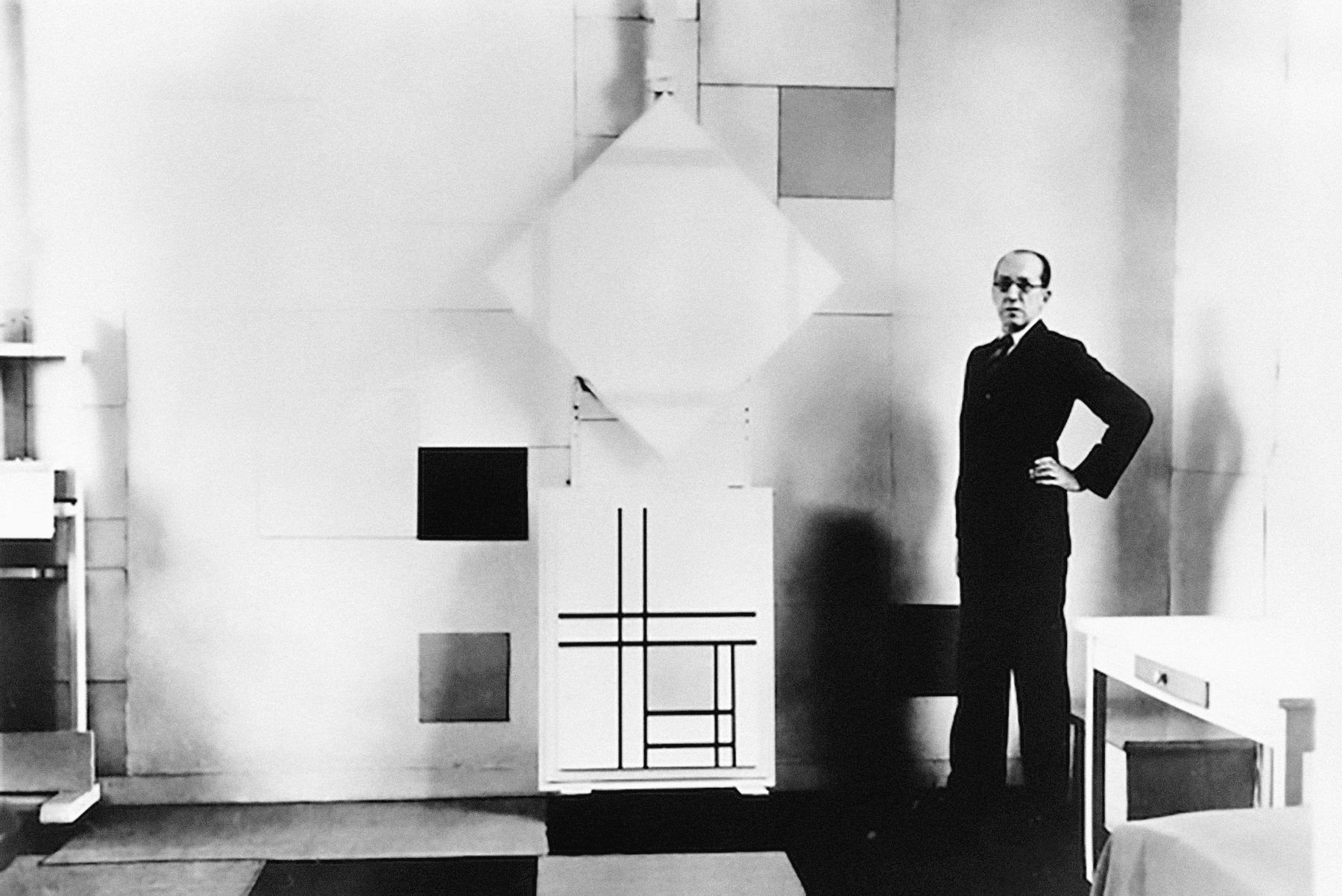

Piet Mondrian in his studio.

