Story

The Sculpture Garden:

Raising a Crop of Difficult Beauty

Picture a private sculpture garden in late winter with nobody around. The cool New England light falls on a sinuous piece of bronze, eleven feet long, artfully positioned in an evergreen hedge. The rough green needles provide contrast to the smooth gray metal and hide the structural supports creating the illusion that the sculpture floats. Titled Expansion, the sculptor Gio Pomodoro wished it to play with light. And it does.

Gio Pomodoro’s Expansion on the Tremaines’ property in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

In front of another hedge is a bronze titled Family Going for a Walk by the British sculptor Kenneth Armitage. The figures lean into the wind that keens around the corner of the eighteenth-century farmhouse, now empty, its owners having gone to New York City or perhaps Europe where they are probably at this very moment visiting an artist’s studio or a museum.

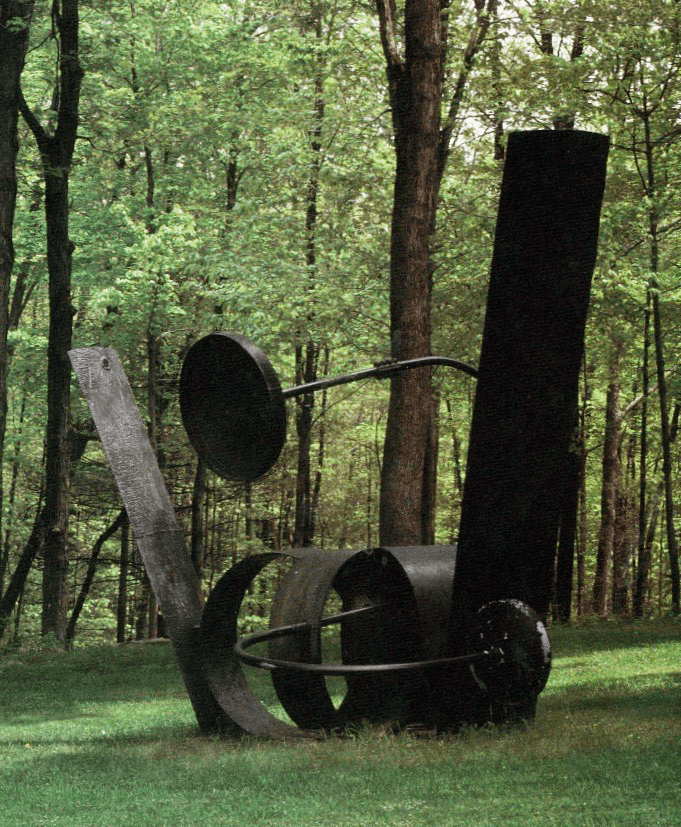

Alexander Liberman’s Gyre on the Tremaines’ property in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

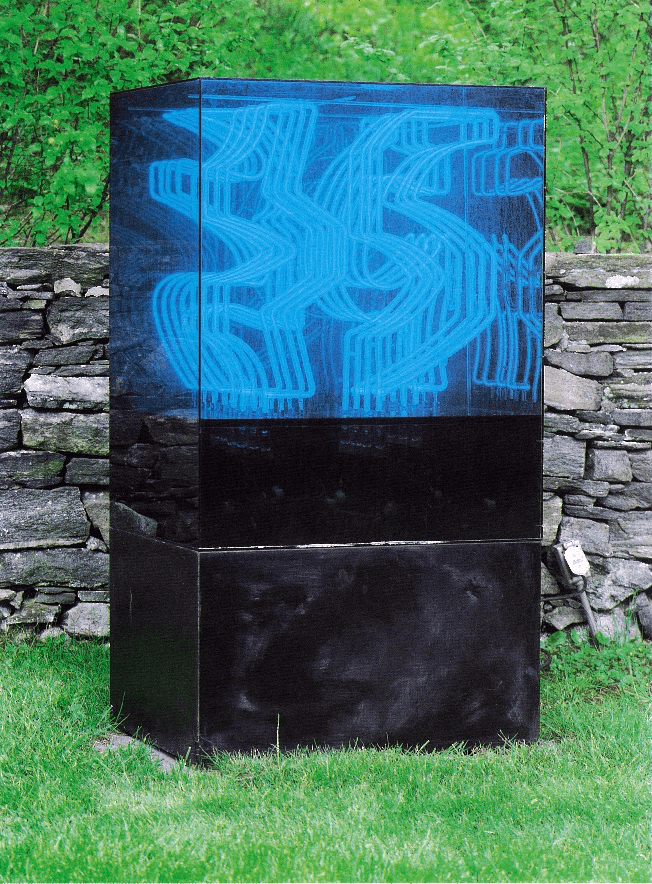

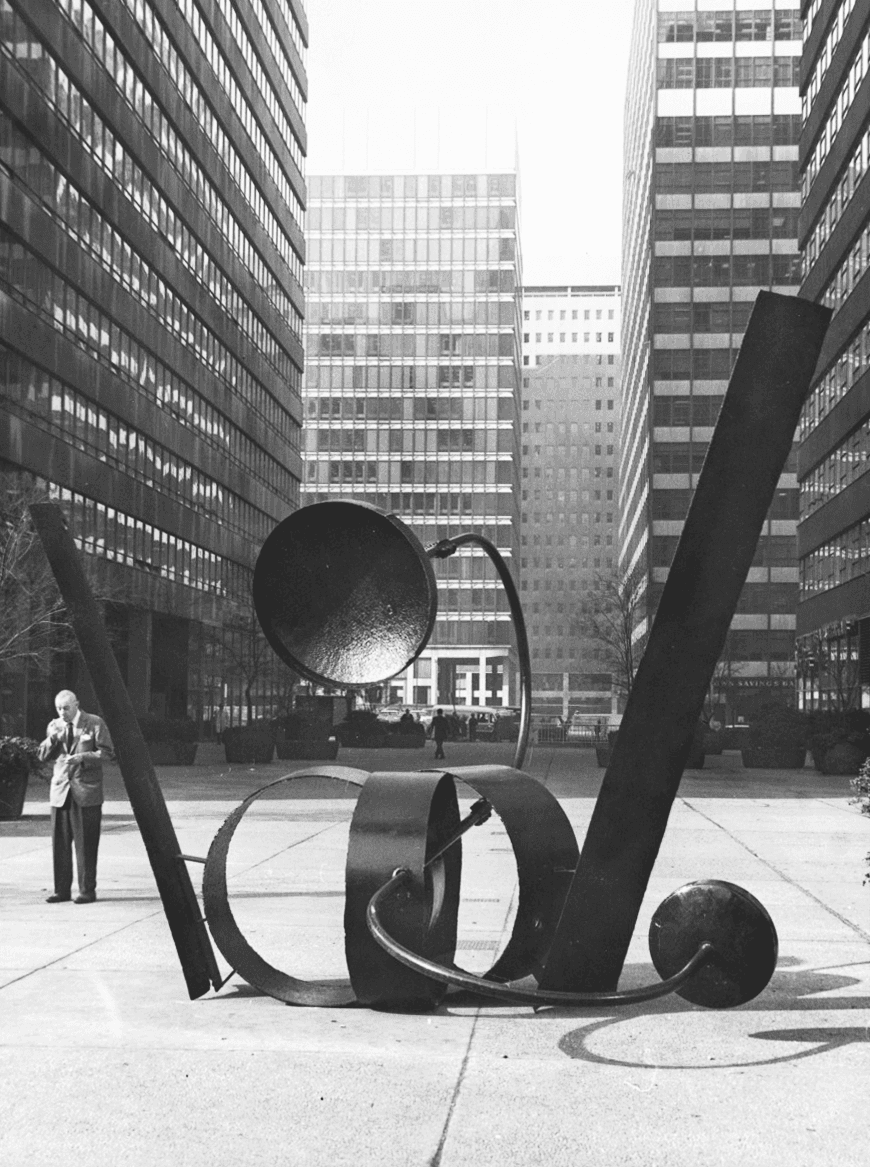

Inside the house and barn are many paintings that the owners often loan for major art exhibitions. However, they can’t loan the sculptures that, to be moved, need cranes and forklifts, trucks and careful workers. Some of the sculptures also require more space than any but the largest museums can provide, for example, the black one titled Gyre by Alexander Liberman, which curves in all directions on the lawn taking up twelve feet by eight feet by ten feet of space.

I think I’m a magpie to start with, and I’ve always collected since I was able to pick up objects…

And so, the sculptures stay put, awaiting the arrival of spring when people will return, parties will be held once again in the barn, and visitors will wander the grounds, entranced to find at the far end of the property a sculpture titled Arch Brown by John Chamberlain made of crushed auto parts, its enameled colors bright against the gray outcropping on which it rests.

