Story

More Than the Sum of Its Parts:

Louise Nevelson and Emily Hall Tremaine

Louise Nevelson’s austere black sculpture—like the ruins of an ancient city at night—presented Emily Hall Tremaine with a challenge as an art collector: how to display individual pieces that had been created as components of a much larger all-encompassing environment in which visual power was accumulative. Realizing that Nevelson’s exhibition Moon Garden + One in 1958 was a gestalt in which the whole was more than the sum of its parts, Tremaine wanted to make sure the separate parts did not lose power once they stood alone.

This challenge was made more difficult because there was a reverential otherworldly quality to Nevelson’s sculpture. Some critics had interpreted the interior space in her work as a boxed-up hollowness. But to Nevelson, and also to Tremaine, the hollow was also hallowed—a tenebrous sacredness. The art historian Elyse Deeb Speaks wrote that, “Without behaving precisely like a crypt or even a chapel, Nevelson’s environments summoned up the experience one would expect to have in such a place.”

Tremaine first became aware of Nevelson’s art in the 1940s because of her numerous shows at the Nierendorf Gallery that Tremaine frequented and from which she purchased the painting The Departure of the Ghost by Paul Klee. Karl Nierendorf was one of the most unique gallery owners in New York having emigrated under duress from Berlin, Germany in 1936. There he had run a gallery that showed contemporary art deemed to be degenerate by the Nazis. Nierendorf had an aesthetic openness that spanned the whole world. Most unusual, he was open to women artists, providing encouragement and support.

“I found lumber in the streets that had nails in it and some nail holes in it and different forms and different shapes. And I just nailed them together. And I knew this was odd.”

Already Nevelson was using detritus including scraps of wood, splintered orange crates, jagged railings—whatever she could find on the backstreets of New York. She began by painting them black as a means of unification and then reassembling them. These were not sculptures chiseled from stone, formed from clay, or hammered from hot metal. The process was more like carpentry with the wood nailed together in ways that had no reference to its former purpose—a splintered piano leg upholding a visual universe instead of a musical one.

