Story

Arne Glimcher: Friendship & a Shared Love of Art

that Illuminates the Tremaine Collection

Introduction and Interview by Kathleen Housley. It was conducted via Zoom, April 9, 2024 and lightly edited with explanatory data in brackets, June 2024.

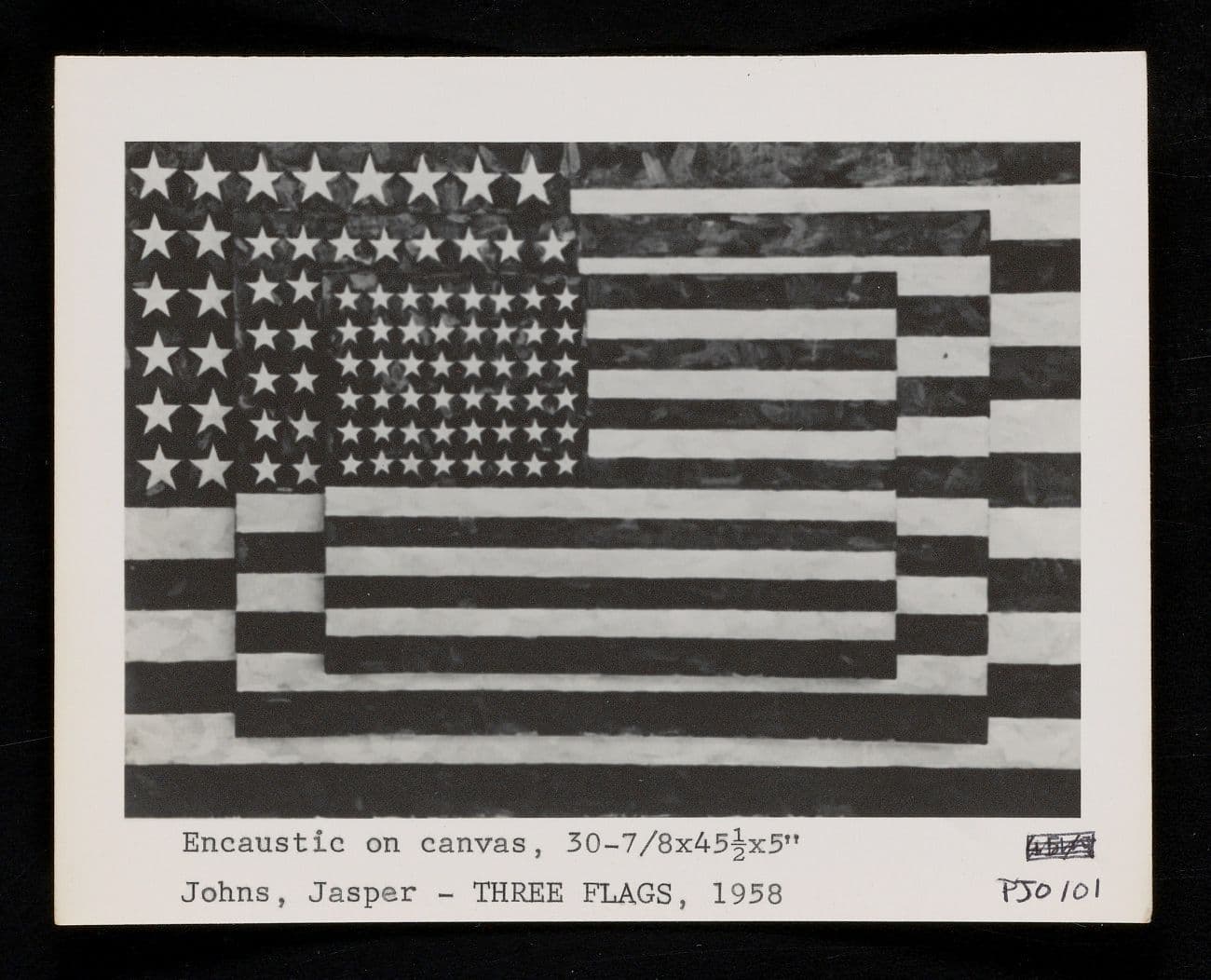

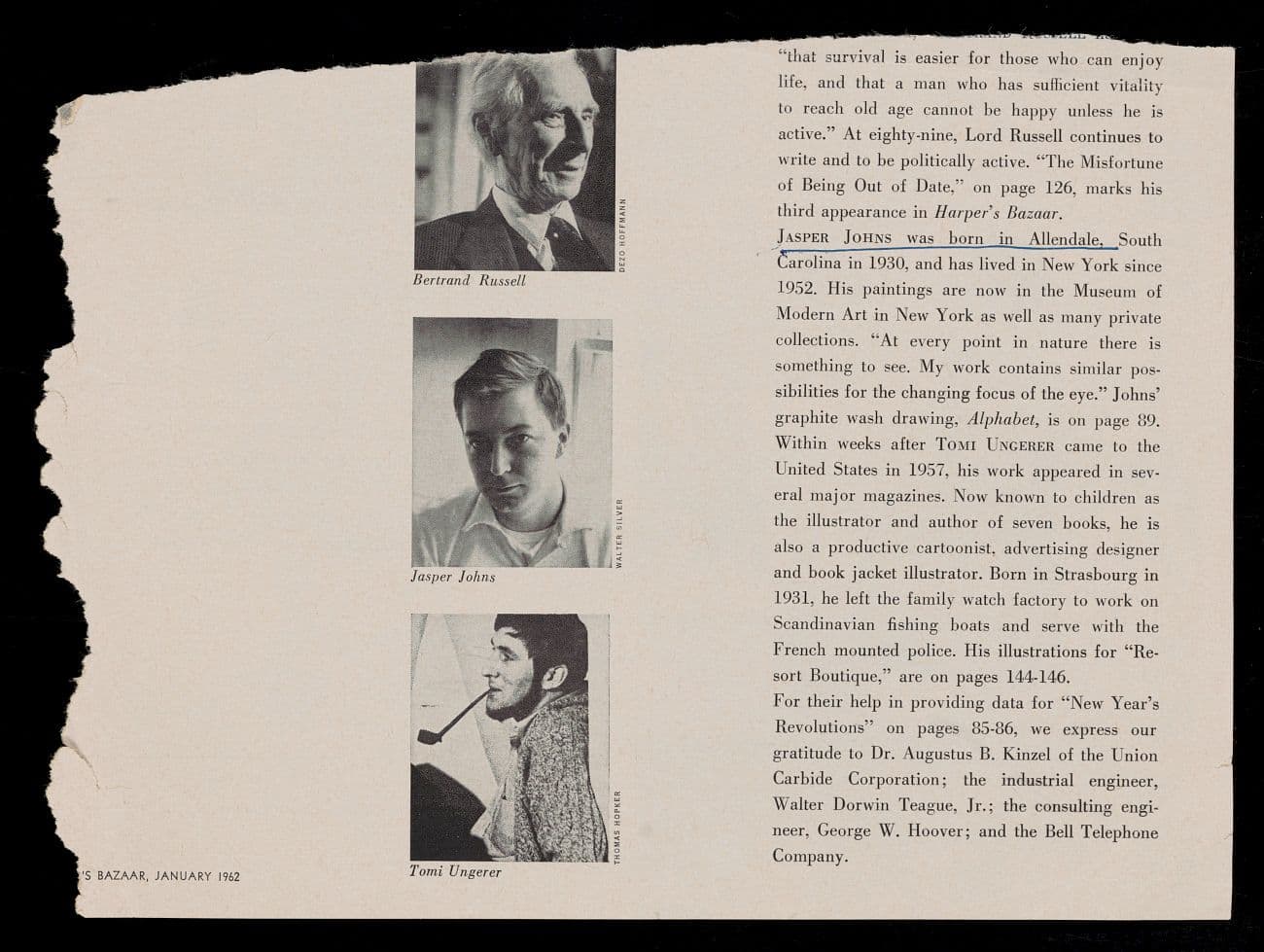

Arnold “Arne” Glimcher is the founder of the Pace Gallery, which was established in Boston in 1960, subsequently moving to New York City. Pace became a leading gallery that represented many important twentieth-century artists. For thirty years, Glimcher was both a friend and art dealer to the Tremaines. In 1970, he was instrumental in bringing about the $1,000,000 sale of Three Flags by Jasper Johns to the Whitney Museum of American Art. That sale made headlines. However, in the long-run, what mattered to Glimcher was the exceptional love of art that he and Emily Hall Tremaine shared. He considered her to be one of the rare breed of collectors who recognized how modern art meshed with the cycle of art history, thereby, driving that cycle forward.

The Tremaine home with Three Flags by Jasper Johns on the far right. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; 🅮 Composition XX by Theo van Doesburg on far left; Poires et raisins sur une table by Juan Gris in the center, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Housley: Arne, when did you meet the Tremaines? Did they come up to Boston when the Pace Gallery was on Newbury Street [in 1960]? Did they come up for the show Stock Up for the Holidays? Or did you not meet them until you moved down to New York?

Glimcher: I met the Tremaines in Boston, but I don’t think it was for Stock Up for the Holidays, but maybe it was. I think they visited Boston and came into the gallery. In any city they were in, they would go into the galleries and just generally see what was happening on the scene in these various cities. Obviously, a huge part of their life was art, and it became integrated with their social life. So they had an art social life, and then, certainly, they had another social life that was much more a society social life.

A young Arne Glimcher in 1962 at the exhibition “Stock Up for the Holidays: An Anthology of Pop Art” at Pace Gallery, 125 Newbury Street in Boston. Credit...Jim Dine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Morgan Art Foundation Ltd./ARS, NY; Marisol; Claes Oldenburg; George and Helen Segal Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY; Estate of James Rosenquist/VAGA at ARS, NY; Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/ARS, NY; Estate of Tom Wesselmann/ARS and VAGA, NY

Housley: When you met them in Boston, already they were major collectors. The Mondrian [Victory Boogie-Woogie] had gone into their collection in the 1940s. Then in the 1950s, they added Kline, Newman, de Kooning, and Rothko. And then in 1961, Jasper Johns’s Three Flags went into the collection. By then they already owned Johns’s Tango, Device Circle, and White Flag.

Glimcher: Yeah, and the Delaunay disk [Premièr Disque by Robert Delaunay] was a treasure.

Housley: Absolute treasure. And that’s a wonderful story about how they got Premièr Disque, because it was offered to them by Robert Delauney’s wife, Sonia, to go with Victory Boogie-Woogie. She thought the two [paintings] should be together.

Glimcher: Together. Yeah.

Le Premier Disque by Robert Delaunay on the left and Victory Boogie-Woogie by Piet Mondrian on the right in the Tremaines’ home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Housley: So when you met the Tremaines, they already had a reputation. What was your first impression of Emily, and then how did that impression change as you became more involved with them with acquisitions?

Glimcher: Well, clearly, Emily ran the show. Burton was a lovely man—but how shall I say this and not make it sound negative because I don’t mean that—he was sort of a bumbling consort to an art world queen. And very, very lovable and very, very anxious to learn, asked lots of wonderful questions. But I don’t think he ever felt the art the way that Emily felt the art. I don’t know when exactly it started, but it was a time when there was a small art world. And Saturday mornings would be the time that we’d hope that the Lists or the Skulls or Emily and Burton would show up at the gallery, and it was a time that there were no other people influencing them. I was the expert on my artists. They didn’t bring in some expert to confirm their own impression of the work or quality of the work. And so, we would just talk and talk. So Saturday morning or afternoon, and sometimes late afternoon, we might spend two or three hours sitting in the viewing room and just talking about a painting. And then maybe the next Saturday they’d come back and say, “Let’s reserve it.” And the next Saturday they’d buy it or not. Most of the time, yes. And I would call and say, “this Brice Marden or this Agnes Martin, or whatever, is perfect for you and fits perfectly into the collection.”

“We became really good friends. We would go up and visit them in the country for Sunday lunch. Sometimes we’d even bring the kids. I remember once we brought Lucas Samaras for Sunday lunch. And sometimes on my way home, when I passed their place on the way up Park Avenue, I’d just stop. I’d ring the doorbell and say, “Are you guys there?” And Emily would say, “Come up for a drink.” And it was very spontaneous. So I visited often and we talked a lot about art, and they were incredibly supportive of me.”