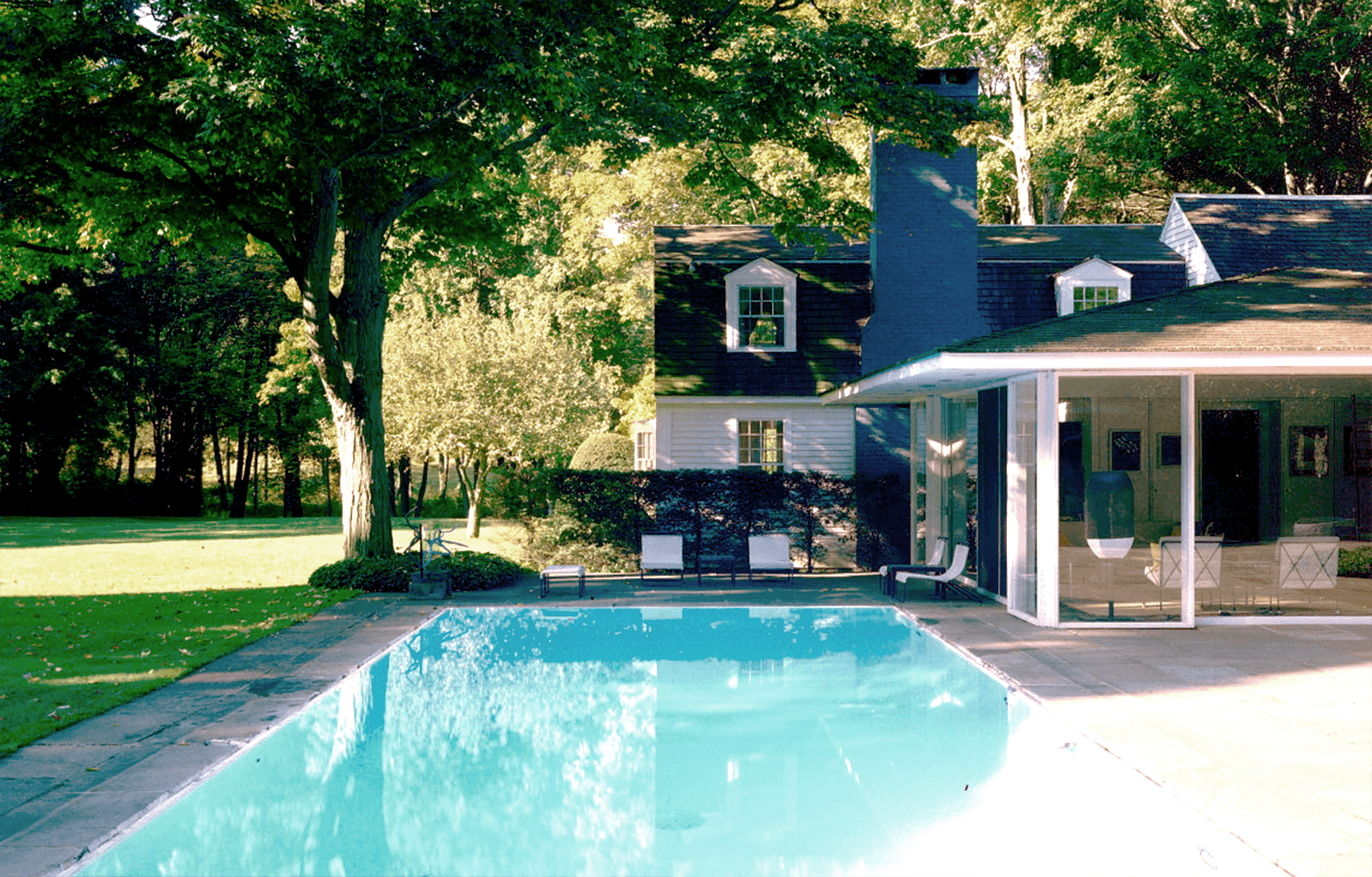

The sculpture garden in the above scenario belonged to Burton and Emily Tremaine and was located in rural Madison, Connecticut. Burton had purchased the property before his marriage to Emily in 1945. It consisted of a colonial house, outbuildings, and an old barn that had been renovated with stone fireplaces at both ends. Dark and drafty, the barn was unsuited for art. As a result, the Tremaines began to make changes to accommodate their growing collection including sculpture, which demanded not just space, but the right space.

John Chamberlain’s Arch Brown on the Tremaines’ property in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

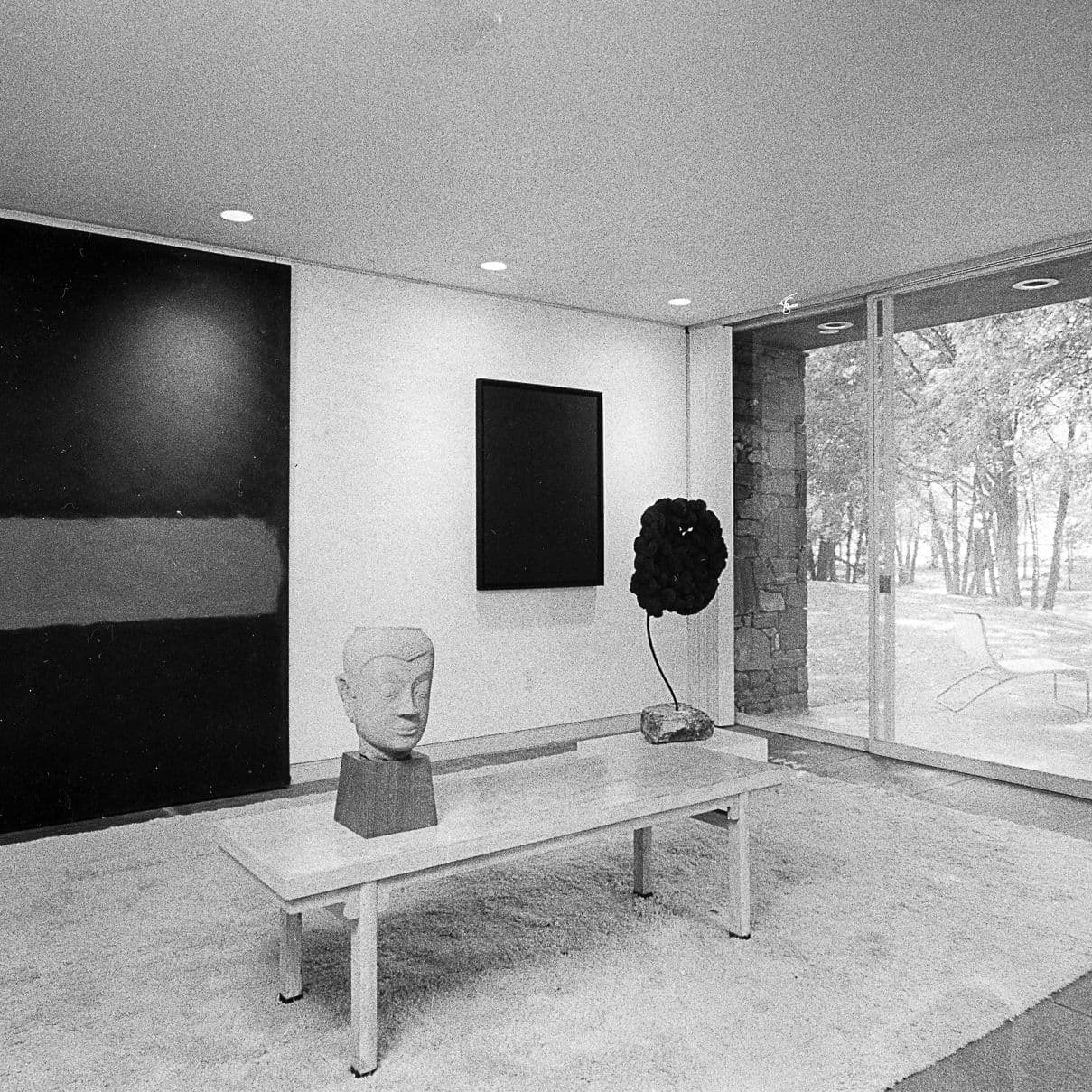

Their partner was the architect Philip Johnson who had recently designed his Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. Sometimes he was hired outright, but at other times he simply made suggestions. In a speech at the opening of the Tremaine exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1984, Johnson said, “All I remember is we’d sit around in the evening and they’d say, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we had a swimming pool here or a place to put pictures over there, or this living room is really awfully small, isn’t it?’ And so the pleasantest days an architect can spend are with friends, are with people who are sympathetic to your ideas.”1