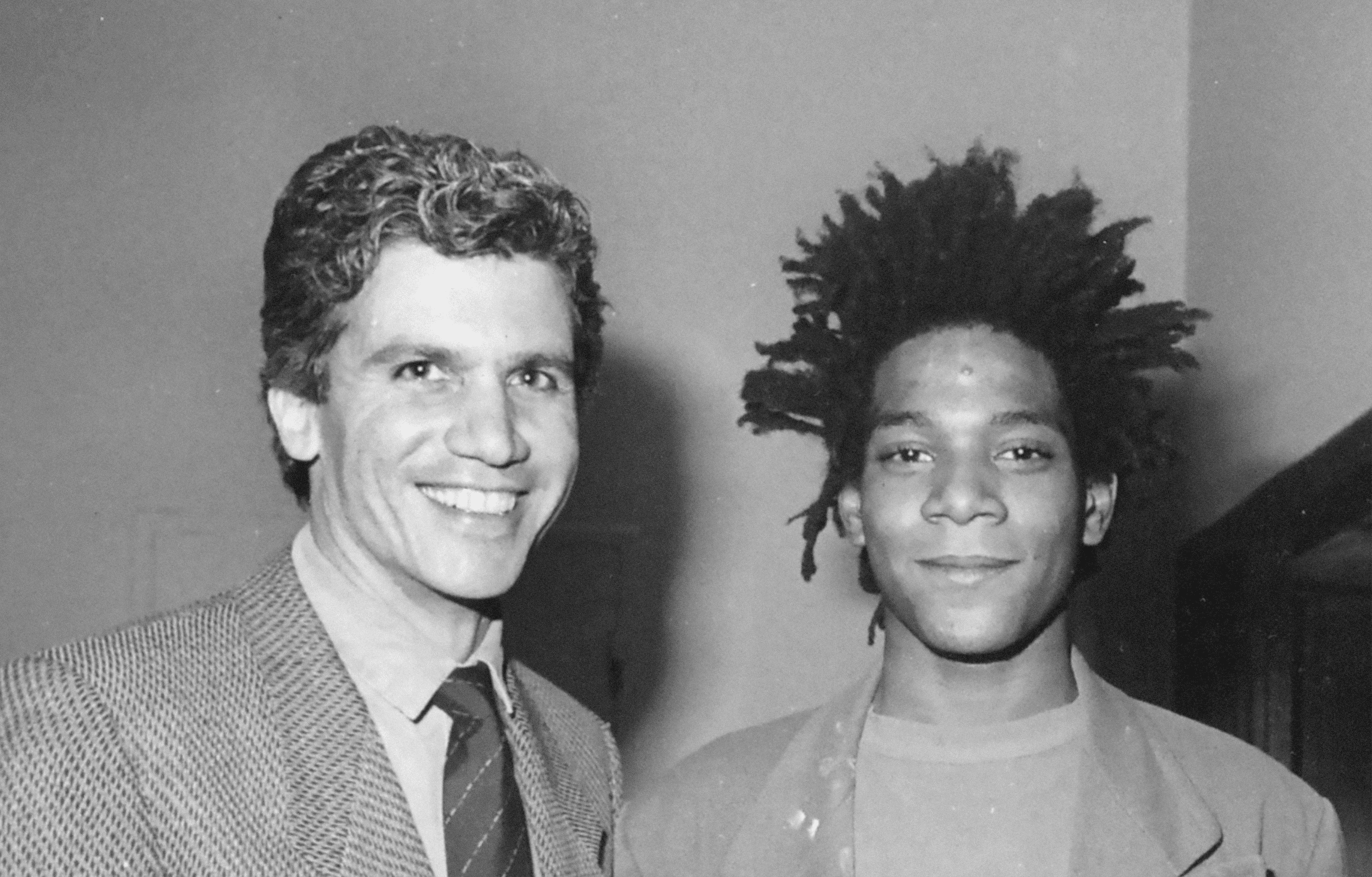

Louise Nevelson in her studio.

Background: Louise Nevelson in her studio. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Foreground: Louise Nevelson – ‘New York is My Mirror.’ Courtesy of Tate © Tate, 2024.

It was not until Nevelson’s 1958 exhibition Moon Garden + One at Grand Central Moderns Gallery in New York City that Tremaine turned her sharp eye in Nevelson’s direction. By then Nevelson was 59 years old and had been fighting every minute of her adult life for recognition. For her, that exhibition was not so much a breakthrough as a testimony to her perseverance.

Perhaps Nevelson’s perseverance was one of the reasons why the exhibition was as much about art as an environment as it was about a single work. Nearly every square inch of gallery space was used with constructions stacked on top of each other, extending from the walls into the center of the gallery. Visitors had to work their way around the constructions, which was disconcerting because Nevelson played with scale, from a work so small it could sit in the palm of a hand to “Sky Cathedral,” an overwhelming eleven feet in height rising up from floor to ceiling.

From the Archives

From the Archives

To heighten the spell of a garden in moonlight, the gallery windows were covered up and the space was illuminated by dim blue lights. The term “happening” was not widely used yet, but the show came close to being one of the first because there was a performance aspect to it involving visitors, among them the Tremaines, who had to squeeze through, trying to avoid bumping into the works and each other. People were part of the art environment—a “being there” loosely connected to phenomenology and conscious experience.

Arnold Glimcher, who was a friend of both Nevelson and Tremaine, described the exhibition as installation art, the first in the nation. But installation art, as it came to be defined, has a temporary aspect. That was not the case with Moon Garden + One. Nevelson expected the exhibition as a whole to be temporary but the individual pieces to be permanent. She also expected them to stand on their own.

Critical reviews of Moon Garden + One were mostly positive, but only seven works sold of which the Tremaines purchased three, two from the gallery and the third directly from Nevelson. The art critic Hilton Kramer wrote in the New York Times that during the 1950s few collectors were interested in modern sculpture. “It was painting that was assumed to represent the mainstream of creative endeavor. Those interested in new sculpture, especially abstract sculpture, thus constitute a minority within a minority.”

Louise Nevelson, Moon Garden Series, c. 1957. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian. Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Louise Nevelson, Moon Garden Series, c. 1957, with figures out of the boxes. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The smallest of the Moon Garden Series purchased by Tremaine has three hinged boxes, or more exactly chests, each holding tiny figures that feel like ancient cultic amulets, as if they had come from a Mesoamerican archeological site. Rough-hewn, they can only be seen completely by removing them from the boxes.