And that [relates to] the true story of how the sale of Jasper Johns’s Three Flags happened. I was reading my friend Leonard Lauder’s book [The Company I Keep: My Life in Beauty, 2020], but that’s not at all how the sale of Three Flags happened for the Whitney Museum of American Art. It began when I was [at the Tremaines] one evening, and Emily had been very unsatisfied with the National Gallery. She had given the National Gallery a lot of work, and she never saw it hanging. But I must say in all honesty, she didn’t give the National Gallery a lot of great work. She gave the National Gallery of Art a lot of secondary work, and they kept accepting things in the hope for the great paintings, like Three Flags or like Victory Boogie-Woogie or like Delaunay’s Premièr Disque, or that fantastic tam-tam [Oceania] they had. And so she would complain and complain about that a lot, and she said to me one day, “I don’t think museums appreciate anything unless they paid for it, and the higher the price, the better.” I told her I didn’t believe that. I disagreed with her. But we were good friends, I could disagree.

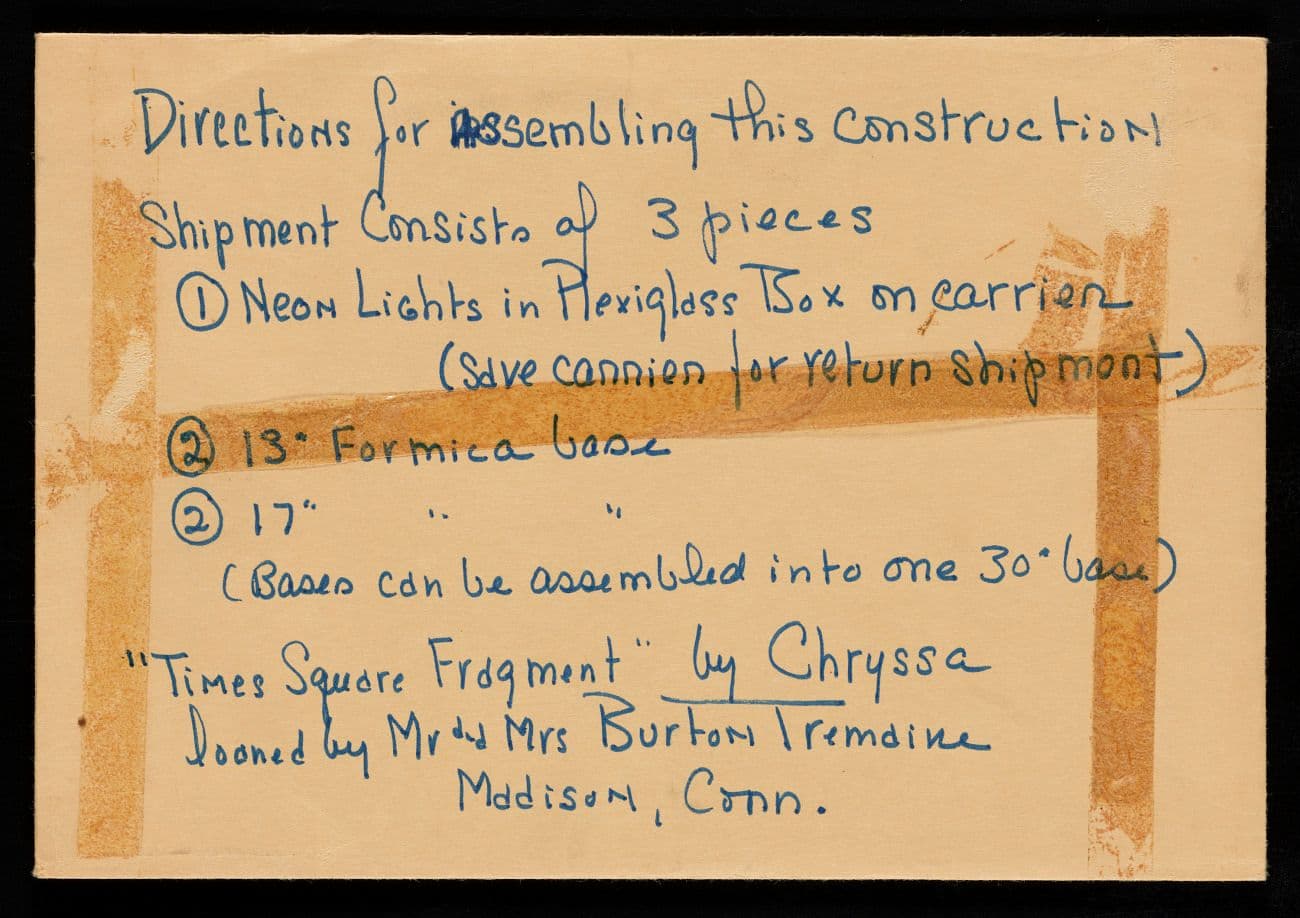

Housley: Before we get too far into Three Flags, which is a big story, there were a lot of paintings after you moved to New York that the Tremaines acquired through the Pace Gallery that they loved. In 1965 and in 1966, and this is not a complete list, there was Chryssa’s Fragments to the Gates of Times Square, Lucas Samaras’s Box #51, which Burton loved, and Trova’s Falling Man series, which they eventually ended up giving to the Wadsworth Atheneum, and that’s three in about a three-month period.

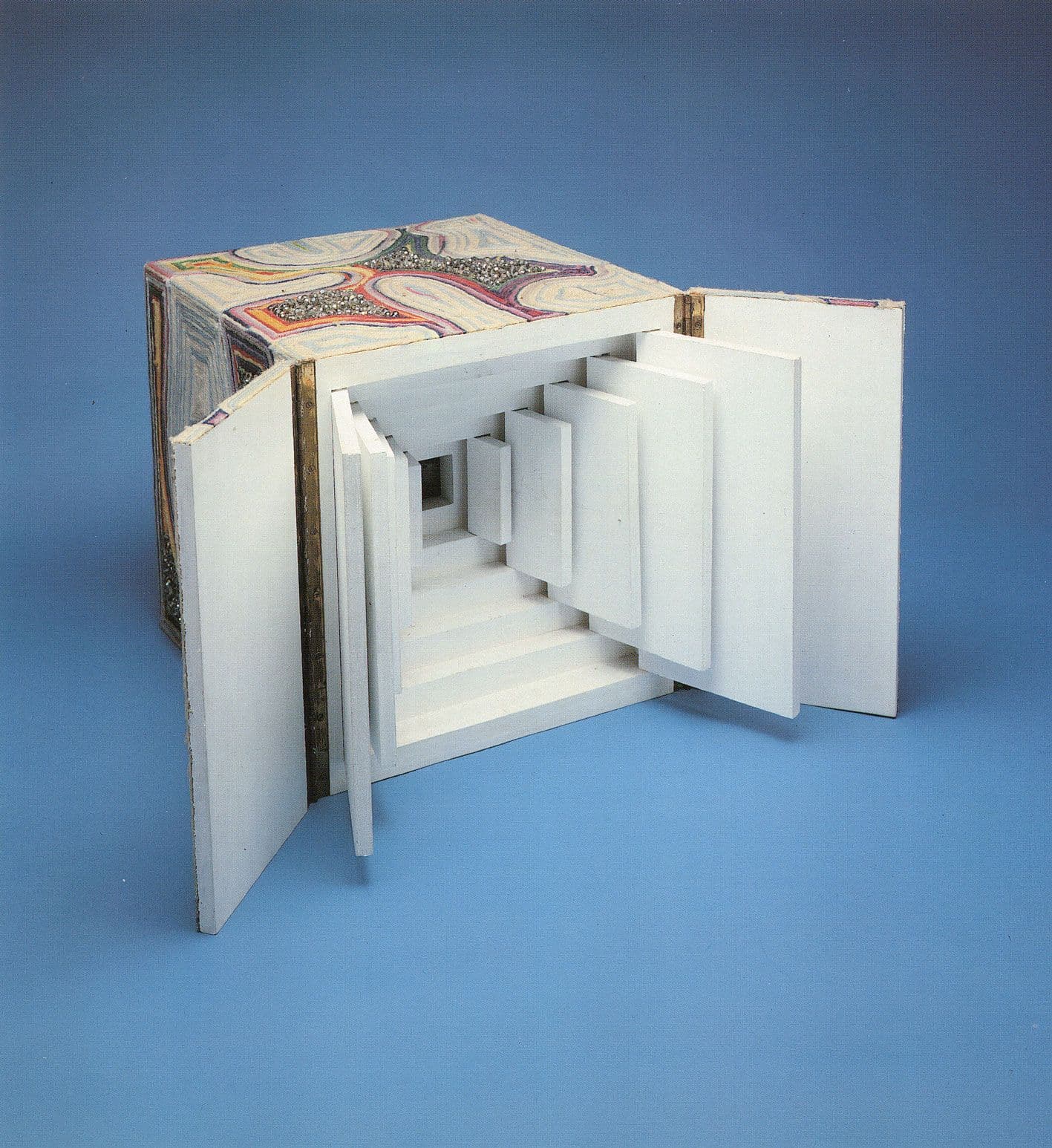

Lucas Samaras, Box #51, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, © 1988 Christie’s Images Limited

Glimcher: They were buying from several shows one right after the other, but they had wonderful taste and they didn’t wait for an advisor. They knew what they liked and they would pull the trigger so to speak. So we became great friends.

Housley: She read a lot of art history. In your Archives of American Art [Smithsonian] interview, you mentioned about sitting down on Saturday mornings with them and how you appreciated that collectors would take the time to talk to you. Emily took the time to look. She’d go to artist studios. She would talk to artists. That’s how she first linked up with Jasper Johns, because she went to his studio. And later on, she thought that was so important that when she and Agnes Gund became friends, that is one of the things she taught Agnes to do—to go into the studios. Could you talk about that a little in terms of collectors then and collectors now?

Glimcher: Collectors now are too busy making money, and art is too expensive, so they have other concerns. I mean, if Emily and Burton were spending $10,000 or $25,000 on a work of art, it was still significant money, but it wasn’t a great amount of money to them, and it wasn’t to a lot of people of extreme wealth. Today, when the painting is $10 or $20 million, or $5 million, the people who are buying it are people of enormous wealth who don’t have time to come to the galleries. They’re too busy making money. That’s what they do. And so, many of the collectors now are part of the financial world, and are willing to have somebody go to the galleries for them, choose something, see pictures of it and buy it. That happens in our gallery, but I personally have never sold a work of art from a picture. I won’t do it. I’m not interested in anyone buying art from me who doesn’t care about it or doesn’t see it. I think I can afford that. I always felt that way. So why not now? But Emily also read about it.

Burton G. Tremaine and Emily Hall Tremaine at their Madison, Connecticut house. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Sculpture pictured at left is Water Ballet by Mary Callery. Sculpture in background is Salem #7 by Antoni Milkowski. Sculpture at right is Falling Man Series: Wheelman by Ernest Trova.

You see, the Tremaines were the only people, like the Bergmans from Chicago—these were educated people in the art world. These were people who were learned in the classical sense of the word. They knew where the piece they were buying fit into the cycle of art history, or hoped it fit into the cycle of art history. So that’s different. Today, we’re dealing mostly with people who don’t have that knowledge. We’re dealing with people who like art a lot. But it was Emily’s career. That’s a different thing. It was Linda Macklowe’s career. When that auction sold, it was her taste. And the Skull auction was their taste. It was a very different world. Smaller, more intimate, and much nicer.

And the dealers were different. We never thought we’d get rich. I mean, whoever thought we’d get rich? You wanted a life in art. You loved art. Your friends were the artists. My friends weren’t bankers and people like that. My friends were all the artists I’ve championed all of my life. And that’s what my wife and I wanted—a life in art. And that’s what we got. And I don’t know what happened; it just ran away from us. And here we are in this big gallery. But the expansion of this gallery is more [the achievement of] my son Mark than me.

“You see, the Tremaines were the only people, like the Bergmans from Chicago—these were educated people in the art world. These were people who were learned in the classical sense of the word. They knew where the piece they were buying fit into the cycle of art history, or hoped it fit into the cycle of art history. So that’s different. Today, we’re dealing mostly with people who don’t have that knowledge. We’re dealing with people who like art a lot. But it was Emily’s career. That's a different thing.”

Housley: Let me ask you a question about the pop era in the early 1960s. Emily had said in her Archives of American Art interview [conducted by Paul Cummings, 1973] that they had visited Oldenburg and his Ray Gun store, and then they had visited Warhol. And then she said, “We saw Jimmy Dine’s work and Tom Wesselmann and Jim Rosenquist and Lichtenstein. Once or twice we invited these boys to our apartment. And in several instances, they had not yet met one another. I remember in particular that Rosenquist met Lichtenstein for the first time here.” Now, I don’t have a date for that, Arne. I presume it was probably late 1961, early ‘62.