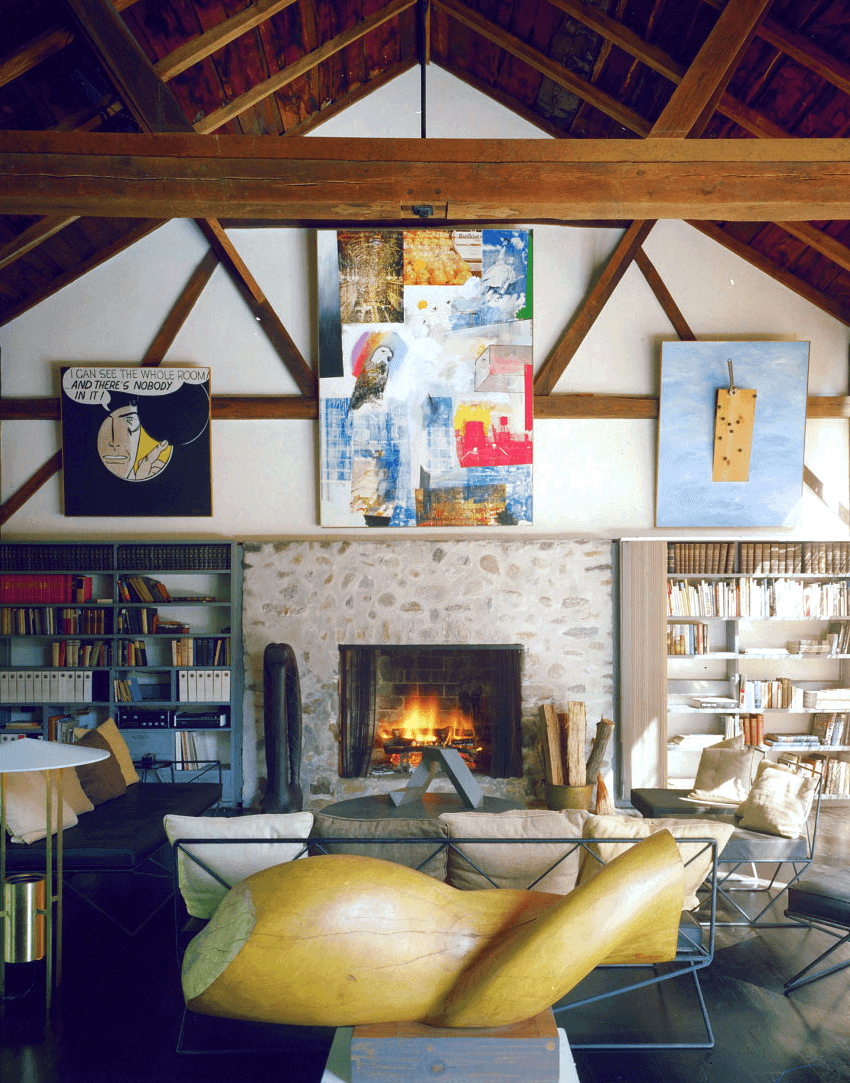

As he had done with his own house, Johnson used glass to open up the barn filling it with light. He reduced the size of one of the fireplaces to create more space, leaving the rough-hewn siding and wooden beams. He also added to the house a large glass room with a bluestone floor contiguous with the outside terrace. More of an outdoors person than Emily, Burton loved the place. Each year when autumn came, he wanted to stay instead of returning to New York.

1—For information on the renovations, see Volker M. Welter, Tremaine Houses: One Family’s Patronage of Domestic Architecture in Midcentury America (2019), The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

The barn at the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut.

Background: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Foreground: The barn's interior courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