Background: Piet Mondrian in his studio with (top) Lozenge Composition with Four Yellow Lines (1933) and (bottom) Composition with Double Lines and Yellow (1934), Paris, October 1933. ©2024Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Foreground: Piet Mondrian, Victory Boogie-Woogie, 1944. Image courtesy of Kunstmuseum Den Haag, long-term loan Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands / Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

One other woman played a key role. Her initials M.C.R. appear repeatedly in the catalog identifying her as the writer of most of the commentaries. The easy-to-miss initials stood for Mary Chalmers Rathbun, director of exhibitions at Wesleyan University, who stepped in when the art historian Vincent Scully had to resign due to demands on his time at Yale. Her full name appears in the acknowledgments along with the name of the art director of The Miller Company, Emily Hall Tremaine.

Before taking a closer look at Rathbun and the artists, it is important to consider Tremaine herself. While she hired the best experts in the field of art and architecture—a true dream team—she was the one who made the final decisions as to what to acquire and what paintings would go on tour. Without a doubt she was the power behind the exhibition.

Painting Toward Architecture, text by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, 1948. Image courtesy of the Tremaine Foundation.

Emily Hall Tremaine, nee Emily Hall von Romberg, circa 1920s-circa 1930s. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Years after Painting Toward Architecture, the highly regarded art dealer Leo Castelli paid Tremaine the highest compliment. He said in an interview for Archives of American Art (Smithsonian) that there were all sorts of motivations for collecting art including financial gain but the strongest motivation is “real understanding, sometimes unconscious understanding of what the painting is about, what the painting is.” In that rarefied category, he placed Tremaine.

That “understanding” was evident by the mid-1940s with Tremaine’s acquisition of major works by modern European masters, among them Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, and Pablo Picasso. She was also fully aware of what American painters and sculptors were doing, acquiring works by Alexander Calder and Stuart Davis.

Perle Fine's interpretation of Piet Mondrian's Victory Boogie-Woogie in the Painting Toward Architecture exhibition. Image courtesy of the Tremaine Foundation.