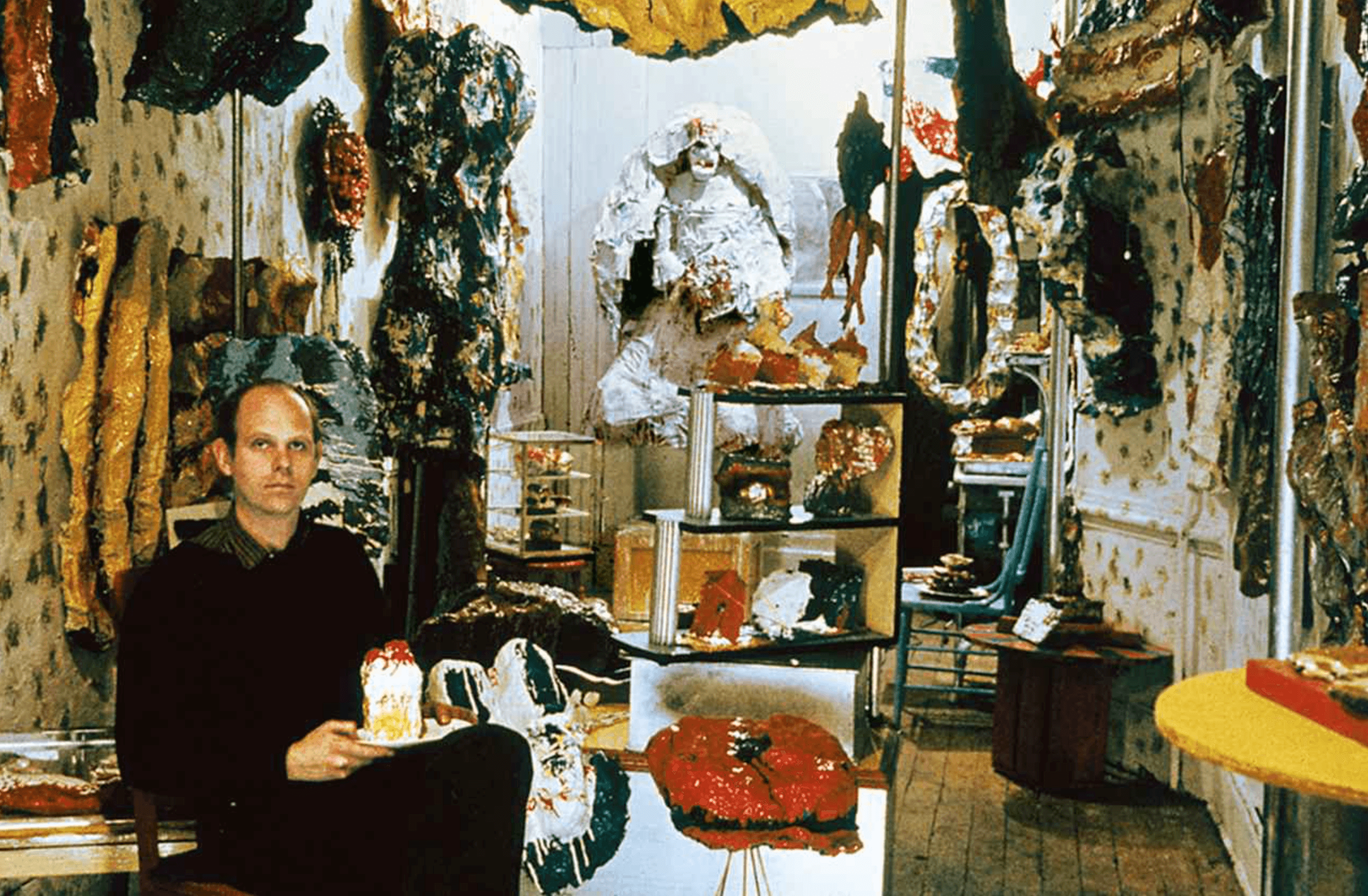

Claes Oldenberg, The Store, 1961. Public Domain.

Glimcher: Exactly. It had to be because by ‘63 they knew each other. When I moved to New York, all of those guys knew each other. And Jim Dine and Oldenburg from 1959 were the closest of friends and were in the same gallery. Oldenburg had a lot of the posters, the drawings for posters that Jim Dine made. It was a very chummy group. But at that point, they were all in different galleries.

Housley: Some of them didn’t have any gallery.

Glimcher: Yeah, but at the Reuben Gallery was Oldenburg and Dine, and I think Whitman, and I can’t remember all the artists. But when they coalesced, mostly at Leo Castelli’s, they were already established. Eleanor Ward showed so many people. Warhol was Eleanor Ward’s artist. She discovered him. Leo took him very late. And I was showing Warhol in Boston before Leo was interested in him. In fact, he wasn’t interested in him, I remember. And Jim Dine was with Martha Jackson. So, it would be really nice to set the record straight at some point, because Martha Jackson and Eleanor Ward were the two most important people. They had some money to invest. I think Eleanor Ward had a backer. Martha Jackson was from the Kellogg cornflake family.

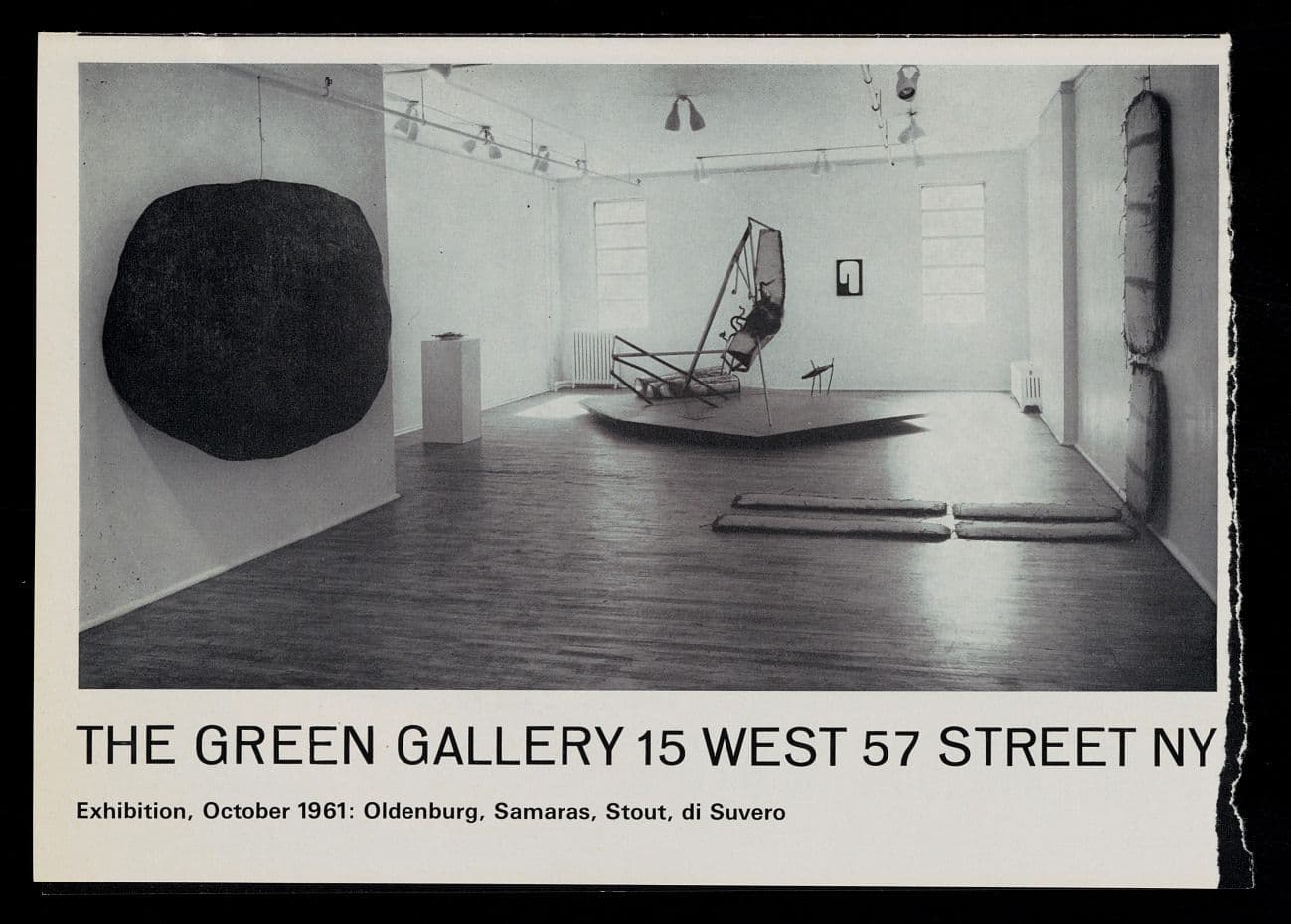

Housley: What about the Green Gallery? Is the Green Gallery in there too?

Glimcher: Yeah. The Green Gallery opened a year before we did. But it only lasted for about two or three years.

Housley: Okay. Because the Tremaines had several paintings from that period of time.

Glimcher: They had Oldenburg, Bob Morris, Donald Judd. Dick Bellamy [the Green Gallery] had a brilliant eye. They had Lucas Samaras. He had discovered Lucas. And when he closed, a lot of the artists came to the other galleries, and that’s when things coalesced in different places.

The Green Gallery: Exhibition, October 1961: Oldenberg, Samaras, Stout, di Suvero. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Housley: You’ve mentioned Samaras already who was with you in Madison, so I was just going to follow up. These parties at which the Tremaines mixed artists with oftentimes other collectors. They were trying—promote is probably not the right word, to expose—these artists to other collectors. Were you at any of them? Do you remember?

Glimcher: Yeah, absolutely. And dealers. I mean, I remember Ivan Karp at one of their parties, and Ivan was a really terrific influence on Emily as he was on everybody in those days. It’s not a coincidence that Castelli became the biggest contemporary gallery when Ivan Karp left Martha Jackson and went to Leo. Ivan was the head of the Martha Jackson Gallery. Then he left and went to Leo’s and Leo became such a big gallery. But Martha was great. There’s so much today about, I’ve read about, where the women were not in the art world. On the contrary, all the dealers practically were women. It wasn’t a very manly job. It was mostly gay men and women.

Housley: Was Betty Parsons still dealing in the ‘60s? She was mostly in the ’50s, wasn’t she?

Glimcher: No, she was in the ‘60s too. She went into the ‘70s. And she was right across the street from my gallery.