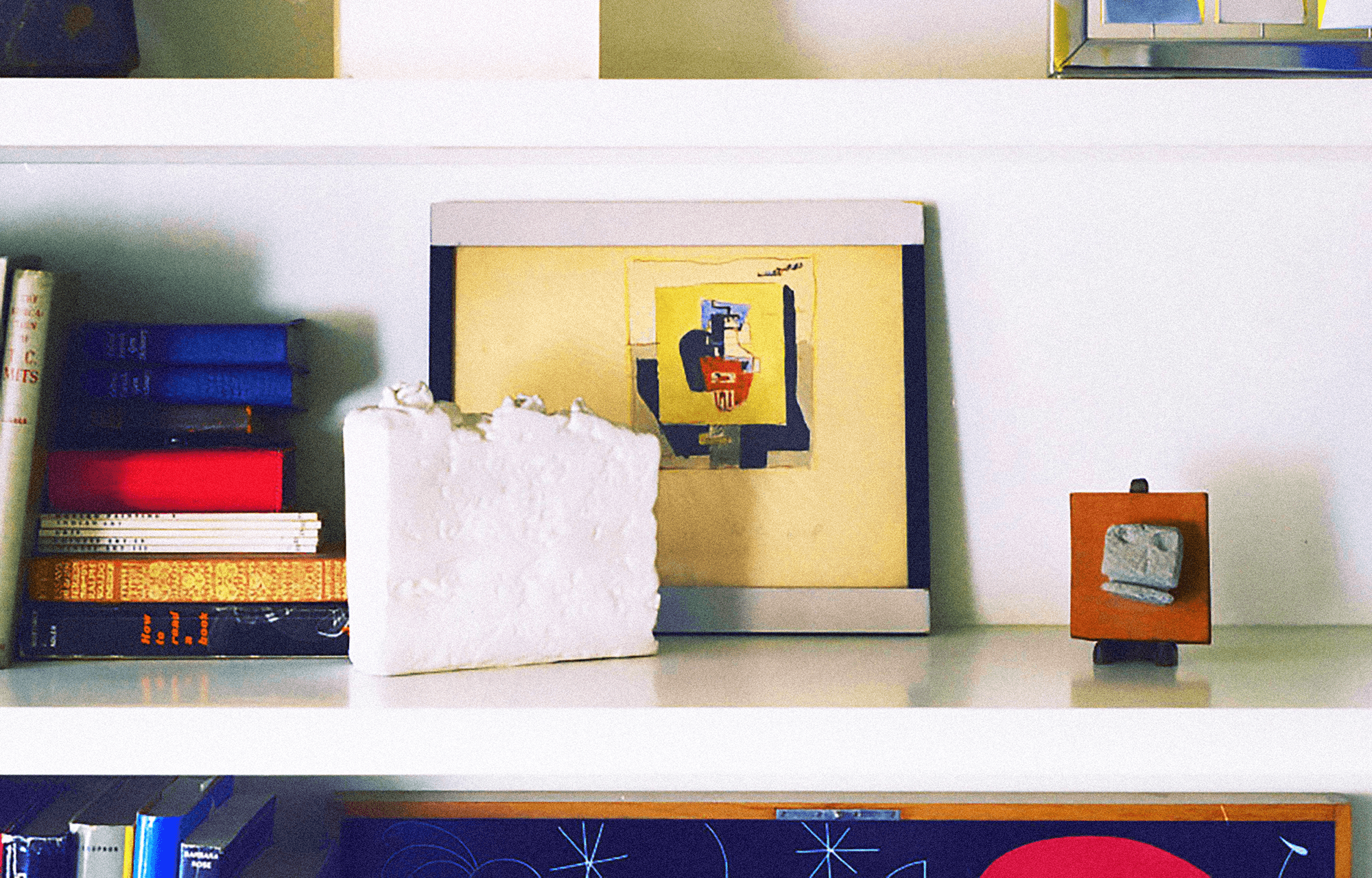

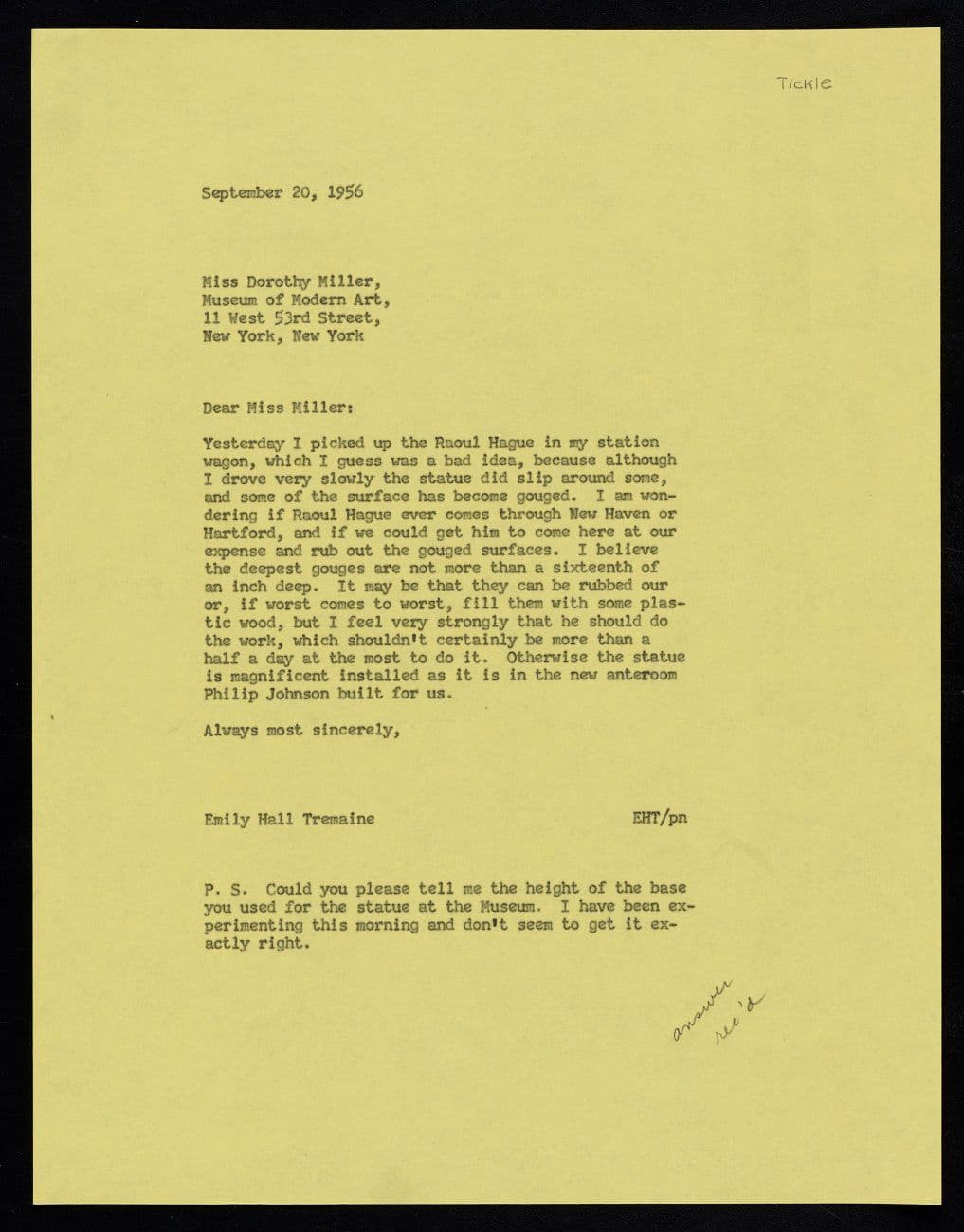

The renovated barn was spacious enough to house large works. One of the first to be placed there was Raoul Hague’s Swamp Pepperwood. Born in Istanbul, Hague had turned to wood in the late 1940s creating sensuous forms, in this case a torso, taking advantage of the natural grain. By the fireplace stood Hilary Heron’s Girl with Pigtails carved from oak. There was also Neil Jenney’s painting Husband and Wife, which led to frequent discussion among the visiting Tremaine grandchildren as to what the argument portrayed in the painting was all about.

Swamp Pepperwood, Raoul Hague, in foreground. Girl with Pigtails, Hilary Heron, by fireplace. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Because of its fragility, Oldenburg gave the Tremaines some jars of paint and a small brush for touch-ups.

Heron was an Irish sculptor who sometimes imbued her work with an ancient Celtic quality as can be seen in the cross-hatched pigtails. Four and a half feet tall, Girl with Pigtails was small enough to be moved around; occasionally it was placed near the door as if she were looking out. Claes Oldenburg’s Street Head I hung from the barn’s high ceiling like a giant wasp’s nest. Made of papier-mâché, Street Head wouldn’t have lasted a minute outside. Because of its fragility, Oldenburg gave the Tremaines some jars of paint and a small brush for touch-ups.