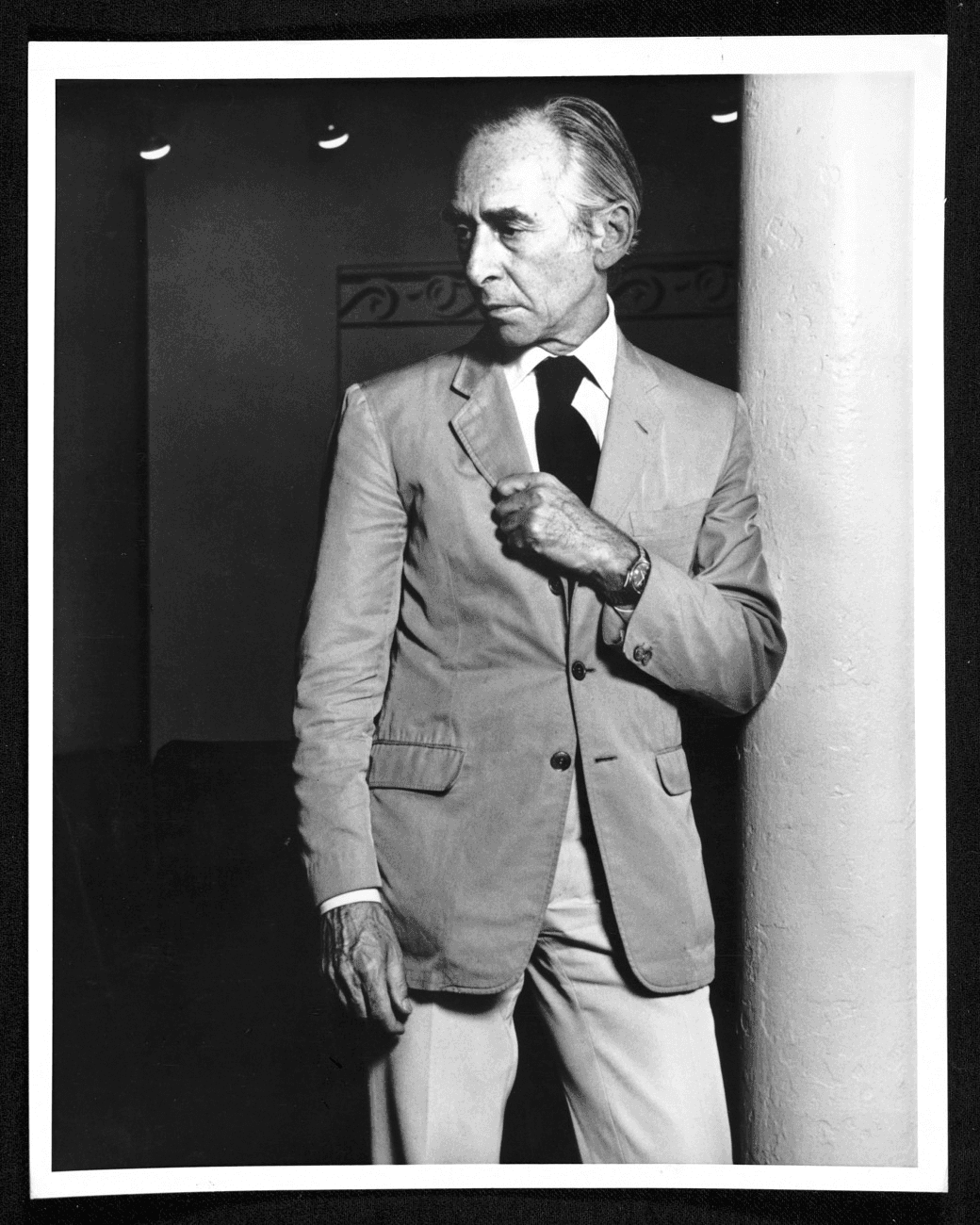

For example, her relative A. Everett “Chick” Austin, the charismatic director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, encouraged her interest in modern art, but it was Tremaine who demanded he come to New York to see Victory Boogie-Woogie, telling him that “every door that Mondrian closed he has opened again.” It was to Austin that Tremaine first broached the possibility of an exhibition. He enthusiastically enlisted the help of Russell Hitchcock who played a major role by theoretically connecting art and architecture.

Rathbun helped Tremaine mount the exhibition and produce the catalog. Formerly she had worked for the Addison Gallery of American Art at Philips Exeter in Andover, MA where she had curated a solo exhibition of Hans Hofmann’s paintings and co-wrote Layman’s Guide to Modern Art: Painting for a Scientific Age. To art historian Robert Rosenblum, the catalog was like a “thrilling manifesto, a sweeping overview” of the first half of the twentieth century.