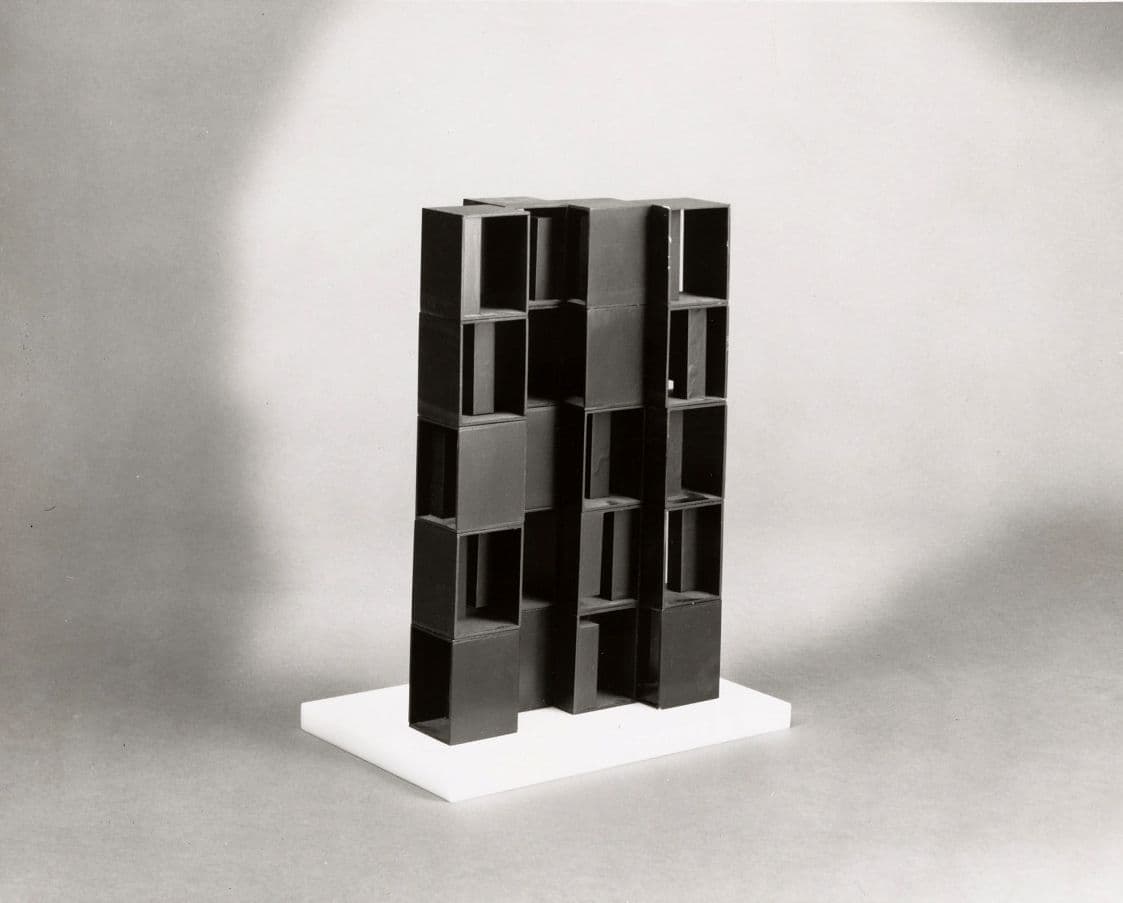

Louise Nevelson, model of Atmosphere and Environment II, black lucite. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Housley: So you have brought up the women, which brings up Nevelson, because Emily really liked Louise Nevelson’s work. Actually, she liked Nevelson too. She had gone to the Grand Central Moderns Gallery to Nevelson’s 1958 show and had bought several pieces out of that show. And then you showed Nevelson in Boston early on. But one of the things that I’d love to have your opinion of is this: in my book on Emily, I called her a neologist. In other words, the new was very critically important for her. She said at one point, Arne, and it’s an important statement, “I would prefer to see what’s coming through the artist.” And that’s one of the reasons why she wanted to go into the studio. She wanted to see what was coming through the artist, the process of art, not just the art itself. Yet with Nevelson—to whom she wrote a beautiful letter, I think she had visited Nevelson’s house filled with sculpture—once she bought the three or four works from Nevelson, Emily never bought anything after 1961. It’s not that she was over Nevelson, but she moved on.

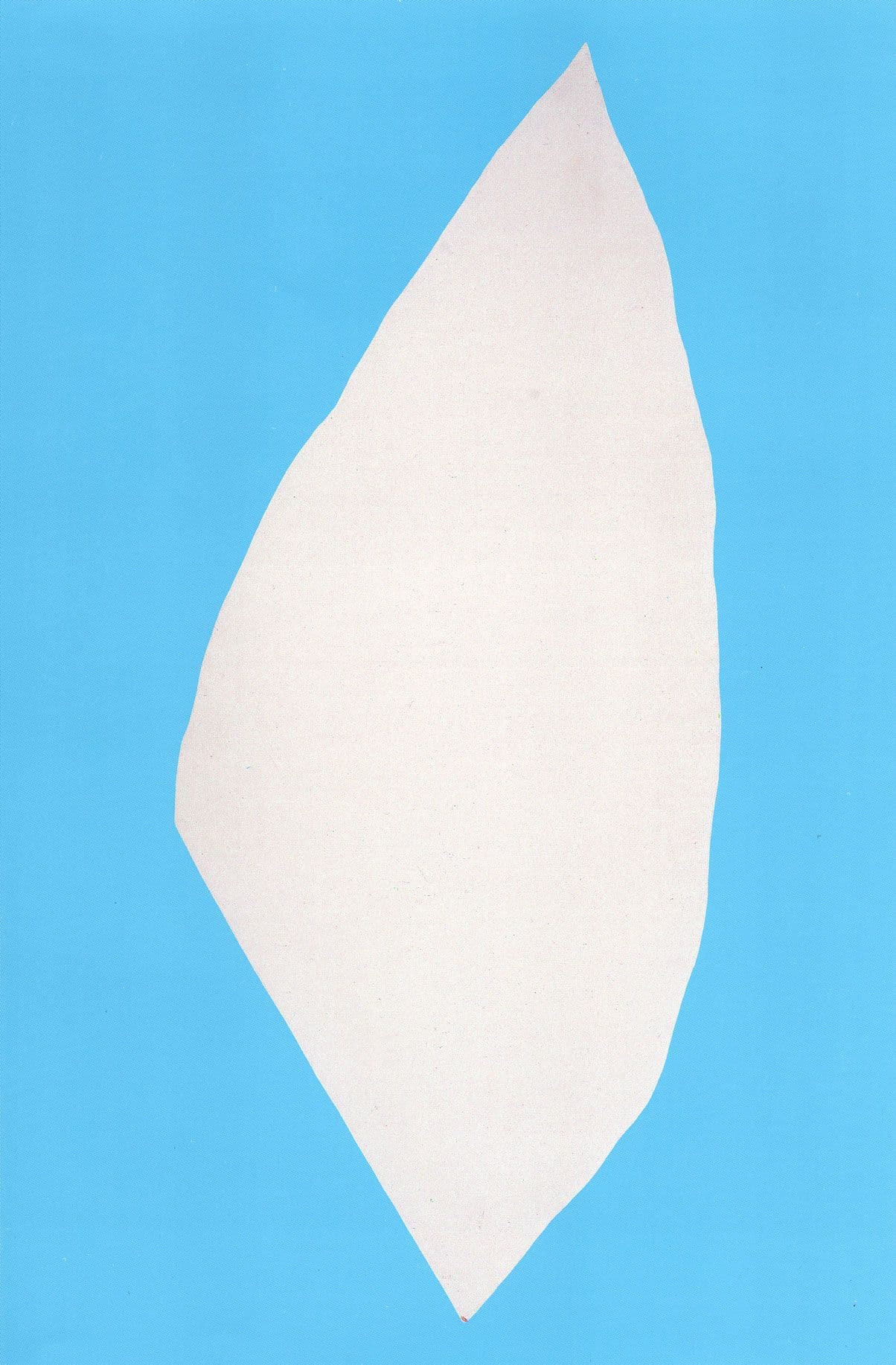

Richard Tuttle, Mist, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, © 1988 Christie’s Images Limited

Housley: Tuttle says the same thing about visiting and seeing his work and what it meant to get that affirmation of this work not being completely out there, but still within a line of…

Glimcher: …within the history of artistic achievement. That was a great piece. I mean, that’s one of the great Tuttle’s of all time. And she was incredibly brave to buy that picture. I mean, it was super minimalistic at a time before minimalism. [In 1964, 5he Tremaines acquired The Fisherman from the artist.

“Within the history of artistic achievement. That was a great piece. I mean, that's one of the great Tuttle’s of all time. And she was incredibly brave to buy that picture. I mean, it was super minimalistic at a time before minimalism.”