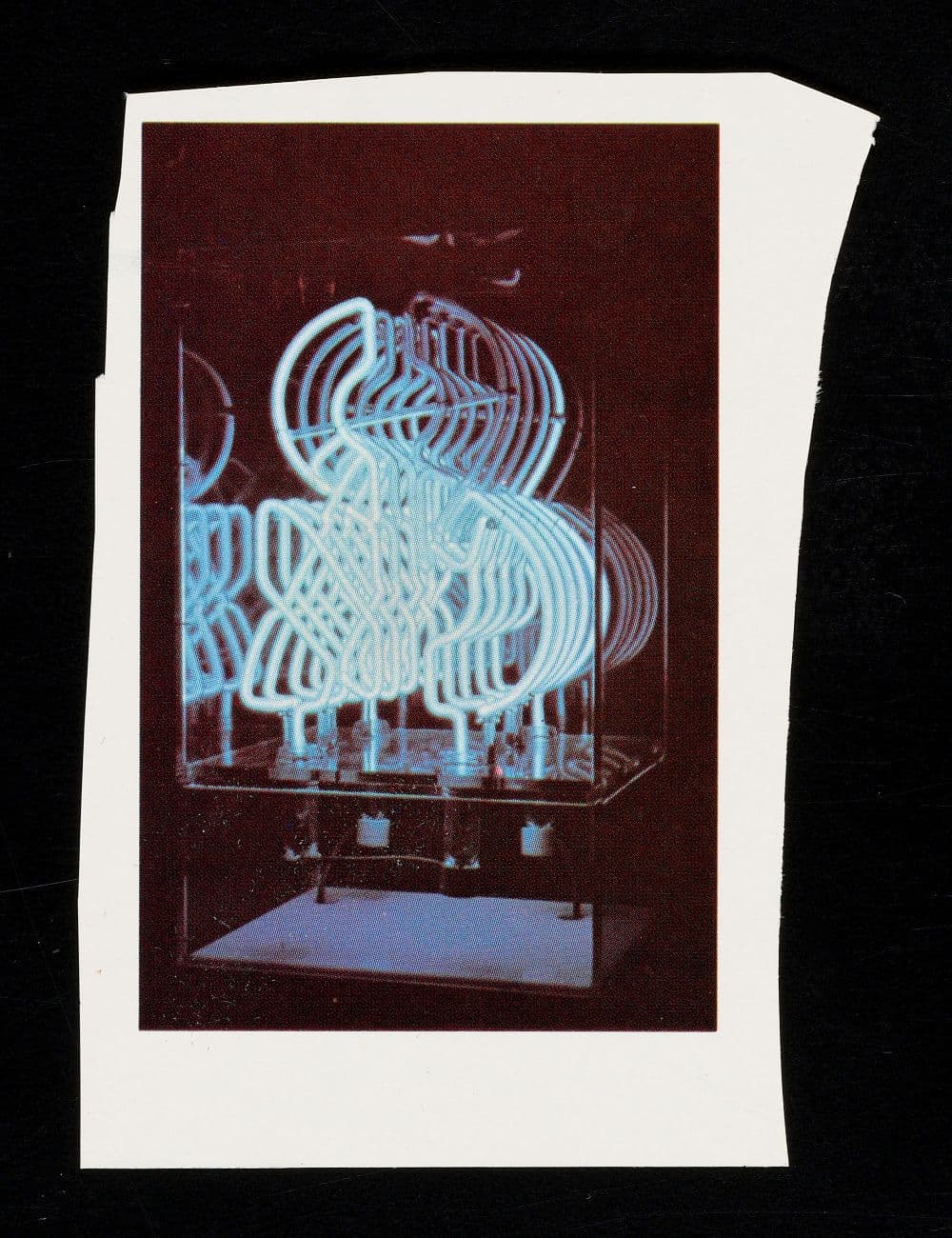

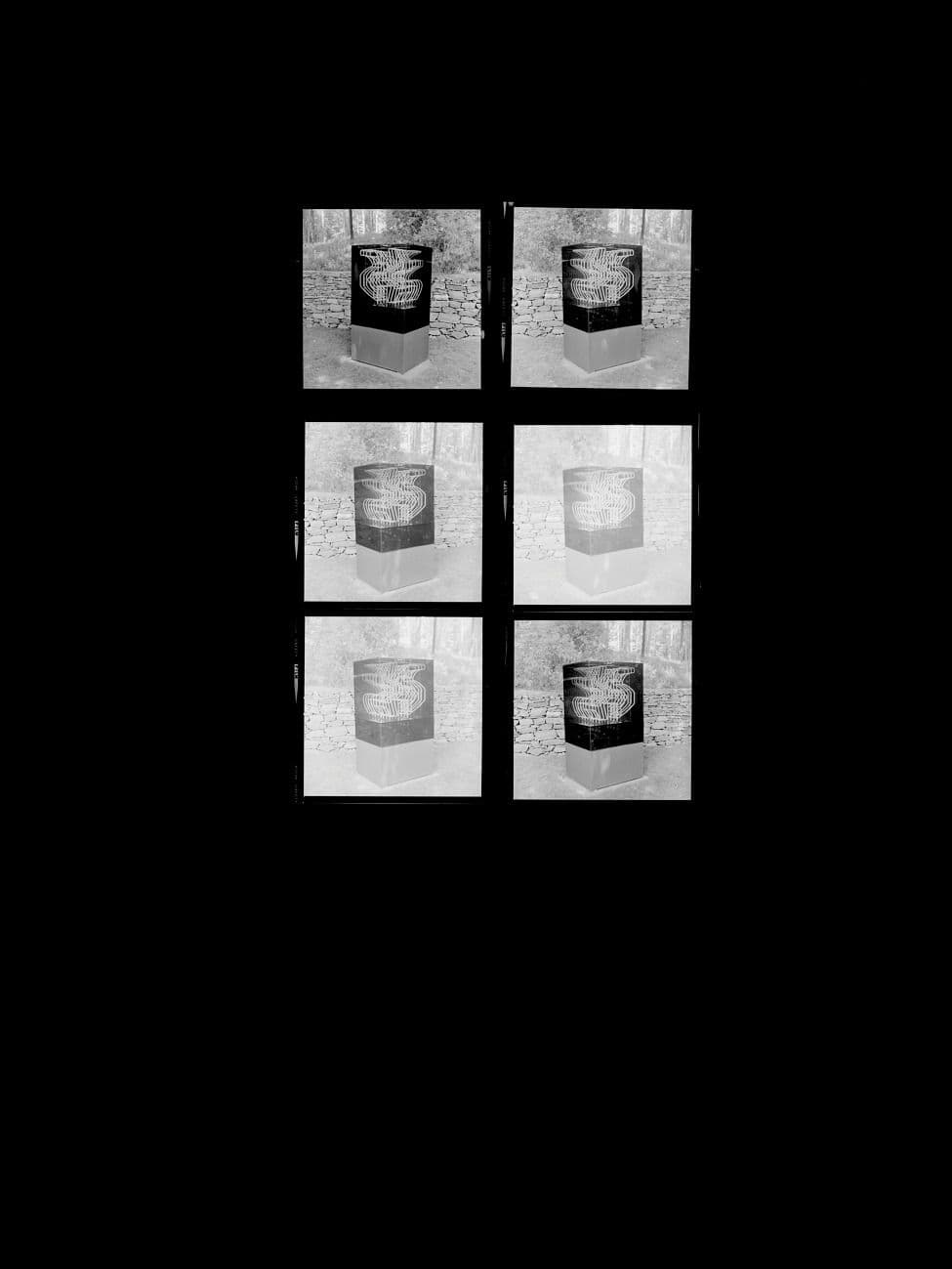

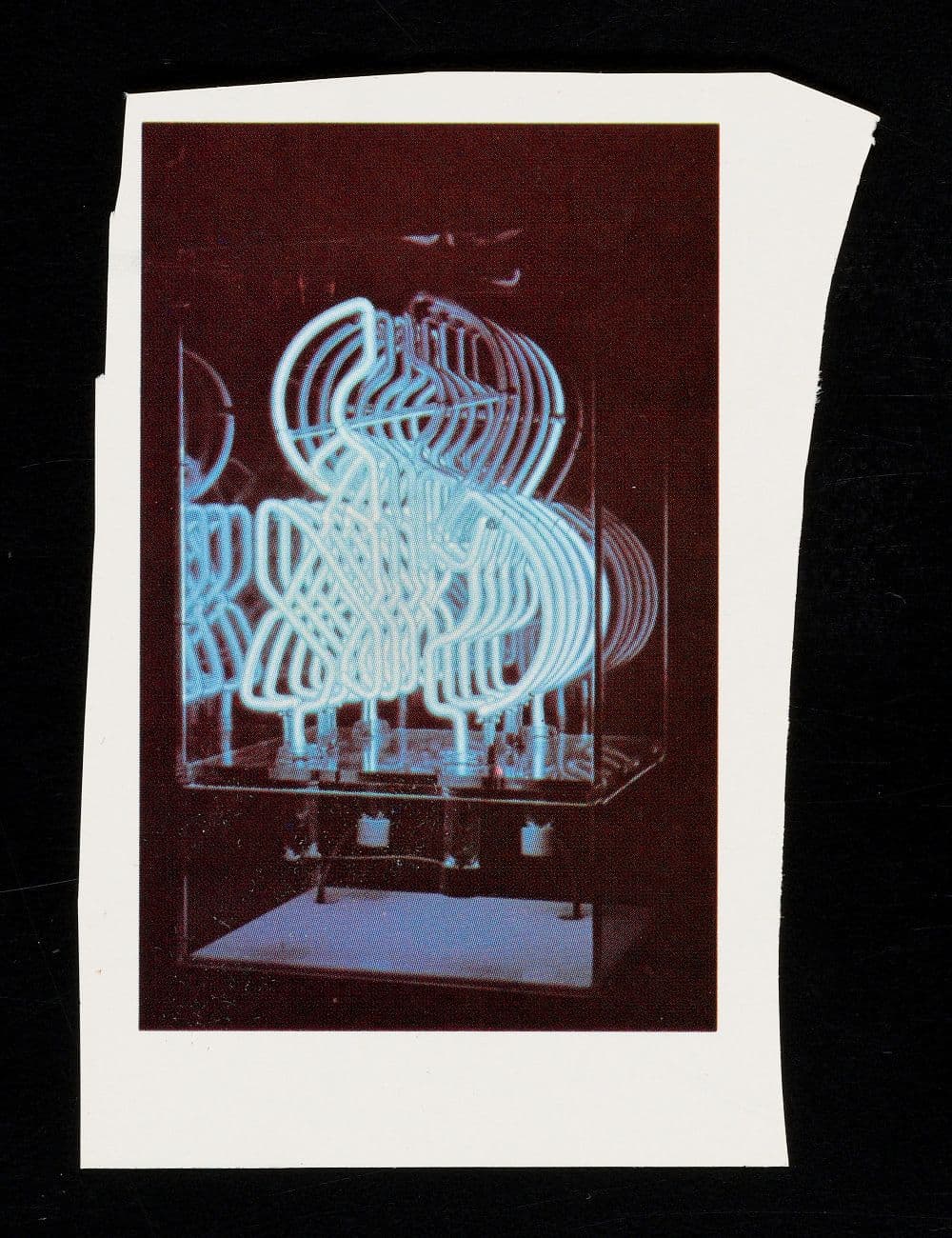

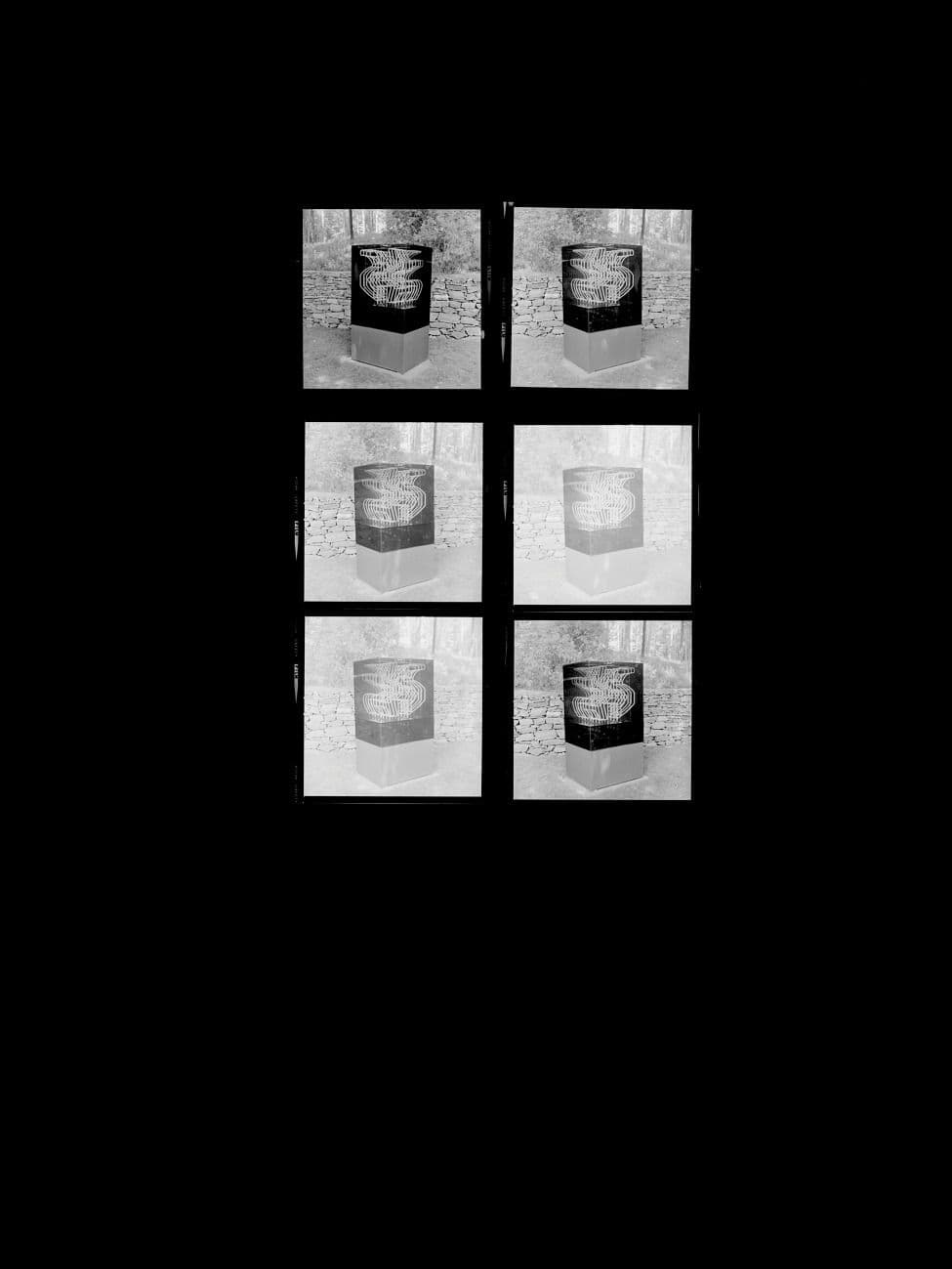

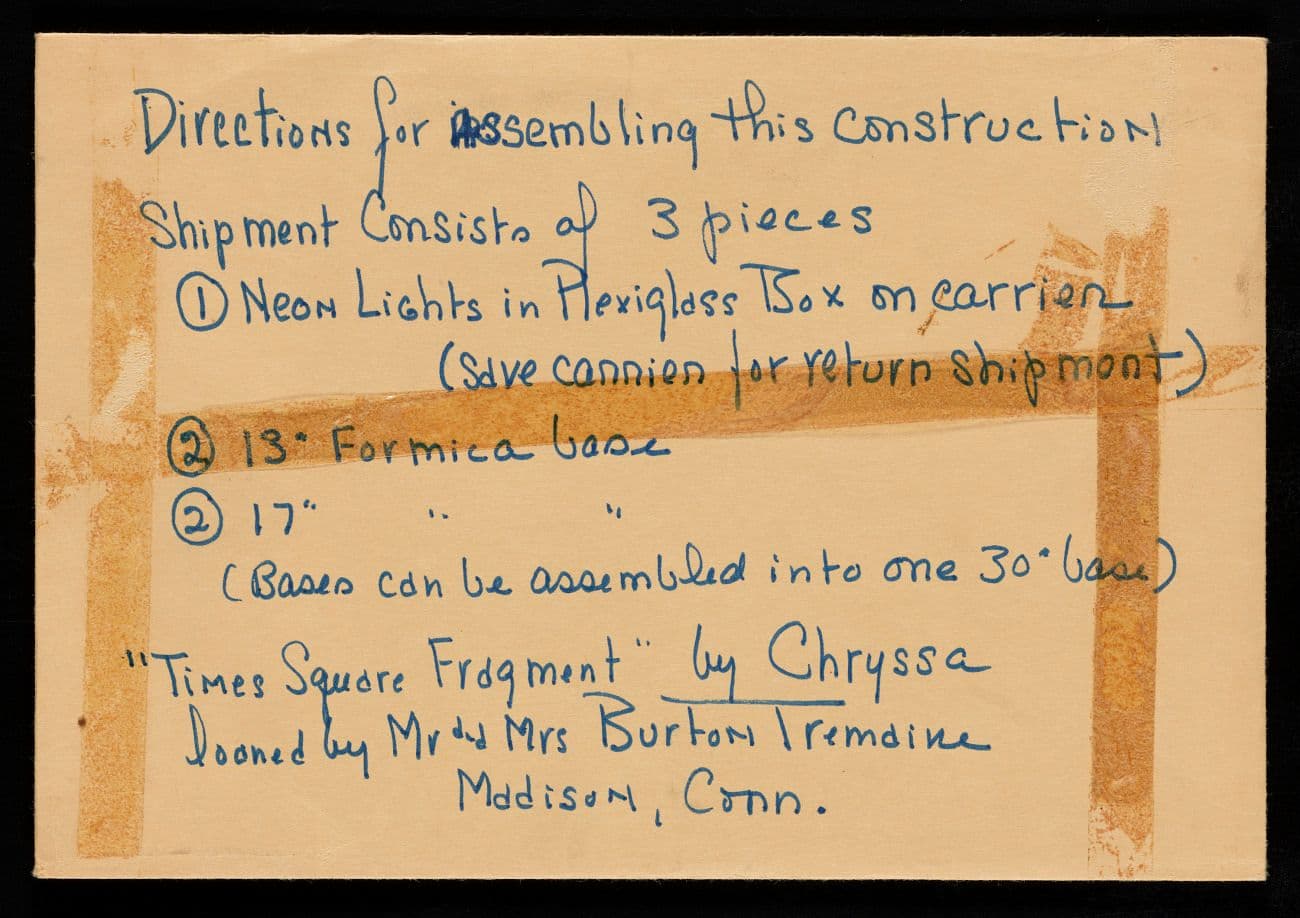