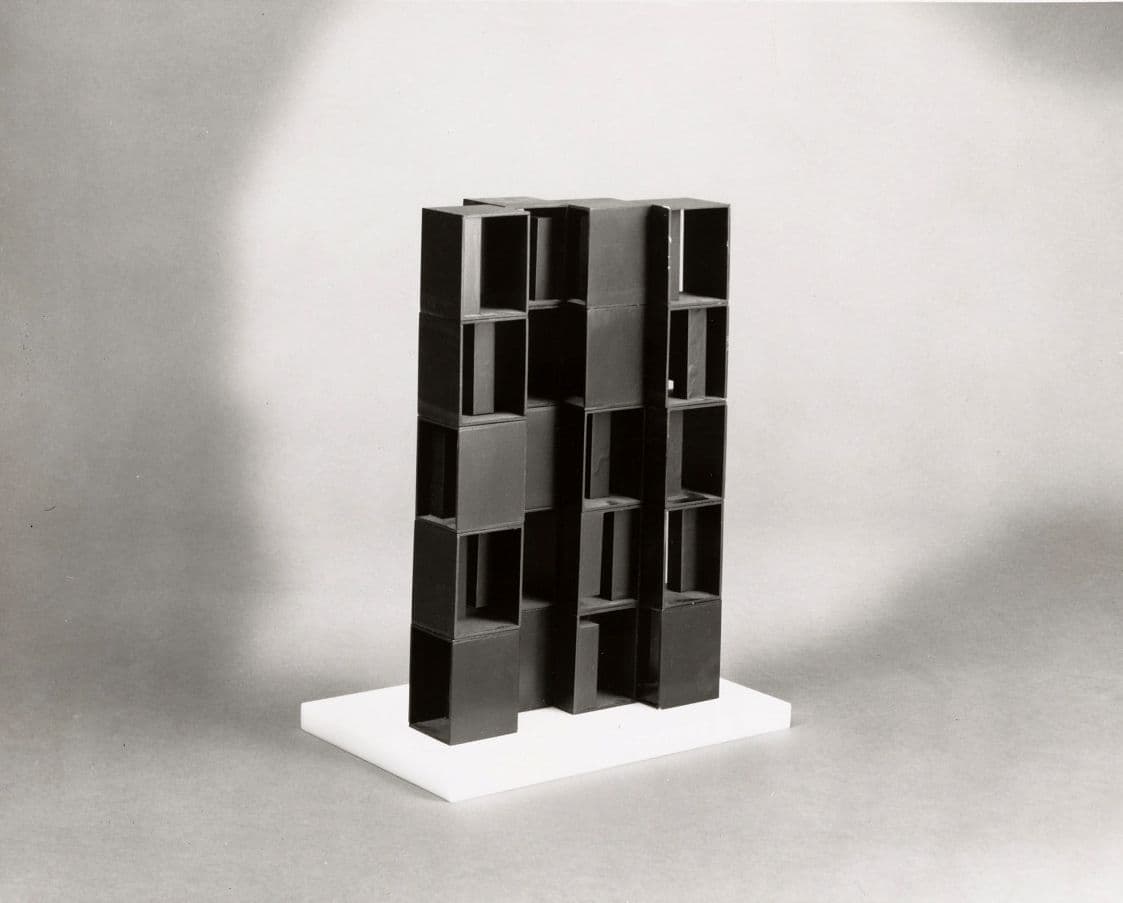

Louise Nevelson, c. 1957. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The second work with the same name also has three boxes that are not hinged and are vertical. When the three boxes are stacked, it is approximately three feet in height, although Tremaine chose to set the boxes beside each other. Splinters of wood in two of the boxes are in contrast to a half circle and a smooth curvilinear shape in the third box, which is slightly taller and has a base.

The third, Moon Garden Reflections—also titled Mourning Becomes Electra after the play by Eugene O’Neill—is the largest at 76 ½ x 30 x 10 inches.

Gregory Hedberg, curator at the Wadsworth Atheneum at the time of the Tremaine exhibition, wrote in The Tremaine Collection: 20th Century Masters, “Within the simple framework of three boxes of nearly equal dimensions, all black and all made of wood, Nevelson placed a variety of complex objects that are both revealed, and concealed by the boxes…The overall mood created by these boxes is somewhat sinister and mysterious, almost gothic, indeed the varied objects themselves have been seen as suggesting the macabre instruments of a black mass.”

After the exhibition closed, Emily and Burton Tremaine along with their friend the architect and fellow collector Philip Johnson, visited Nevelson’s studio to view new work. It was Tremaine’s habit to visit art studios because she believed that it was only there she could see the art “coming through” the artist. Nevelson’s studio was also her home, but it was so chock-full of sculpture it was hard to imagine how she lived there. Hilton Kramer wrote that everywhere was a “pell-mell profusion of forms, its architectural divisions of space and its twilight atmosphere.”

Preceding Image: Louise Nevelson, Moon Garden Reflections, 1956. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Louise Nevelson, model of Atmosphere and Environment II, black lucite. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Tremaine also purchased a model of a larger sculpture on which Nevelson was working titled Atmosphere and Environment II. She wrote to Nevelson, “I am very excited to see what you create to support the Greek columns(it always makes me think a little of “Mourning Becomes Electra”). Philip Johnson, my husband, and I all love it, but we also love the pieces that give us a sense of the mystic emotionalism of the Gothic spirit. The macabre playfulness with grotesque angles, high vaulted shadows, nails, etc. I seem to remember the two original supporting boxes were in this mood, but none of us can quite remember them in detail. However, we all feel that each piece you do surpasses its predecessor so we are not worried.”