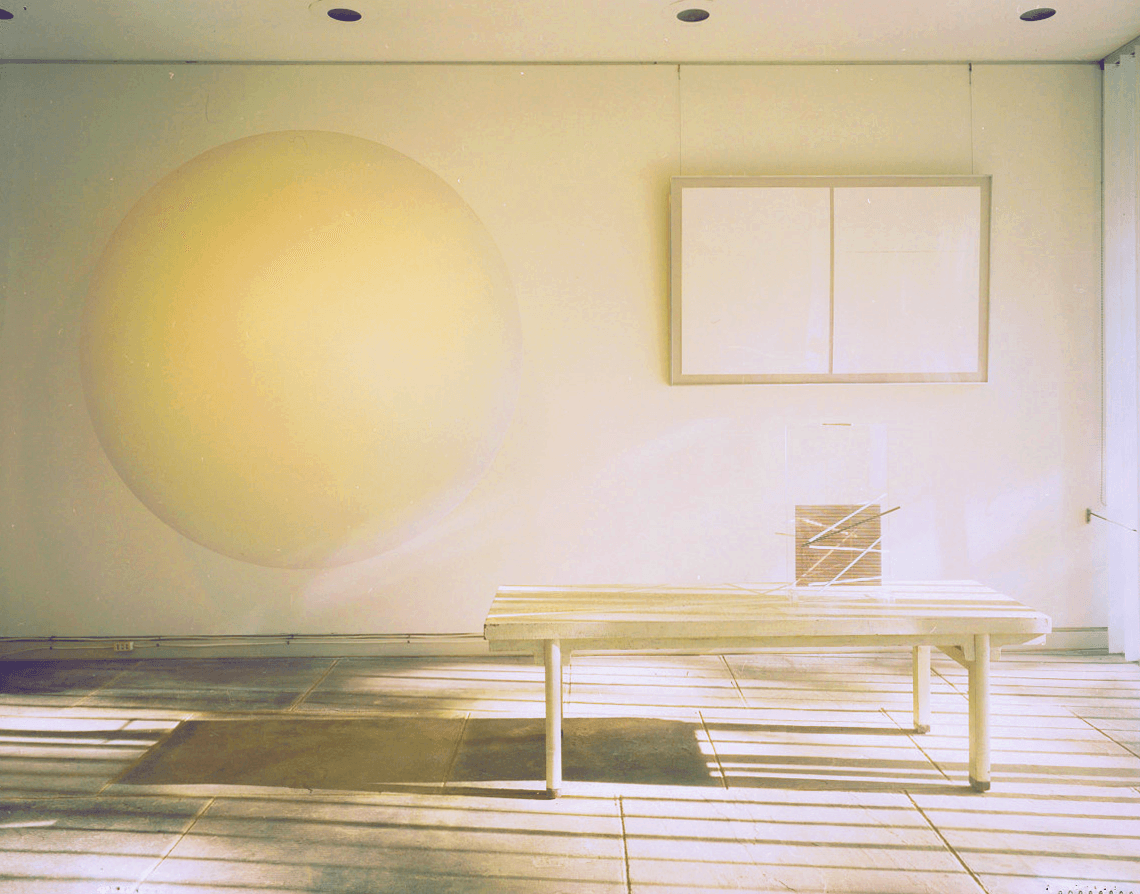

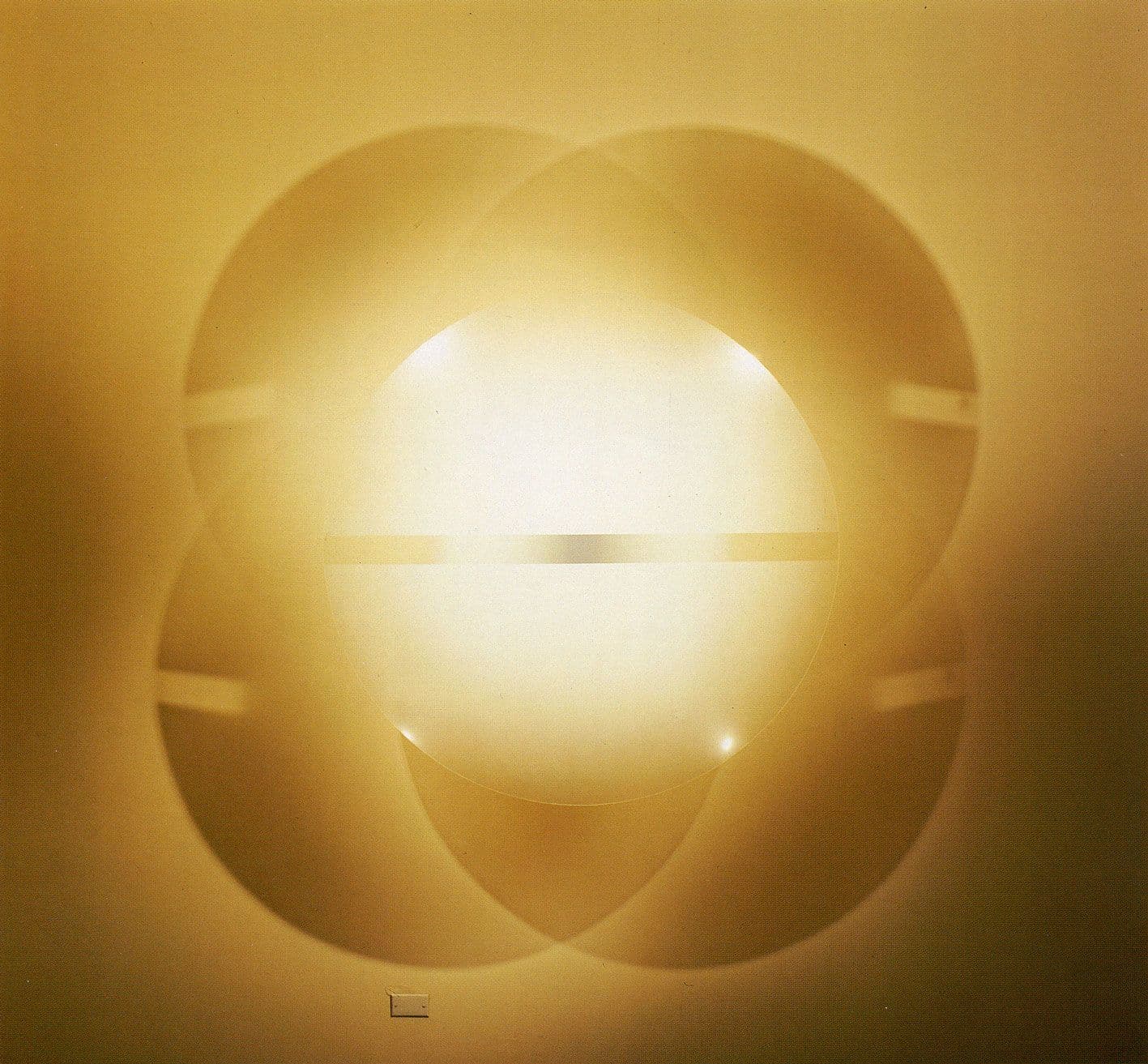

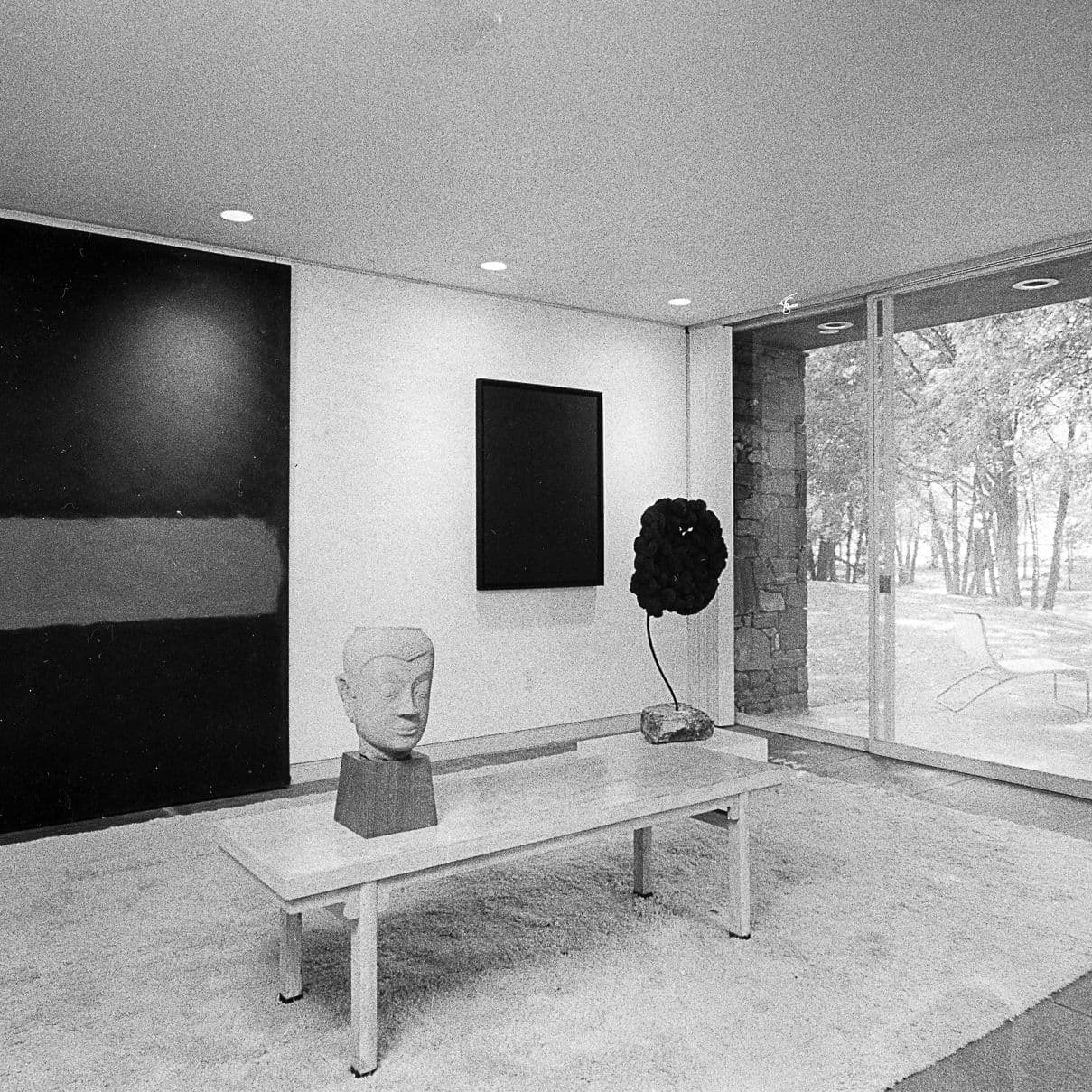

Housley: Okay. That’s going to jump into our next section because she also acquired from you Robert Irwin’s Untitled. And I know that you have said that Irwin changed your life because he pushed the boundaries of what the language is. I am absolutely sure that the Tremaines would have agreed with you completely, because one of the things they did with Untitled, and you probably remember this, is they had this entryway which Philip Johnson had designed for their Madison House, and they rebuilt it so that the disk would be shown to maximum effectiveness. Do you remember that? And do you remember how it came about that Irwin met with them?

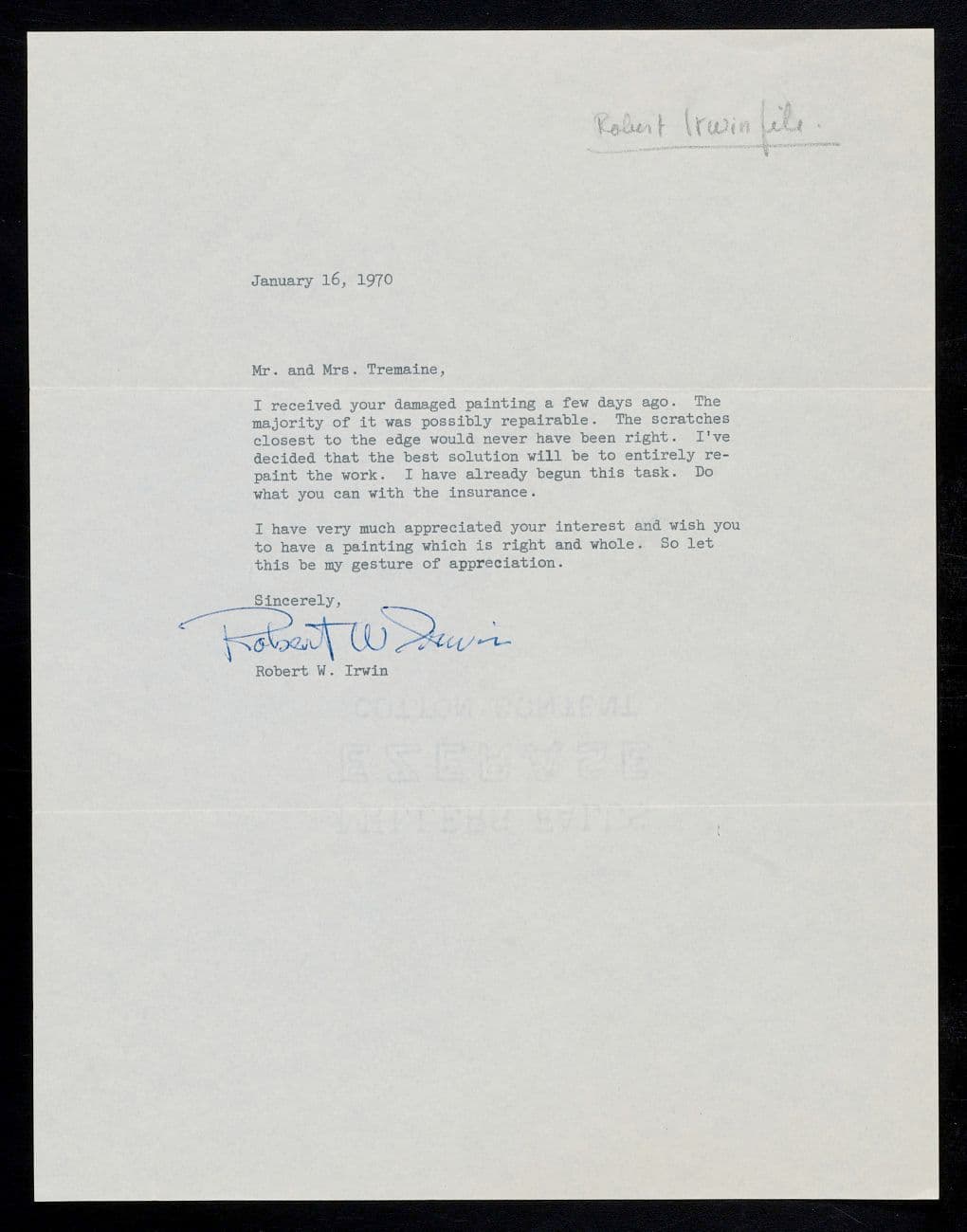

Glimcher: Irwin visited them on a trip from California. Yeah, for me, there’s no artist as radical in the 20th century or any more radical than Irwin—or greater. For me, he’s the greatest, the greatest artist I ever worked with. The greatest mind I’ve ever worked with. And anyway, I don’t remember everything, but the disk was broken.

Housley: No, I didn’t know that.

Glimcher: The disk was broken. So it was rehung in Park Avenue, and our conservators hung it. I mean, I’d do anything for Emily. We didn’t do that for other people. So then the insurance company sued us because it fell off the wall and broke. So the insurance company sued us, and those days, for a lot of money. And we couldn’t settle and we went to court. And Emily and I were sitting together in the front row of the court next to each other. Meanwhile, we should have been antagonists, right? So the judge said at one point, “I don’t quite understand this. Mrs. Tremaine, aren’t you suing Mr. Glimcher, and the two of you seem to be thick as thieves?” Something like that. And she said, “Well, the insurance company is suing Mr. Glimcher. We have a friendship.” And I remember it was just very—there were a few people in the courtroom and everybody laughed. Anyway, that was a tragedy, because it was great.