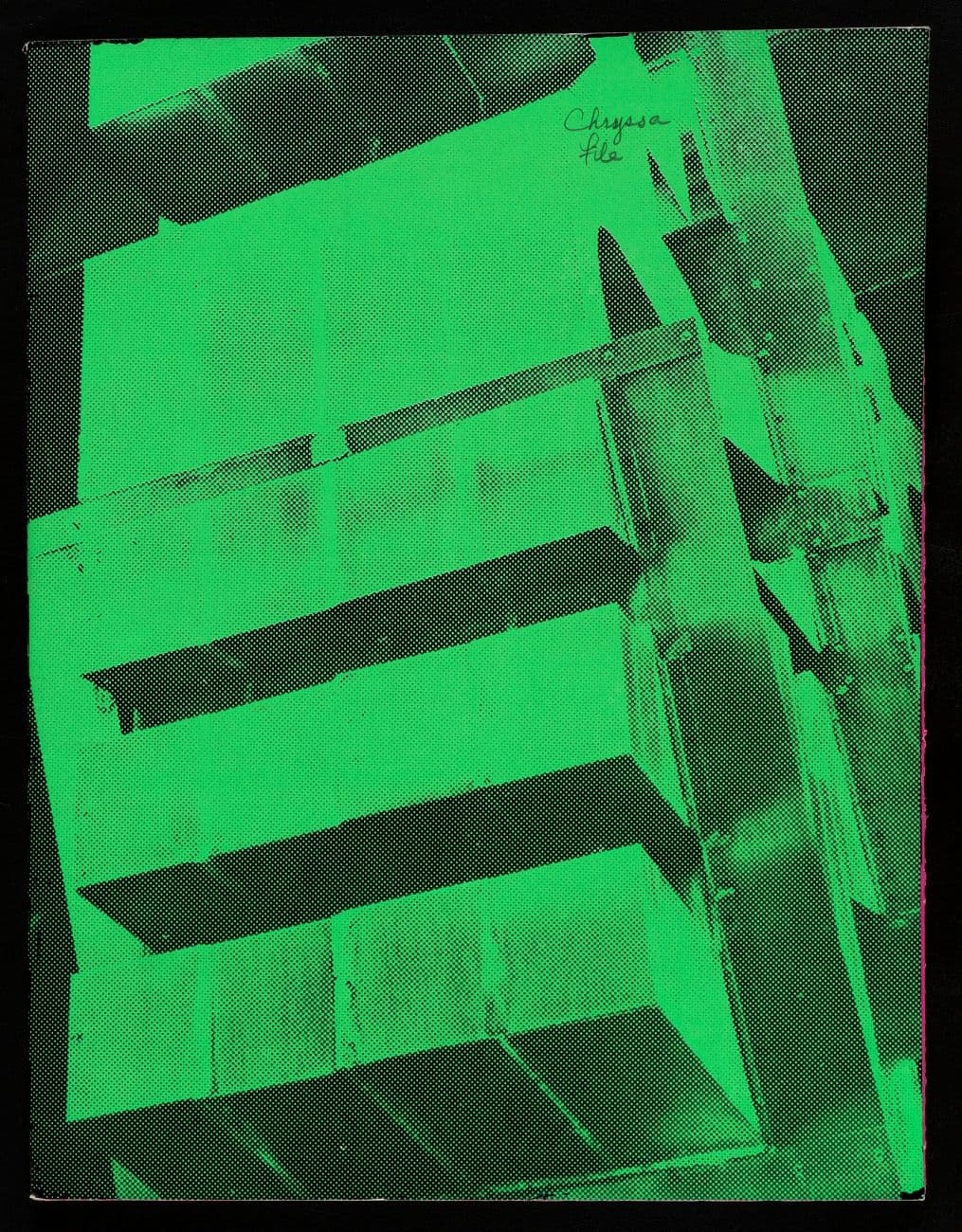

Fragment for the Gates to Times Square by Chryssa at the Tremaines’ property in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

