Story

Big Impact, Small Paintings:

The Tremaine Miniature Collection

When the art critic Susan Tallman visited the twin exhibitions Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2021, she was rhapsodic about a very small painting, Gray Numbers. “It is possible to look at the wallet-sized Gray Numbers for a long time and feel it change in your mind,” she wrote in The New York Review of Books.

What Tallman did not know was that Jasper Johns had painted Gray Numbers specifically for Emily Hall Tremaine. “I was in South Carolina when I did Gray Numbers for Emily’s miniature collection as a gift,” Johns recalled. By then the Tremaines had already acquired White Flag, Three Flags, Tango and Device Circle, and had come to know Johns personally helping to build his reputation among collectors and museums.1

1—Interview with Jasper Johns by author, 1998.

Photo of Jasper Johns, Grey Numbers, 1961. Encaustic on canvas, 5 ¾" × 4 ¼", 1961. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In the early 1960s when he painted Gray Numbers in his studio on Edisto Island in South Carolina, Johns was struggling to find a way forward. “I had the sense of arriving at a point where there was no place to stand,” he said. The use of gray was one of the ways he sought to regain his balance. In the painting, some of the numbers loom out as if through a dense fog while others recede. Tremaine wrote, “When I look at Jasper’s number and letter paintings, I think of a critique I once read on Sarah Bernhardt. It said she could recite the alphabet and bring tears to your eyes.”

A private person, Tremaine appreciated the intimacy—the one-viewer-at-a-time perspective—of a miniature.

Too often the word miniature implies something not just reduced in size but diminished in impact, turning it into a kind of curiosity. Not so Tremaine’s small-frame works. All were capable of holding their own. A private person, Tremaine appreciated the intimacy—the one-viewer-at-a-time perspective—of a miniature. She grouped some of them together on a wall in a hallway, which encouraged close-up viewing as well as comparisons, such as how Pablo Picasso influenced Willem de Kooning—their paintings separated by only a few inches.