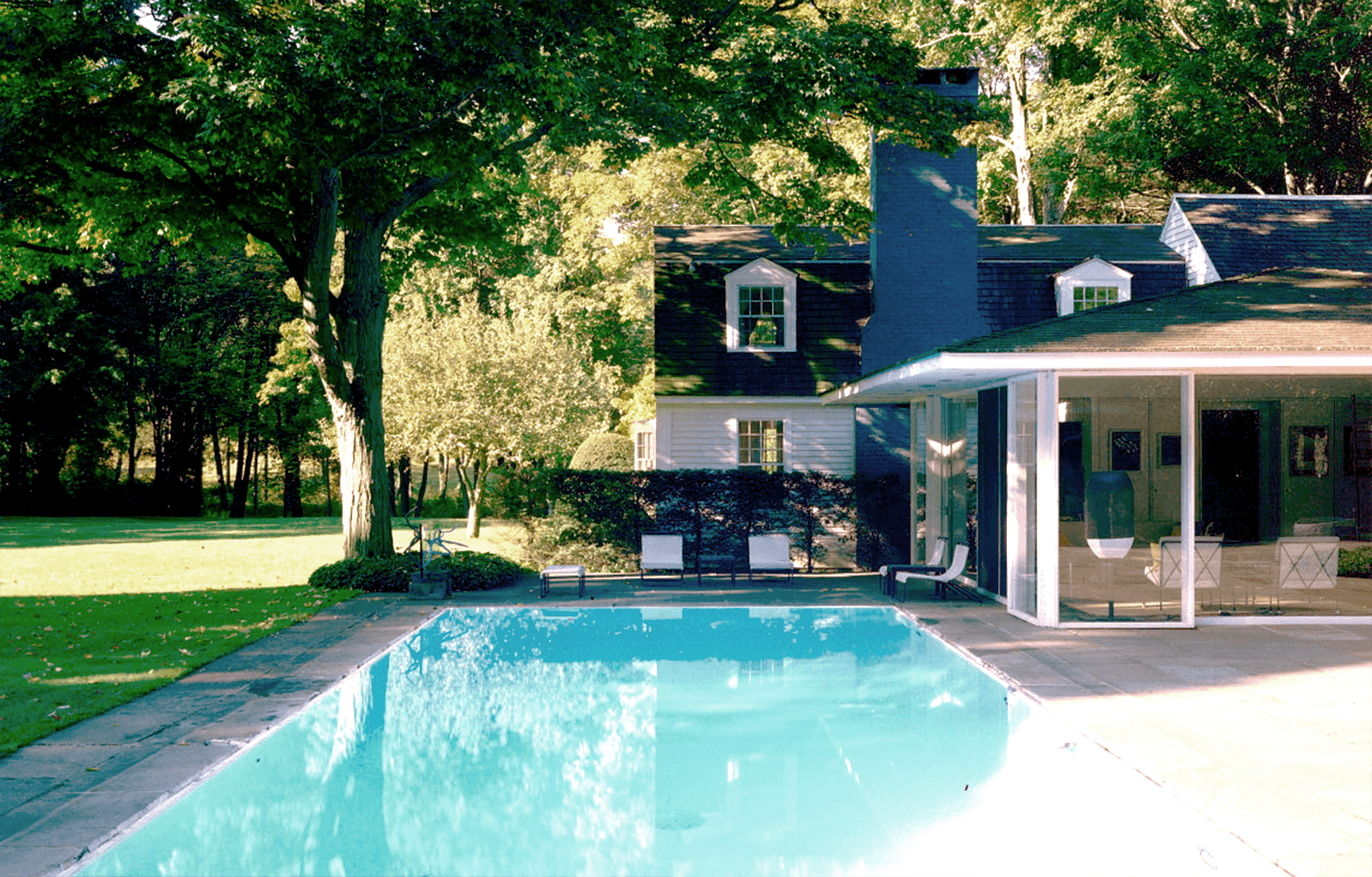

The entry to the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut.

Background image: The Tremaines’ Madison home with Untitled by Robert Irwin, a drawing by Walter De Maria, and a sculpture by Jesus Rafael Soto, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Foreground image: Untitled by Robert Irwin, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, ©1988 Christie’s Images Limited, © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Housley: What about Agnes Martin? Because Emily also acquired the Agnes Martin [Untitled #6] from you.

Glimcher: Yeah.

Housley: And that was the 1980s.

Glimcher: That's the ‘80’s also. But you know, we had very similar taste. So she bought a lot from me because when I got representation of Agnes, which was, again, one of the thrills of my life. Agnes just came in one day and said, “I’m painting again, and will you show my painting?” That was all it was. And I called Emily and she was so excited for me because she also loved the work. And I remember her saying to me, “Well, as soon as you get things you call me.” So that’s how that happened. I mean, there’s so much, I can’t remember everything. It just opens up as we talk.

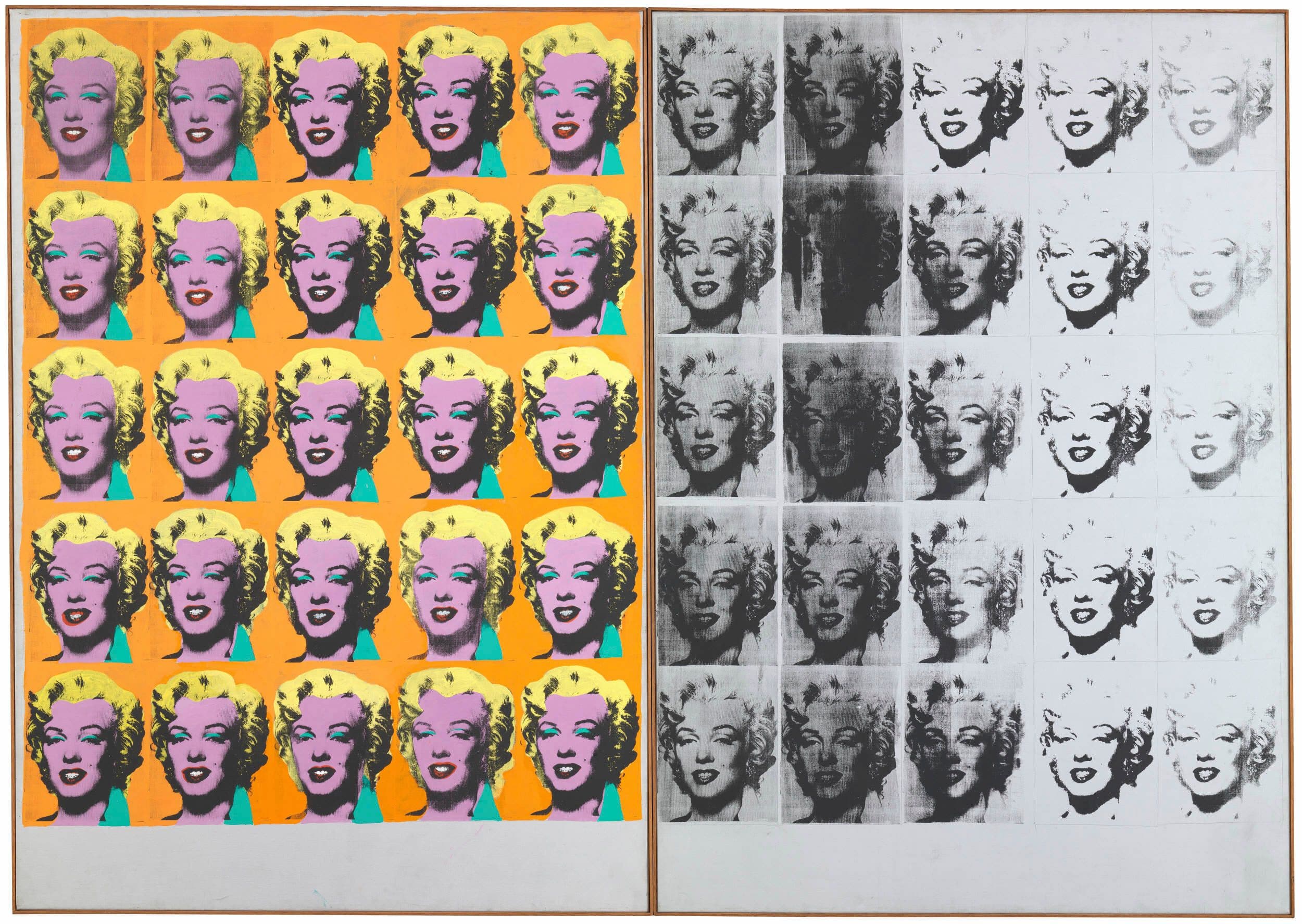

Housley: So we’ve moved through the 1970s, and finally, in July 1980, you handled the Marilyn Monroe Diptych [by Warhol] to the Tate, right?

Glimcher: I did.

Marilyn Monroe Diptych, 1962, Andy Warhol. Tate, Purchased 1980. © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Right Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Housley: Yes. Can you talk a little bit about that? Because that’s a painting that leaves the collection. That’s the first one of any size that leaves the collection. And then, of course, that is going to lead up to Three Flags.

Glimcher: Yeah, we had been talking a lot, and I said to her, “if you want to start placing things, why don’t we do an exhibition and people will see how cohesive this collection is, and we’ll just do an exhibition of this one segment of the collection.”