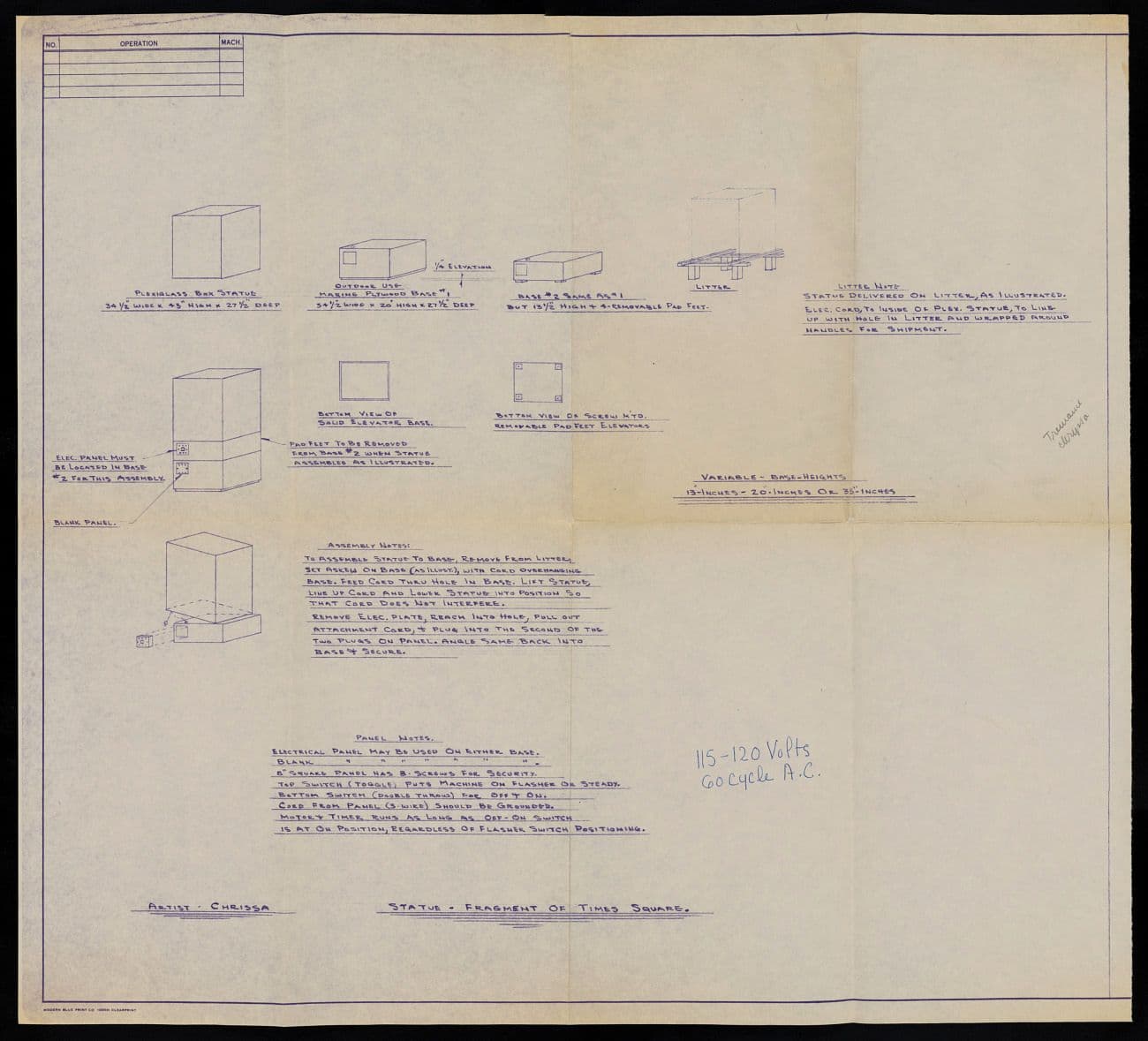

This brings up the issue of durability. Outdoor sculpture must be able to withstand the elements, which is why stone and metal are favored. Chryssa’s Fragment for the Gates to Times Square required electricity to power the flickering neon lights encased in a smoky Plexiglas box that could break. Eventually, it was placed by the stone wall near an electrical outlet but not before the Tremaines queried the art dealer about whether it was impervious to the weather. Not so imperious was Riot Glass by Guy Dill. An actual storefront window that had been hit by a projectile or a bullet but had not broken apart, Riot Glass stood in the garden for two years until a hurricane reduced it to shards.

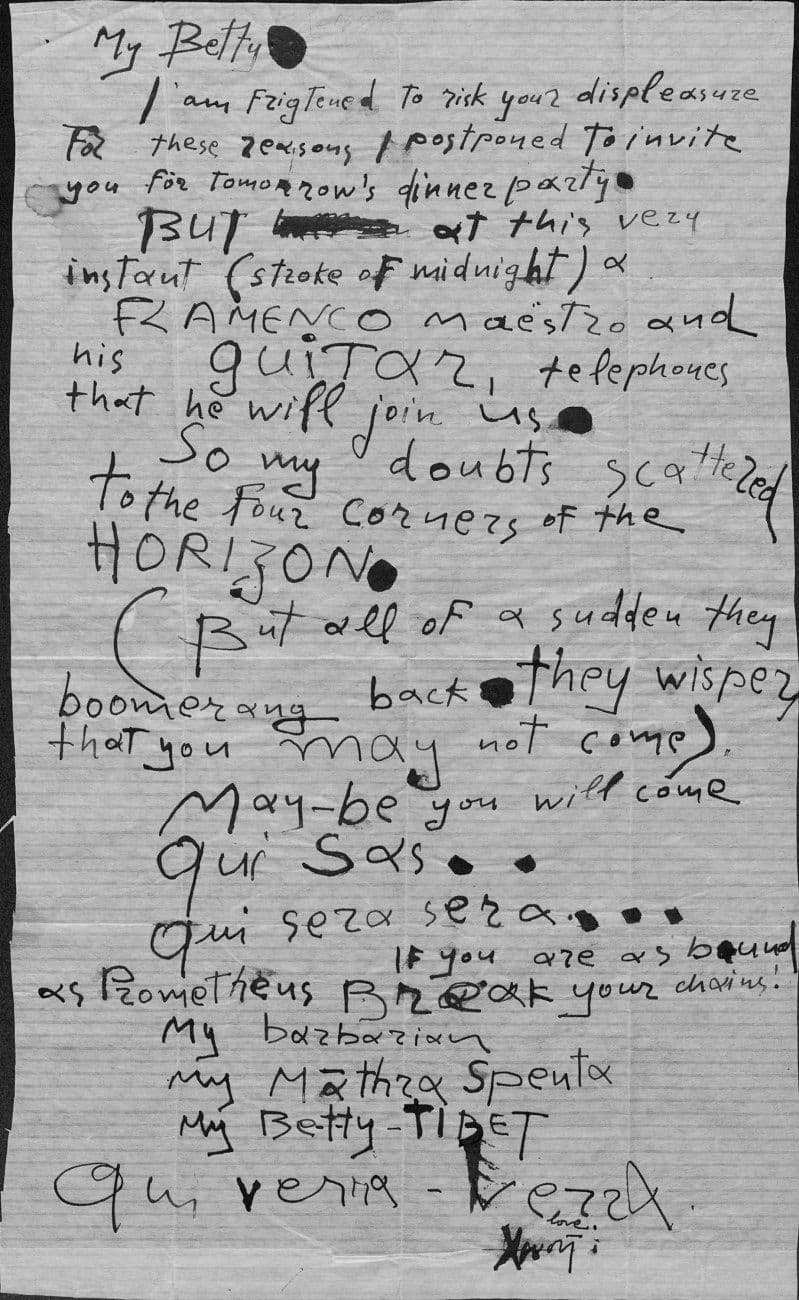

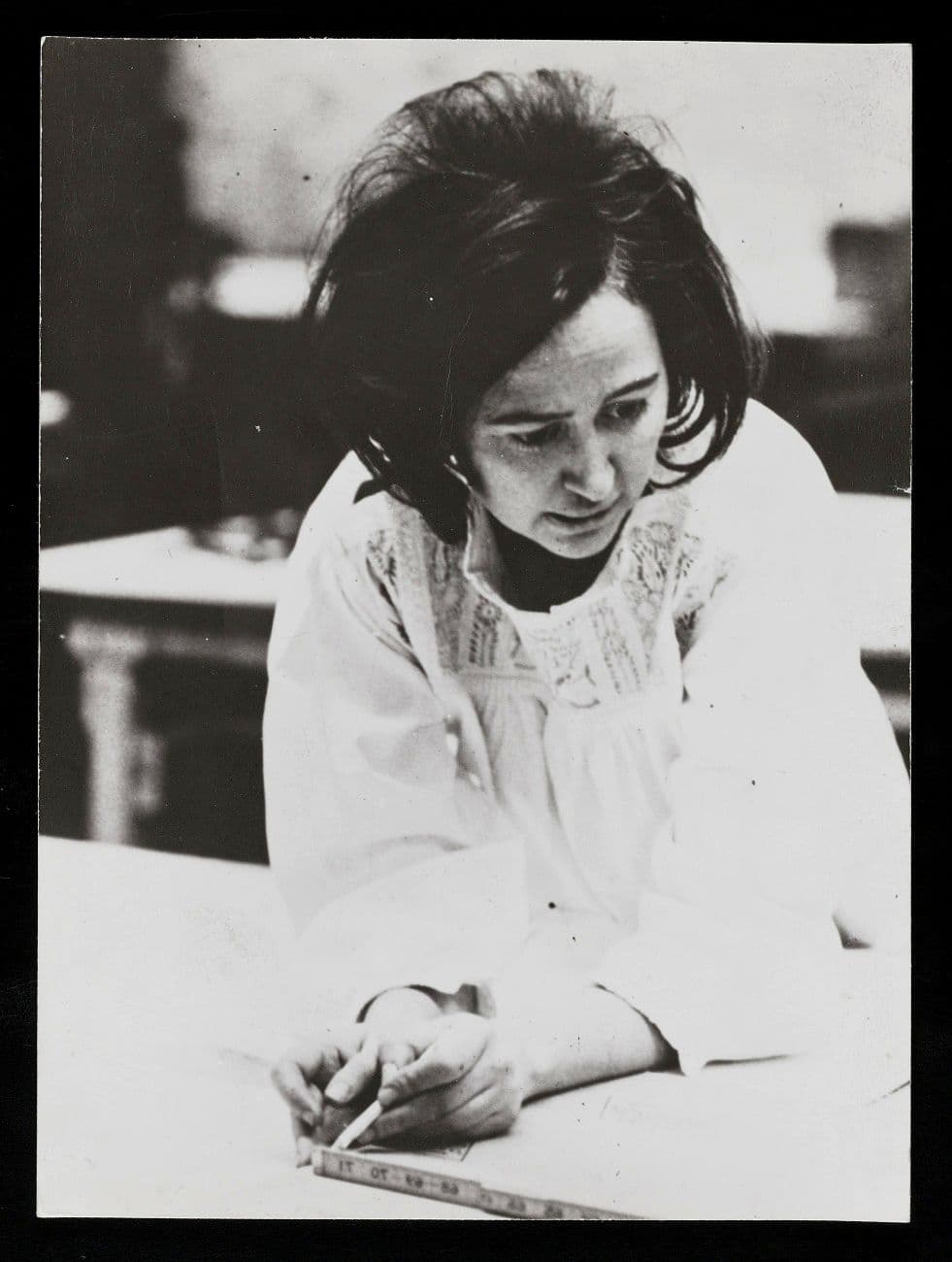

From the Archives

From the Archives

Size was also a problem. It was prohibitively expensive to set a massive piece in place. Furthermore, a sculpture in the country was very different from one in the city. This can be seen with Gyre that was placed for a while in Penn Center before the Tremaines purchased it. Not only was the space different but so too was the energy. Surrounded by skyscrapers, it seemed to droop, whereas in Madison it seemed to bloom. In a speech in 1964, Tremaine told the audience that she had wanted to include a large sculpture for their consideration. “But to bring it would present as difficult a problem as Mark di Suvero did last week when he wanted us to install a new piece of his work that includes a 24-foot beam.”