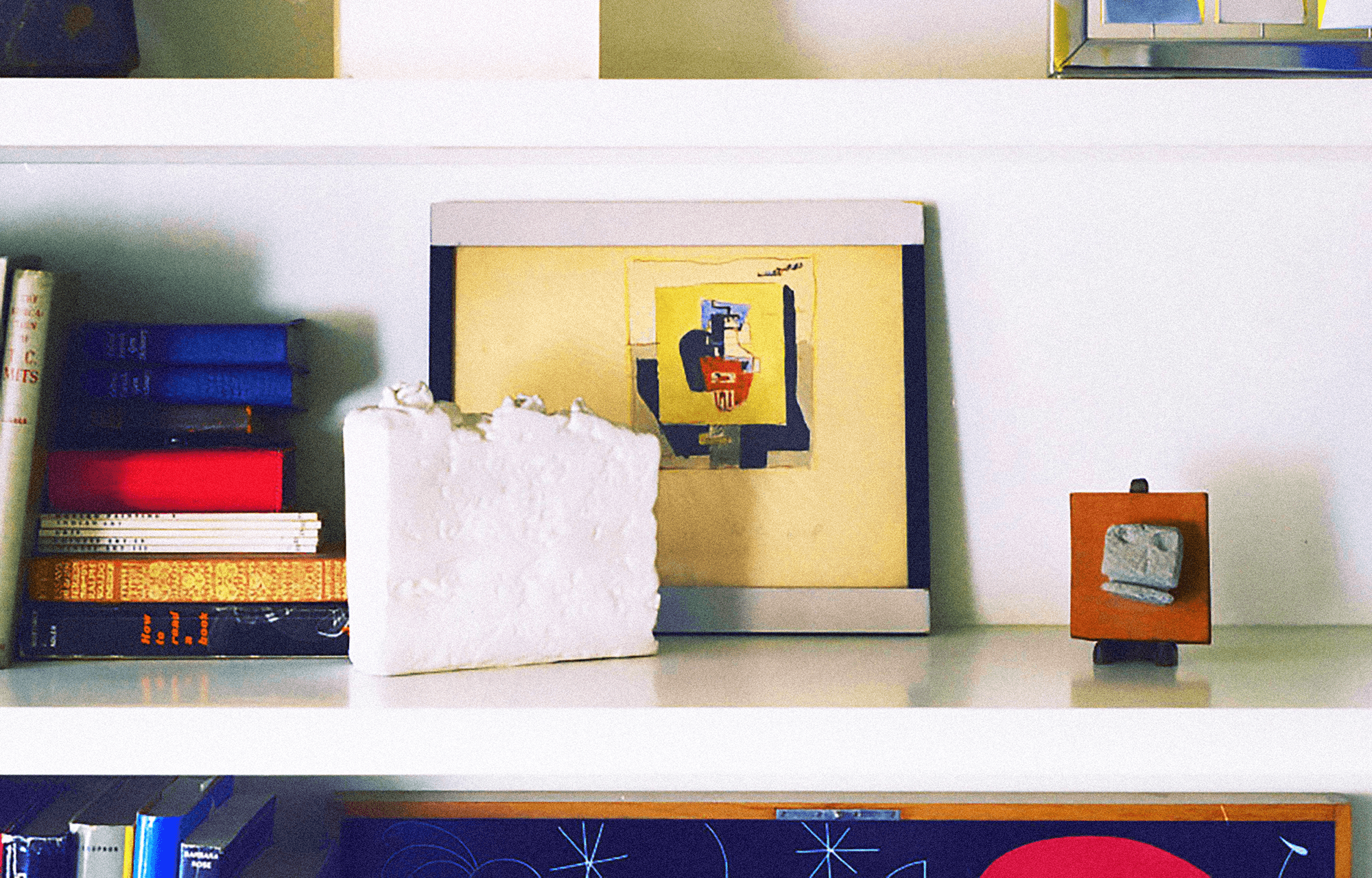

Part of the Tremaines collections of miniatures on display in their New York City apartment, circa 1984. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The miniatures in the hallway were: (top row, l. to r.) Pablo Picasso’s New Hebrides Mask, Ad Reinhardt’s Blue Composition; (middle)Jean-Paul Riopelle’s Printemps, Willem de Kooning’s Yellow Woman, Robert Motherwell’s Spanish Elegy, Jackson Pollock’s Silver and Black, Louise Nevelson’s Moon Garden Series; (bottom) Marcel Duchamp’s Self-Portrait in Profile, and a work by Man Ray.

There were also small sculptures displayed on mantels and shelves, including a plaster face and a stone mounted on wood. The Tremaines liked to challenge visitors to guess who had made them, finally revealing that their grandsons, Burton (Tony) and John, were the sculptors. Conversely, they challenged all their grandchildren to search the collection for newly acquired works, encouraging discussion.

Tom Wesselmann, Great American Nude, in the Tremaines' Madison, CT bedroom with miniatures by door. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

There were even some tiny pop paintings. The Tremaines owned several of Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude series, the largest being 47 ½ inches in diameter and the smallest, No. 8, being only a mere five inches in diameter. They owned Roy Lichtenstein’s aptly named Small Landscape at only 4 ½ x 4 ⅜ in. Tremaine remarked that Lichtenstein was one of the few artists who had the “slyness” to present the “banal” so that people would take a look.

Warhol was so grateful to Tremaine for acquiring his art and helping to build his reputation that one Christmas morning he left the silkscreen leaning at her apartment door as a gift.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, 1962. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

There were also Andy Warhol’s Red Airmail Stamp and Small Blue Flowers. And while it wasn’t exactly a miniature, his small gold Marilyn Monroe is worthy of mention. Warhol was so grateful to Tremaine for acquiring his art and helping to build his reputation that one Christmas morning he left the silkscreen leaning at her apartment door as a gift.