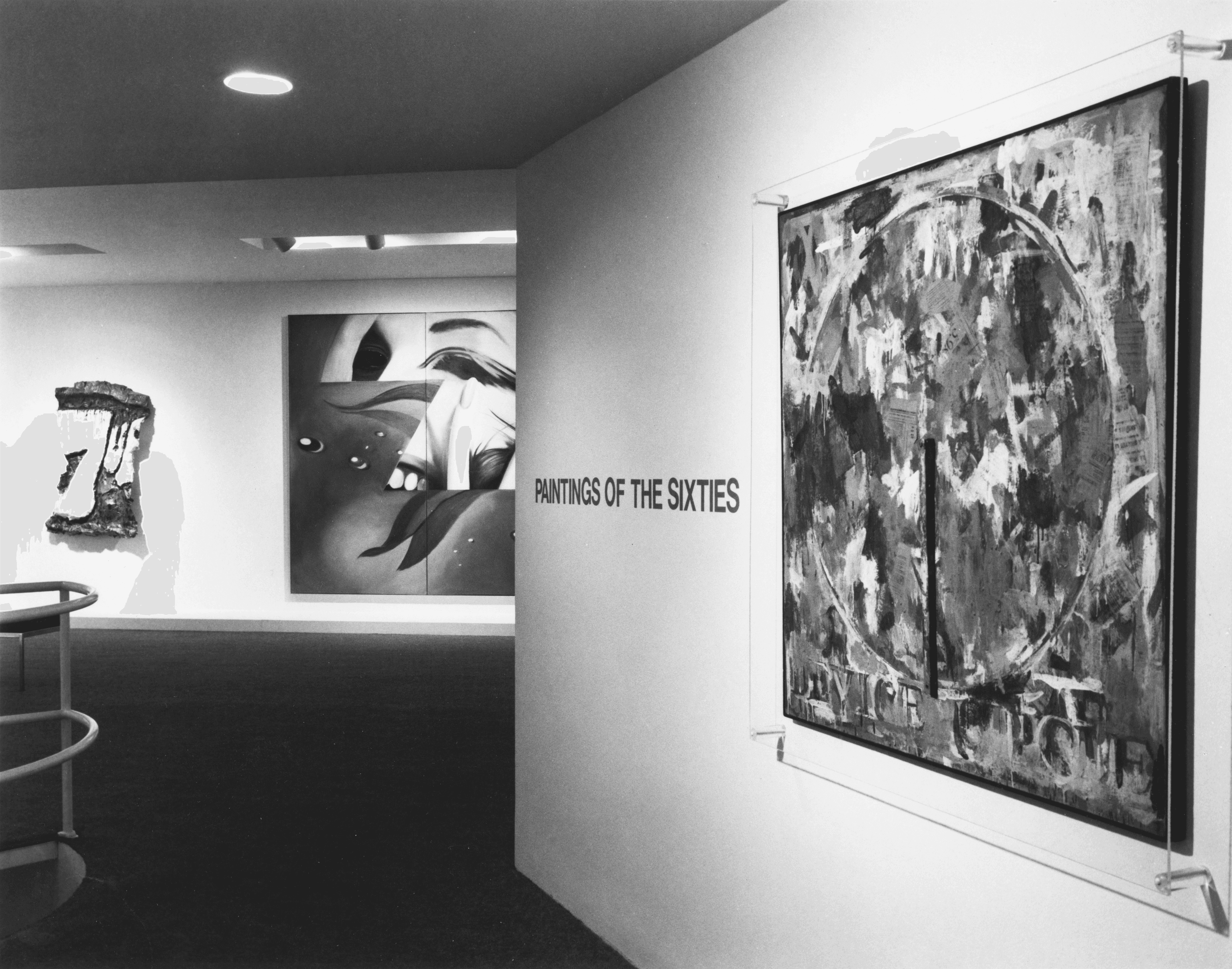

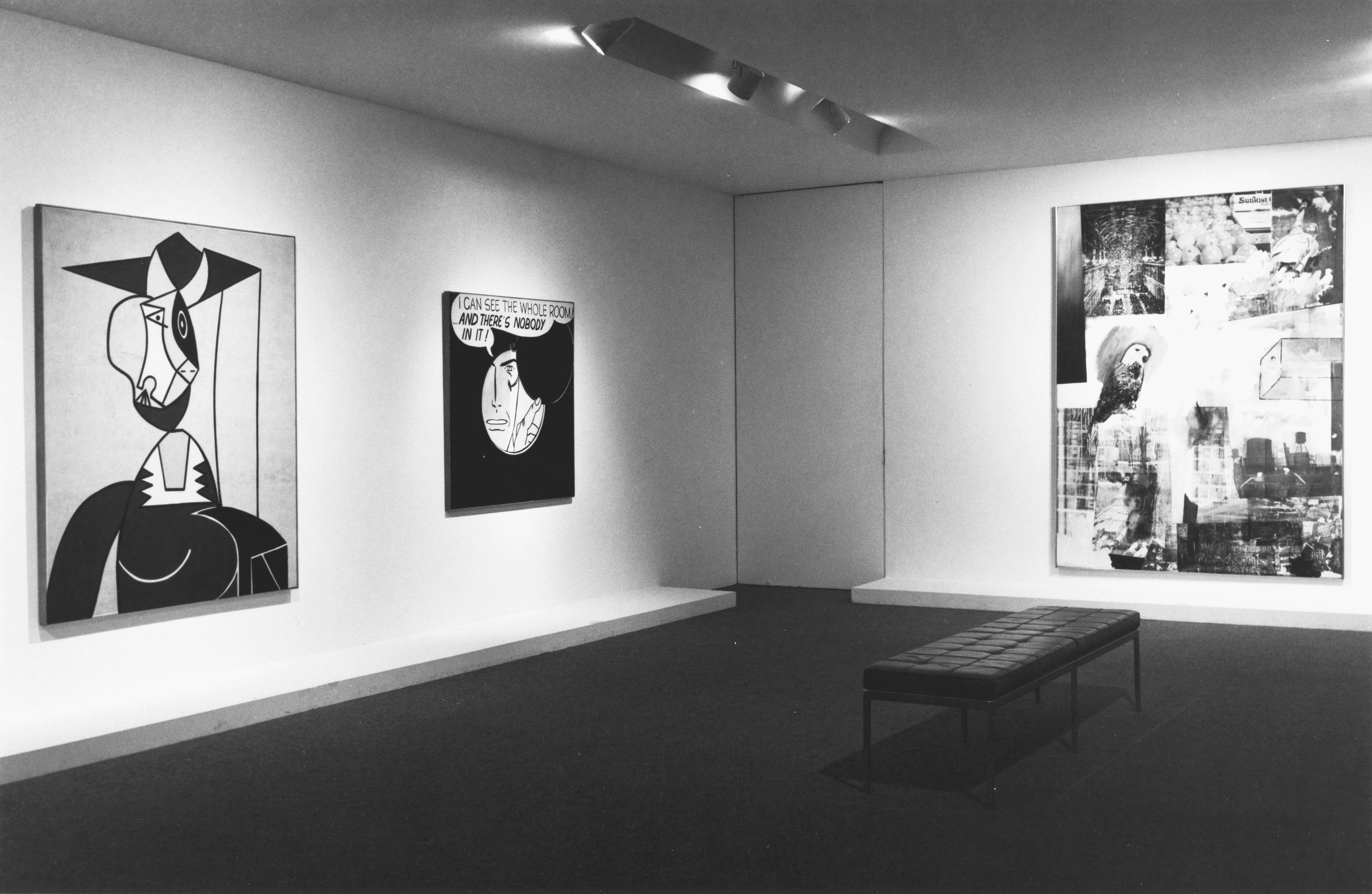

Housley: That was your Paintings of the ‘60s?

Installation views from “Eight Painters of the 60s: Selections from the Tremaine Collection,” The Pace Gallery, 32 East 57 Street, New York, March 28 — April 26, 1980. Artist [From left: Claes Oldenburg, Tom Wesselmann, Jasper Johns]. Photography by Al Mozell, © The Pace Gallery, New York; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Glimcher: Yeah, that was the Paintings of the ‘60s show. And so while we had the show, I was very close to the director of the Tate Gallery then. And he came to the show and sort of said, “It would be great to have all of these paintings. They would make a collection for the Tate that we’re missing.” And I said, “I don’t think the Tate can afford all these paintings, nor do I think the owner would sell them.” And so I said, “What would you like most?” And he said, “Well, the Warhol.” So we sold it for a world record at that point. We sold it for $500,000 for that Warhol.

Housley: Now that surprises me. I had thought it was $270,000.

Glimcher: No, I’m pretty sure it was $500,000. I think the Lichtenstein Picasso was $270,000. And I sold it to the Margulies Collection where it still is.

Installation views from “Eight Painters of the 60s: Selections from the Tremaine Collection,” The Pace Gallery, 32 East 57 Street, New York, March 28 — April 26, 1980. Artist [From left: Roy Lichtenstein, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg]. Photography by Al Mozell, © The Pace Gallery, New York; Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Installation views from Eight Painters of the 60s: Selections from the Tremaine Collection, The Pace Gallery, 32 East 57 Street, New York, March 28 — April 26, 1980. Artist [From left: Andy Warhol, Jim Dine]. Photography by Al Mozell © The Pace Gallery, New York; © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Emily was very pleased that American art could bring that kind of money. And the word got out. You know, you sell to a museum, you can never keep it quiet. There are too many curators and stuff. And the word got out, and it started changing the prices of American art, which would lead up to the Three Flags.”

Housley: And was that the same period of time?

Glimcher: Same period of time, yeah. So we sold those. Yeah, so we sold those two. Emily was very pleased that American art could bring that kind of money. And the word got out. You know, you sell to a museum, you can never keep it quiet. There are too many curators and stuff. And the word got out, and it started changing the prices of American art, which would lead up to the Three Flags. I think we sold the Dine too. The Blue Sky by Dine, did we sell that? I think we did. Anyway, she was very excited about that. And she said, well, look at all this money I have to buy younger artists with. But she never—it was the end of something, not the beginning of something. I think she thought it was the beginning of something. But she was getting older, and she wasn’t so thrilled with the new art that was coming along. She had had the benefit of some of the great art that America produced. And that’s how we got to the Johns, which was in that show. But the stories about the Johns are not accurate. What’s accurate, what I remember, is that Emily had a visit from Peter Ludwig, the Chocolate King. And the Chocolate King wanted that painting. He saw it in my show. And he said to me, “Can I get that painting?” And I said, “I don’t think so. That’s something that Emily really loves. I don’t think she’ll sell that.” I didn’t think she’d ever sell it. So he visited her, and I didn’t know that he visited her. But I was over for a drink on my way home, and she said, “Peter Ludwig offered me $500,000 for the Three Flags and I’m considering taking it.” And I said, “Wow, that is a lot of money. But it’s the quintessential American painting. It can’t go to Germany.” I said, “Don’t you think it has to go to the Whitney Museum?” And she said to me, “They’ll never pay $500,000 for the picture.” And I said, “What if they paid a million?” She laughed. She said that wasn’t possible. I said, “Yes, it is. This is the painting.”

“And I called Leonard Lauder, and Leonard Lauder sent Armstrong over to see the painting. And then, Leonard is one of my closest friends. We’ve been friends for 60 years. And Leonard said to me, “it would put the Whitney on the map if they paid a million dollars for that picture. The world would know about it.” And the Whitney would be thought of more seriously than it was, which is true. It was always sort of the second rate museum. And he said, “What do you think?” And I said, “A million dollars, Emily would really, I think, be tickled at that whole thing.” So I went back to her and said, “Don’t sell it to Ludwig. The painting can go to the Whitney and Leonard will raise a million dollars for it. Can we keep it here at a million dollars? And I’ll take no commission on the sale.” I took nothing on the sale—and just so it was a clean million dollars and not minus a commission or anything. And so Emily said, “Yes.” And then I met with Leonard and we put together four people, each to give $250,000, and that’s how the painting was bought for the Whitney. And it was my idea and I made nothing.”

The Tremaines’ personal black and white slide of Three Flags by Jasper Johns. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

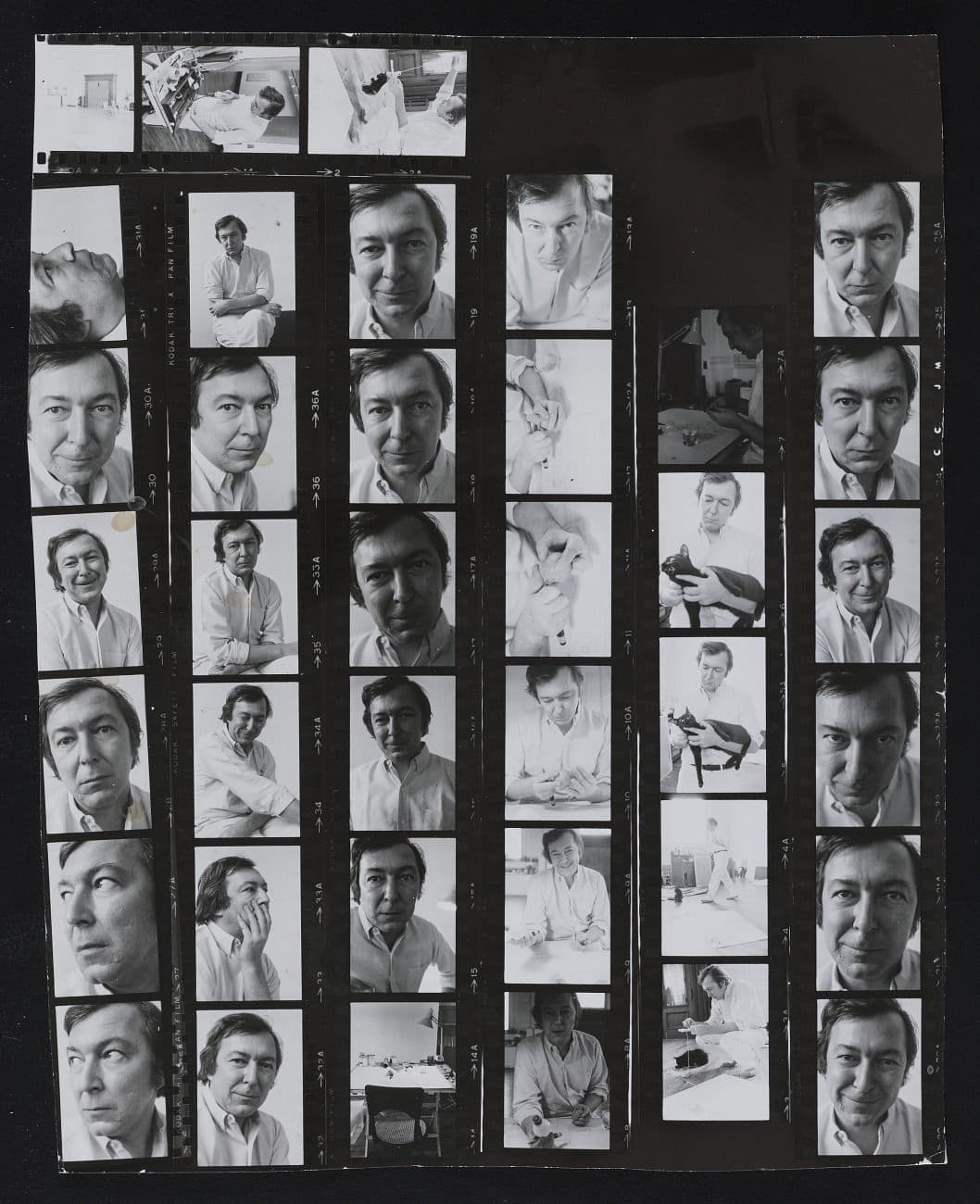

Jasper Johns, circa 1960. Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Housley: In the book that I wrote, you come out very well, and Armstrong was very grateful to you—thankful to you. I mean, really. He felt that the way you handled it, giving them essentially—I think you would use the words at some point a first refusal. But then, also, it was over a three-year payment period. The way it worked out, you were seen as not only pivotal to the sale, but that you handled it extremely well and graciously.

Glimcher: Oh, that’s nice to hear. I had a good time. I had a good time.