Part of the Tremaines collections of miniatures, including a piece by Louise Nevelson (middle row on the right), on display in their New York City apartment, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

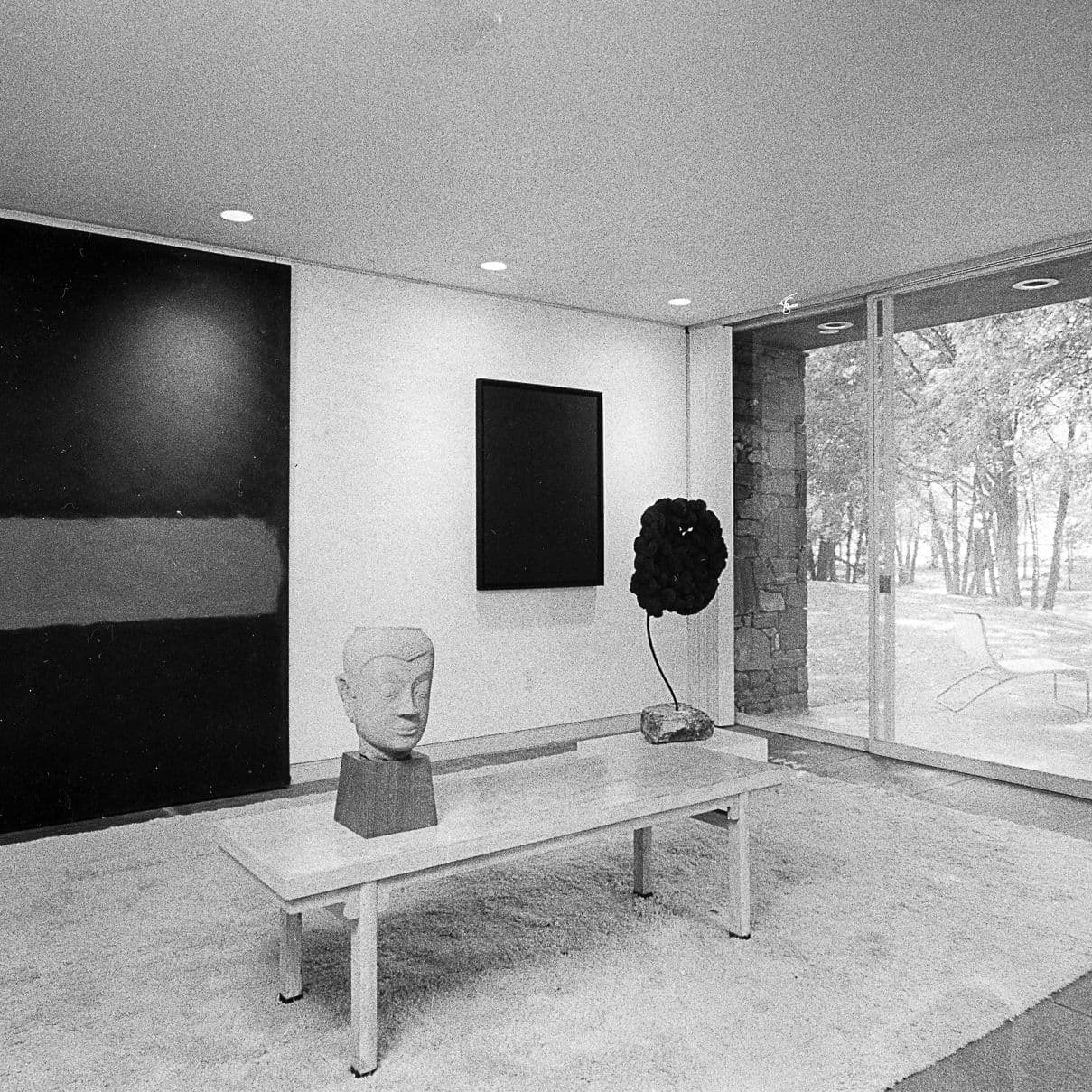

Tremaine often placed artworks together in harmonic ways to create intriguing juxtapositions. And so she hung one of the Moon Garden Series on the wall with her miniature collection as if it were a painting instead of a sculpture. Above it was Ad Reinhardt’s monochromatic Blue Composition, which also required up-close looking. Next to it were Motherwell’s austere Spanish Elegy Number 17 and Pollock’s reserved Silver and Black. Moon Garden was in somber—and very small—company. Even so, it was no longer a part of a vast silent necropolis but was more like a trinket picked up by an archeologist and displayed with other curios.

At over six feet in height, Moon Garden Reflections was placed against a wall in Tremaine’s country home in Connecticut. Nevelson once wrote that her “total conscious search in life” included not only the object but “the in-between place.” The in-between also pertained to Tremaine’s decisions on Moon Garden—not a resting point but a place of passage—a portal to a beautiful nether world.

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover Image: Jeremiah Russell. Portrait of Louise Nevelson, ca. 1955. Louise Nevelson papers, circa 1903-1982. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: Art, Environment, and Learning Differences.