Alexander Liberman, Gyre, 1966, in Penn Center. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

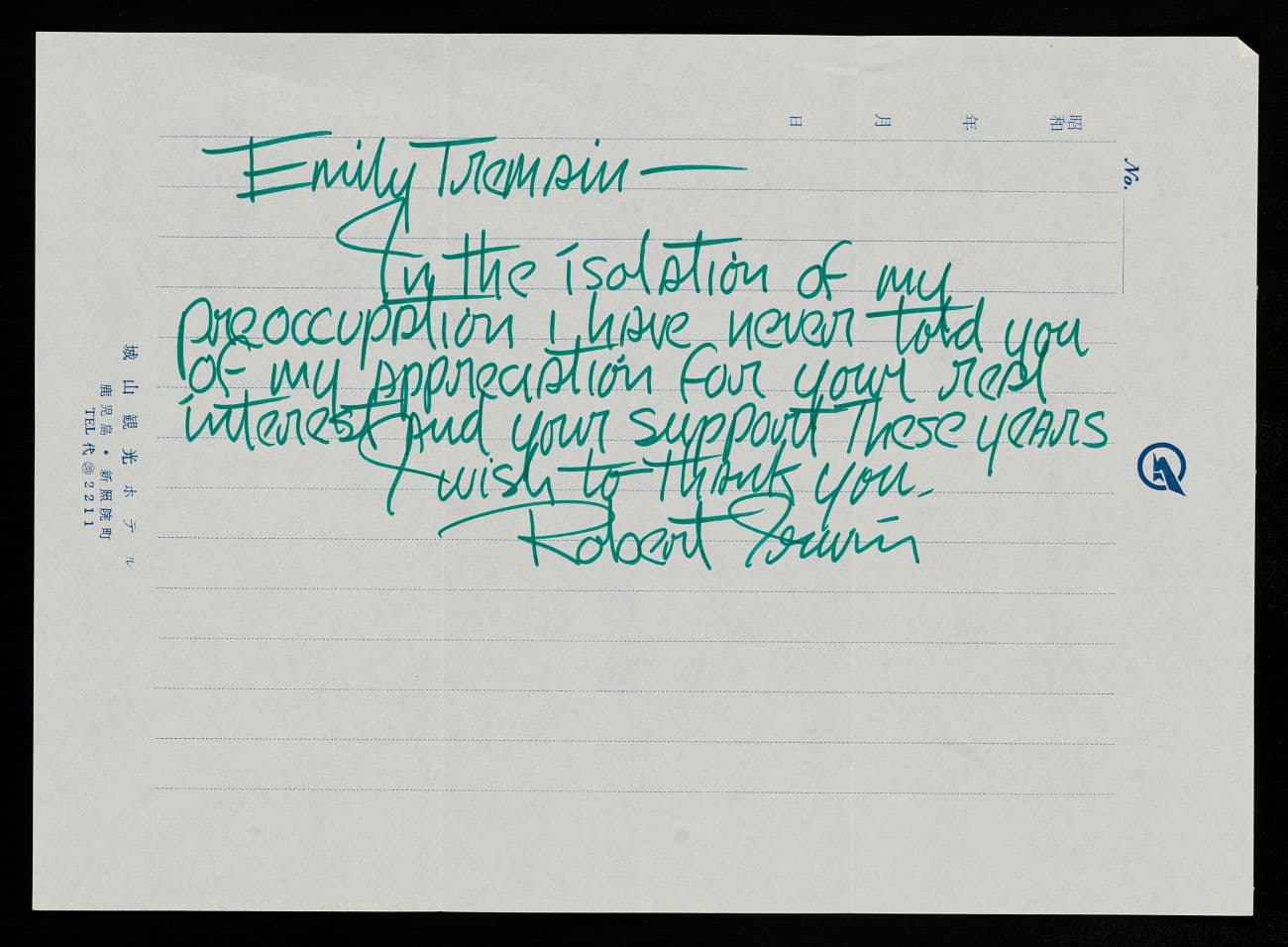

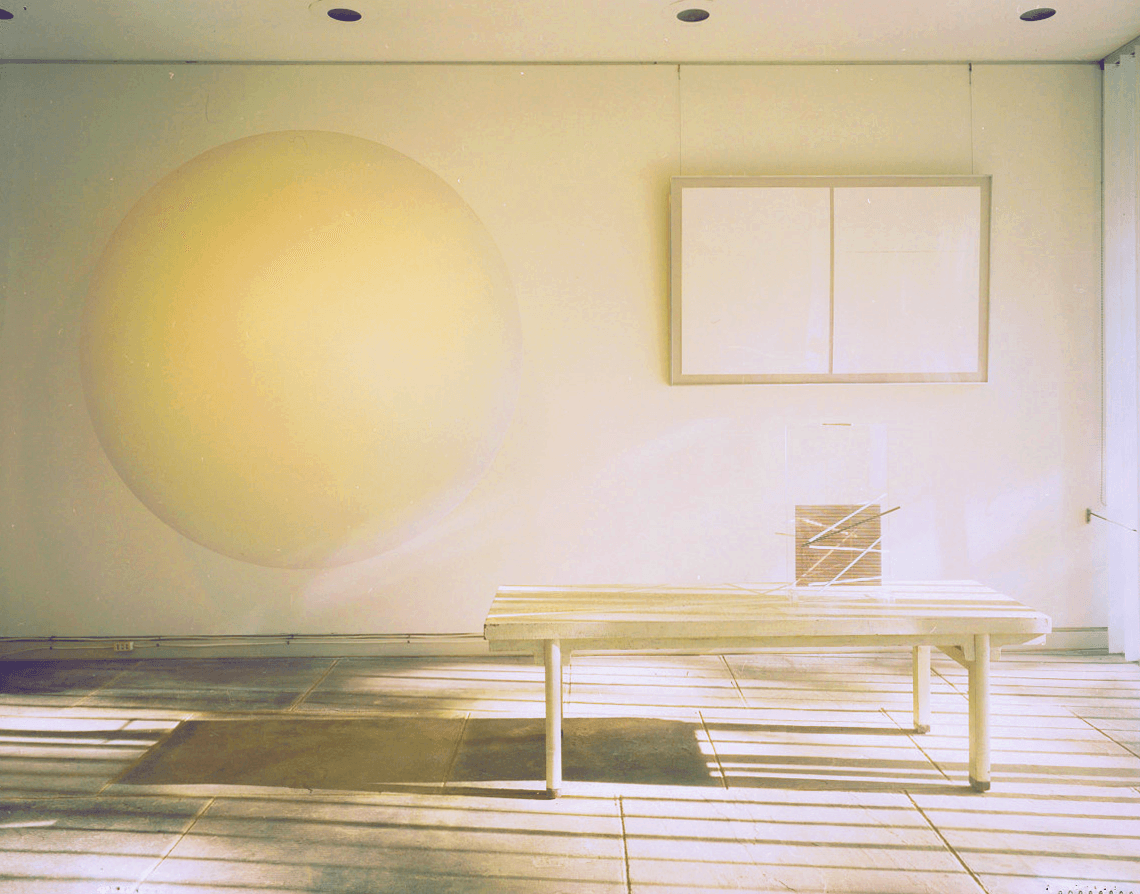

Yet the Tremaines were willing to put up with the difficulty when a work was worth it. Such was the case for Robert Irwin’s glowing disk Untitled made of plastic on cast acrylic with electric lights, for which the Tremaines rebuilt their foyer. Of their efforts, Gene Baro, an art journalist, wrote in Vogue Magazine in February 15, 1969, “A secret of this success is that the Tremaines have in general a taste for works that create environment. But they are also alert to the art that requires special handling in order to come into its own. They are restructuring a room in their Connecticut house to accommodate the peculiar demands for lighting and space of a Robert Irwin painting they have recently acquired. Few collectors would be willing to go to this proper trouble.”

The Tremaines’ Madison home with Untitled by Robert Irwin, a drawing by Walter De Maria, and a sculpture by Jesus Rafael Soto, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The only other art in the foyer was a sculpture by Jesus Rafael Soto and a drawing by Walter de Maria that he had given to the Tremaines in thanks for permitting him to use their Arizona ranch, the Bar T Bar, for the prototype of his Lightning Field (now owned by the Dia Arts Foundation). In an interview for Archives of American Art, the art dealer Leo Castelli observed that for certain artists, “nothing but the mountain or desert is big enough to place some work of theirs into.” Not put off by the demand for vast space, the Tremaines revamped the idea of what a sculpture garden was supposed to look like and provided a desert waiting for a thunderstorm.

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: The Tremaines' home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. From Alexandra Tremaine. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.