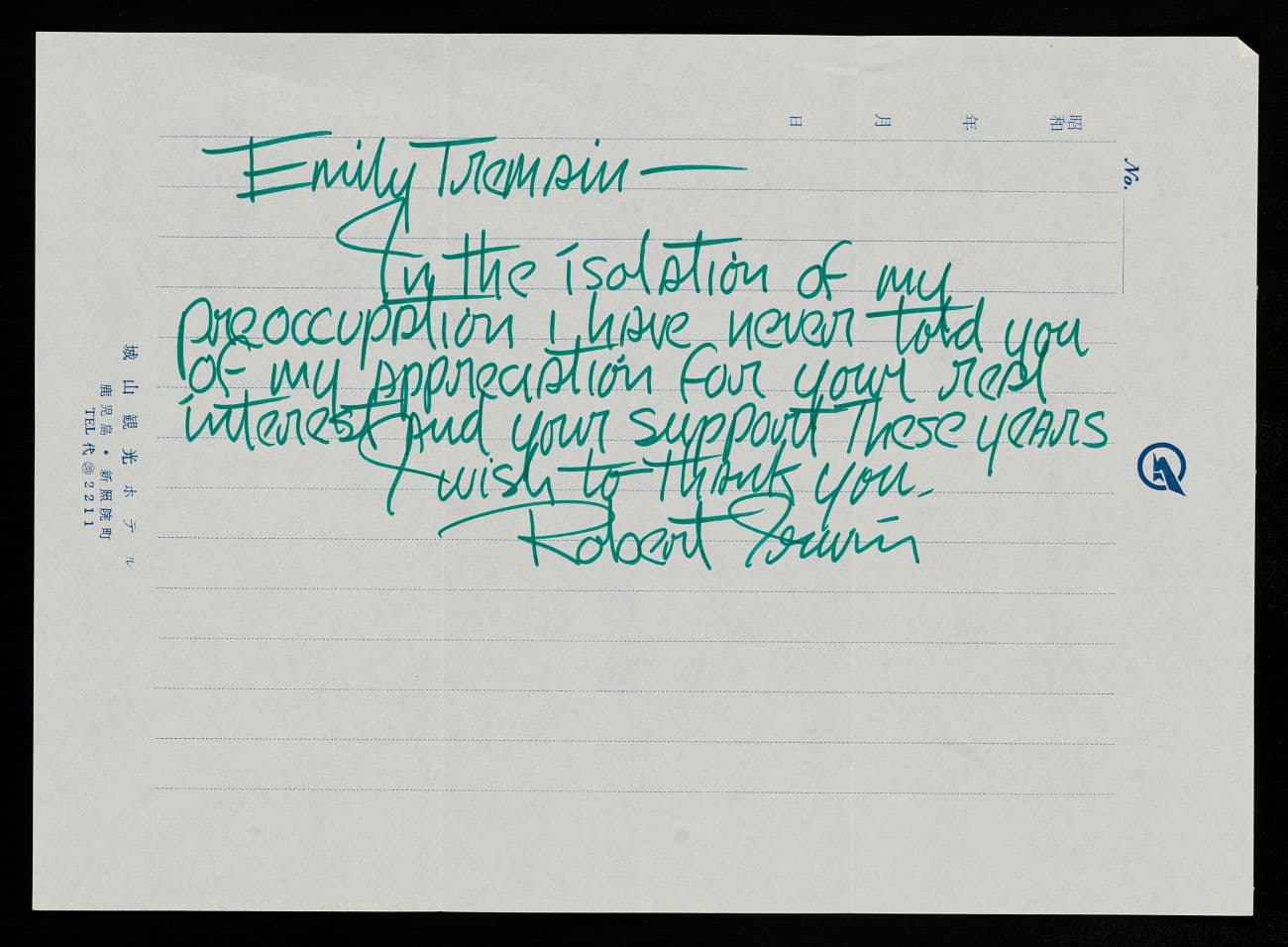

Housley: Well, I also have in the book a letter that Emily wrote to Jasper Johns about a year or so afterwards in which she expresses basically seller’s remorse—that she had wished she had not sold it because it was still her favorite painting. Here’s her letter. You’ll appreciate this: “Dear Jasper, ever since Flag Day, I’ve started several times to write you, but kept postponing until it didn’t make sense anymore. When the Whitney made us that offer, I really did not want to accept it. The picture meant more than that to me, but everyone else seemed to think that by refusing, I was doing everyone—you, the rest of the contemporary painters, the Whitney, even the United States—a disservice. I was still grieving that the National Gallery had not executed their agreement that nothing would be relegated to storage, if not hung at the gallery, then placed in other museums. The Whitney offer implied the picture would be displayed, perhaps even prominently. That was the strongest reason for my decision. Stupidly, I just assumed you would approve of the transaction, and I have always regretted I did not discuss it with you. Burton and I have invested the money and donate the income it produces to social causes. So, in retrospect, it seems that it was a good decision. I was the only loser. I still love the picture as much as I did that first moment in your studio. Emily Hall Tremaine.” That’s a nice story.

Glimcher: It is a lovely letter. So, now I’ll tell you about my letter. Although I made nothing on the painting, it was an honor to deal with it. So, I sent Jasper a case of great vintage Mouton Rothschild Château wine. And so, Jasper wrote me a note—he didn’t write very much—and he said, “Dear Arne, for someone of my generation, a million dollars is an astonishing amount of money. But let’s not forget that it has nothing to do with art.” And he thanked me for the wine. I love that. So, I’m writing my memoirs now. I’m almost finished.

From the Archives

From the Archives

Housley: You have already implied things are going to change the last 10 years of her life. They do still acquire art, I mean like the Agnes Martin is in the 1980s. And there are some other works that they acquire. But there is a sense, as you said, that this was the end of something, not the beginning, although at a certain point Emily was hoping that those sales would be the beginning. So, what was the change, not just in her, I don’t mean just in her, but in the market itself in the '80s that was part of this?

Glimcher: Well, I think it’s more her, frankly. It’s also the market in the ‘80s changed. Suddenly these things have real value. People are very serious about American art. But I think she never got over the fact that she sold those works. I think she regretted it the rest of her life, and she didn’t have the same feeling for acquiring works anymore. She was different. I think the sale of those works was a loss. She didn’t have children and the paintings really became the central focus of her life.

Housley: They were in fact like children.

“Yeah, and she was an iconic class. Coming from her level of society, people didn’t collect avant-garde art. They collected impressionism or they collected Turner. And she just had this—I mean this really—she had the taste of a vulgarian and the elegance of an aristocrat. But you have to have this slight edge. Who buys these Oldenburgs and these strange things that don’t even look like art, and silkscreen paintings? It was just so—nobody else in her level of society collected art like that. She was very special.”

Housley: At the very end of her life—you probably remember Tracy Atkinson, he was with the Wadsworth [Atheneum]—prior to the auction, he had written for the Christie’s catalog what amounted to a benediction for the paintings. He said, “They formed a wonderful ensemble, which will not be seen again. But that is in the nature of things. And indeed, it has been very much in the nature of this collection, which has waxed and waned in both size and scope over the years as new developments came along in the art world. And as the Tremaines traded up towards that extraordinary standard of quality, which they set for themselves from the very first. Now their collection, so carefully and devotedly assembled over so many decades, enters its final transformation. It goes out into the world to new owners to continue the stream of life of the individual works in ever new ways. The Tremaines expected that the collection would thus add to the richness of the world’s cultural life, rather than remaining a static monument fixed in time and space.” Which, as I said, is rather beautiful.

Glimcher: It’s very beautiful. I’d forgotten that. It’s very beautiful. But it just proves how, okay, I’ve great works of art, many of which I still have, some which I don’t. And we’re custodians for a certain period of time, and then they go elsewhere. So, that’s the way it is.

Housley: Can you comment at all about the auctions? [There were two auctions at Christie’s in 1988 and 1991.]

Glimcher: I attended them. But I don’t know. I thought things brought very good prices and they were very respected. The works were considered very important. I don’t know. It was, for me, it was kind of sad. I thought about all the fun we had together, the trips to Connecticut, the times in St. Martin, and it was all gone. It’s just good memories, but that’s the way life is, isn’t it? And we’re blessed if we have those memories. I’ve had a very good time.

The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut where Arne Glimcher and the Tremaines spent time together. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Housley: I can tell. I have only one other question for you, but it’s a little bit off the mark here. You were talking about going up to Madison, and I happen to know that you yourself have a large garden and a sculpture garden.

Glimcher: I do.

Housley: And Emily did too. That was a lot of work to get right. And she had the Gio Pomodoro [Expansion] that was inset into the trees so you couldn’t see the support and the Alexander Liberman [Gyre] and the Jean Arp [Human Lunar Spectral]. And I was wondering, did you ever advise the Tremaines on that? Or were they more of a catalyst for you?

Gio Pomodoro’s Expansion inset into the trees on the Tremaines’ property in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

Glimcher: More of a catalyst for me. Look, we were young when we were going up there and we had very little. The idea of having a house in the country was about as far away as the moon. But I always loved the garden, her garden. And I think it influenced me to become a gardener. I’ve been working in my garden for 40 years now, and it’s one of the great pleasures of my life. So I think Emily influenced that a lot. They were dear friends. They were dear friends.

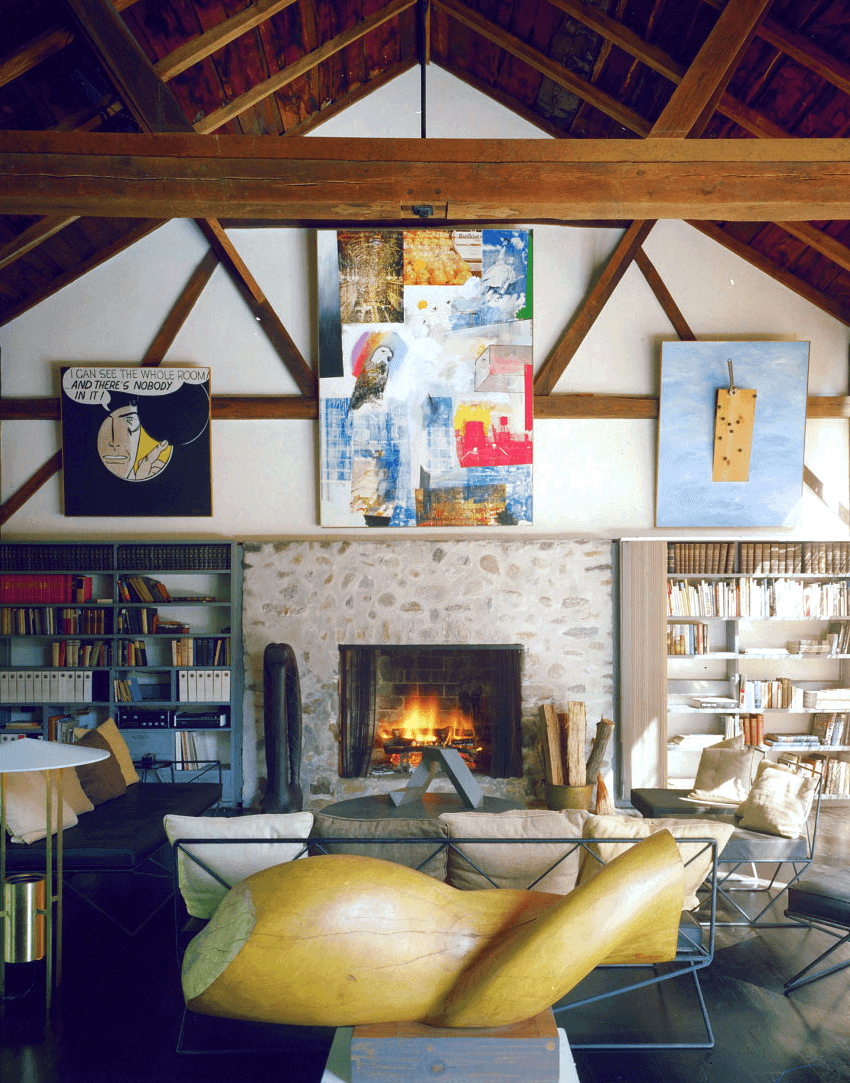

Housley: Yeah. And the way that the inside of the house in Madison flowed to the outside—that was Philip Johnson’s part. But the sculpture, when you were inside, you looked out and saw the Mary Callery [Water Ballet], for example, by the pool and the Arp [Human Lunar Spectral] against the wall. And if you were outside, you looked into the barn and you saw the Rosenberg [Windward] over the fireplace, which was enormous.

Glimcher: Enormous.

Robert Rauschenberg's Windward (center), Raoul Hague's Swamp Pepperwood / © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York in foreground, and Hilary Heron's Girl with Pigtails by fireplace in Tremaine barn at the Madison house, circa 1984. Also pictured are Lichtenstein's I Can See The Whole Room... and There's Nobody in It! to the top left of fireplace, and Cresent Wrench by Jim Dine / Artists Rights Society (ARS) to the top right.

Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Housley: So there was this inflow-outflow, which to me is a little unusual, and it speaks to her perception and the need that things be shown in the best possible way. For example, Irwin’s disk, where they actually redid the room.

Glimcher: She had so much style. I mean, she had style in the way she dressed. She had so much style. And you learn from people like that. I’ve learned. And I learned from Emily. I’ve learned from the other people who’ve been close in my life like that. I grew up in a nice household and everything, but I didn’t know the high levels of glamour that one could live with. And you learn. But she was bad when it came to food. The cuisine was not good at the Tremaines. It was sustainable.

Housley: Well, they had a French chef for a little while, and people have remarked that that was the high point, the culinary high point.

Glimcher: I did not have the benefit of that French chef. Anyway, they were terrific, and I love them, and they’re a great memory.

Housley: I have reached the end of my questions for you.

Glimcher: I have reached the end of my answers.

Housley: Well, it’s a lovely place to stop.

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: Arne Glimcher. Photo courtesy of Kevin Sturman, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.