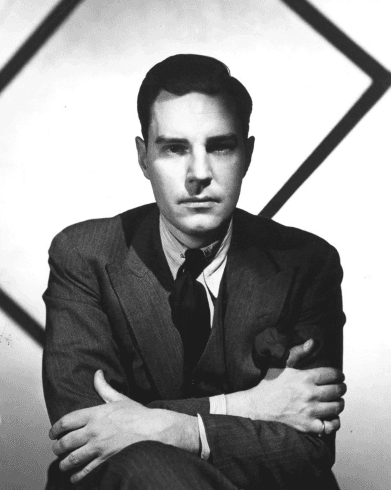

A. Everett (Chick) Austin. Photo courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum.

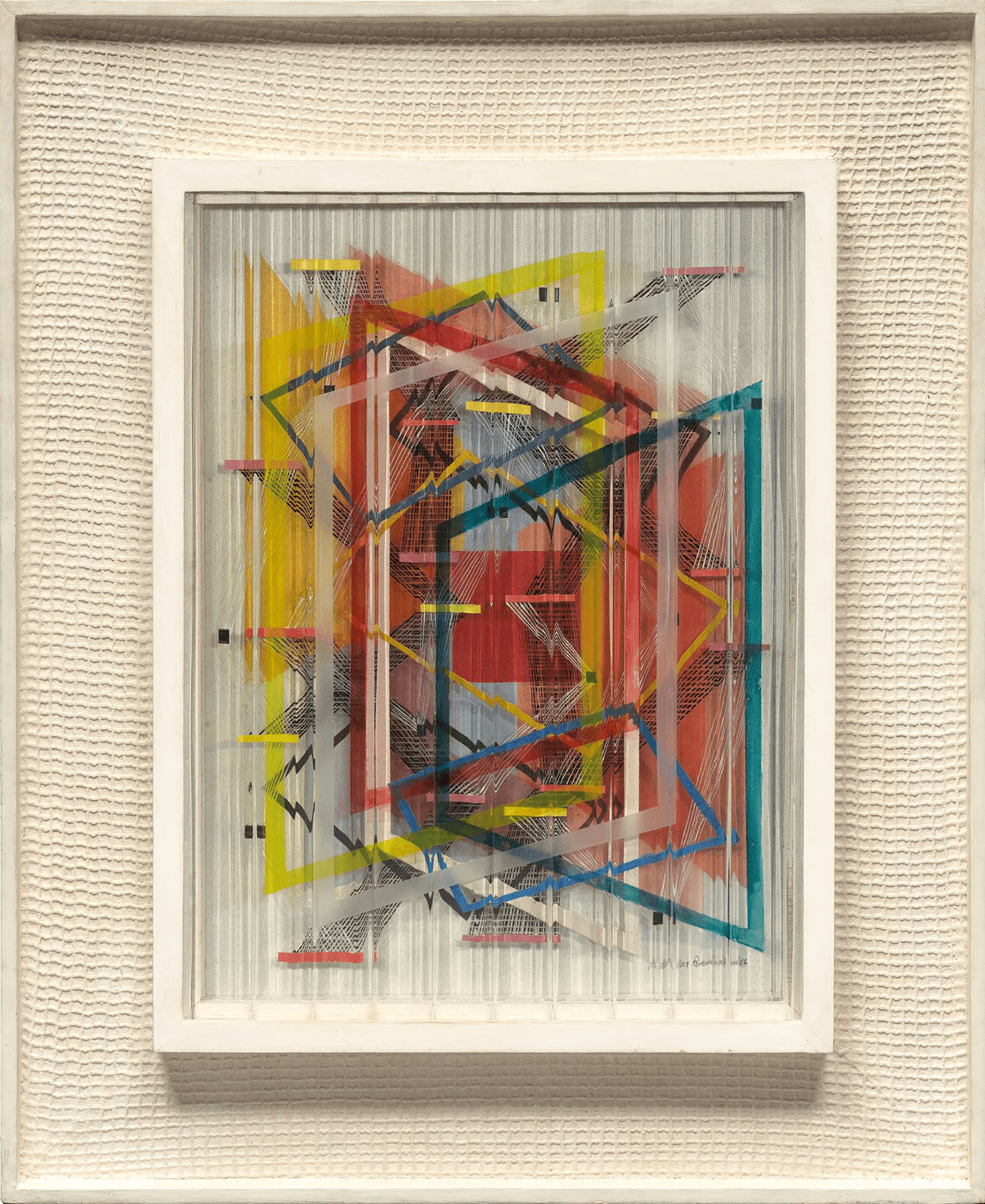

I. Rice Pereira Transfluent Lines. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine 1973.71.2, National Gallery of Art. © Estate of I. Rice Pereira / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The painting/bas relief Transfluent Lines (1946) by Pereira was a striking work constructed of corrugated and sand-blasted glass with transparent oil paint and plastic resin. “Transparency allows light to become an element of form in a relief composition as important as line, color and space,” Rathbun wrote.

From the Archives

From the Archives

Callery’s bronze sculptures Water Ballet and Amity (a study) were graceful, spare and whimsical. She had spent the 1930s in Paris spending time with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Combining bronze with glass, Water Ballet captured the sense of motion through clear water. As its name implied, Amity was of five figures holding hands. The Tremaines donated Amity to the National Gallery of Art.

About O’Keeffe’s New York Night (also titled City Night), there is a mystery. It was included in the catalog without any text, an omission that cannot be explained. Over the years, many other women would be represented in the Tremaine collection including Agnes Martin, Barbara Valenta, Betty Parsons, and Hilary Heron. Late in her life, Tremaine said that after half a century of collecting, it had become “a quest for the sublime.” For her, the sublime had no gender.

Georgia O'Keeffe, New York Night, 1926. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: Painting Toward Architecture, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.