From the Archives

From the Archives

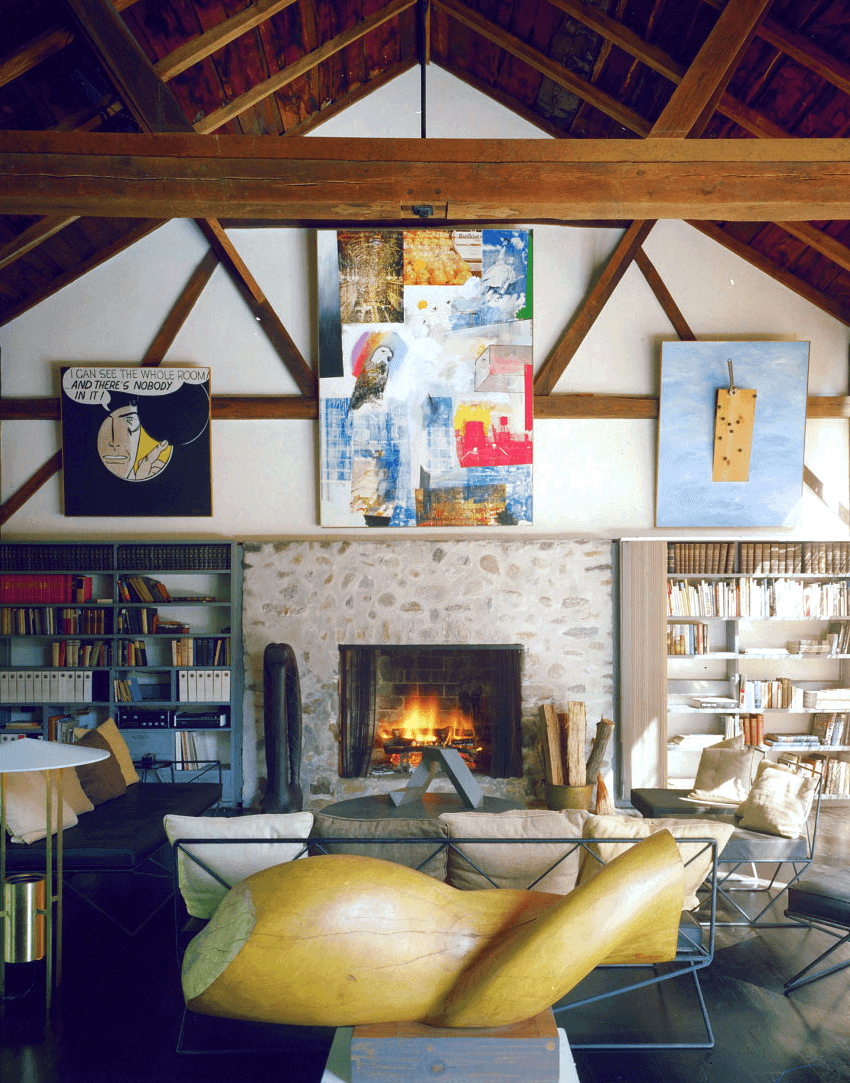

During the 1950s paintings became larger creating major headaches for collectors. Museums could cope with the size easier than private collectors who had limited wall space. For the Tremaines, their remodeled barn in Connecticut helped to alleviate the problem but not completely. Robert Rauschenberg’s Windward was a gigantic eight feet tall and almost six feet wide. Because of their scale, these works tended to hog attention. That meant the placement of small paintings had to be handled with care so they weren’t overwhelmed.

Small-format paintings have something unique to offer—they can shift the nature of perception. For example, color can create a different visual response when an entire canvas is taken in at a single glance and all its components are processed at once. This is markedly different from the eye movement required to move around a large canvas.

Robert Rauschenberg's Windward (center), Raoul Hague's Swamp Pepperwood in foreground, and Hilary Heron's Girl with Pigtails by fireplace. in Tremaine barn at the Madison house, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Small-frame paintings face a totally different set of issues when they are printed in a book or appear on a computer screen, which is the way most people view them. Scale is out of whack—big paintings appear small and small paintings appear big. An egregious example from the Tremaine exhibition catalog 20th Century Masters: The Spirit of Modernism involves the work of Willem de Kooning. On the left page is Yellow Woman, demanding attention by means of contorted lines and harsh colors. On the right is Villa Borghese appearing to be smaller and tamer. But Yellow Woman is a mere 8 ½ x 5 ½ inches while Villa Borghese is a whopping 80 x 70 inches.

Willem de Kooning's Villa Borghese, 1960 (right of fireplace) in the Tremaine’s living room. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While several of de Kooning’s women paintings were far larger, none was more visually assertive than Yellow Woman. “It’s really absurd to make an image, like a human image, out of paint today, when you think about it,” de Kooning said.“But then all of a sudden it was even more absurd not to do it.” It is likely that working in a small format allowed de Kooning to solve issues of composition, line and color.

Harry Bowden. Willem de Kooning, 1946 Apr. Harry Bowden papers, 1922-1972. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Small was also a way to experiment before moving to a large format. For some artists, the compelling reason to paint small was to see if they could get the same impact as big. The prolific Canadian artist Jean-Paul Riopelle’s visceral Printemps is a case in point. He was fascinated with the actual feel of a painting, often referring to his art as “sculptures in oil.” Indeed Printemps is visceral, even gnarly. Placed against one of his large paintings it conveys the same power.

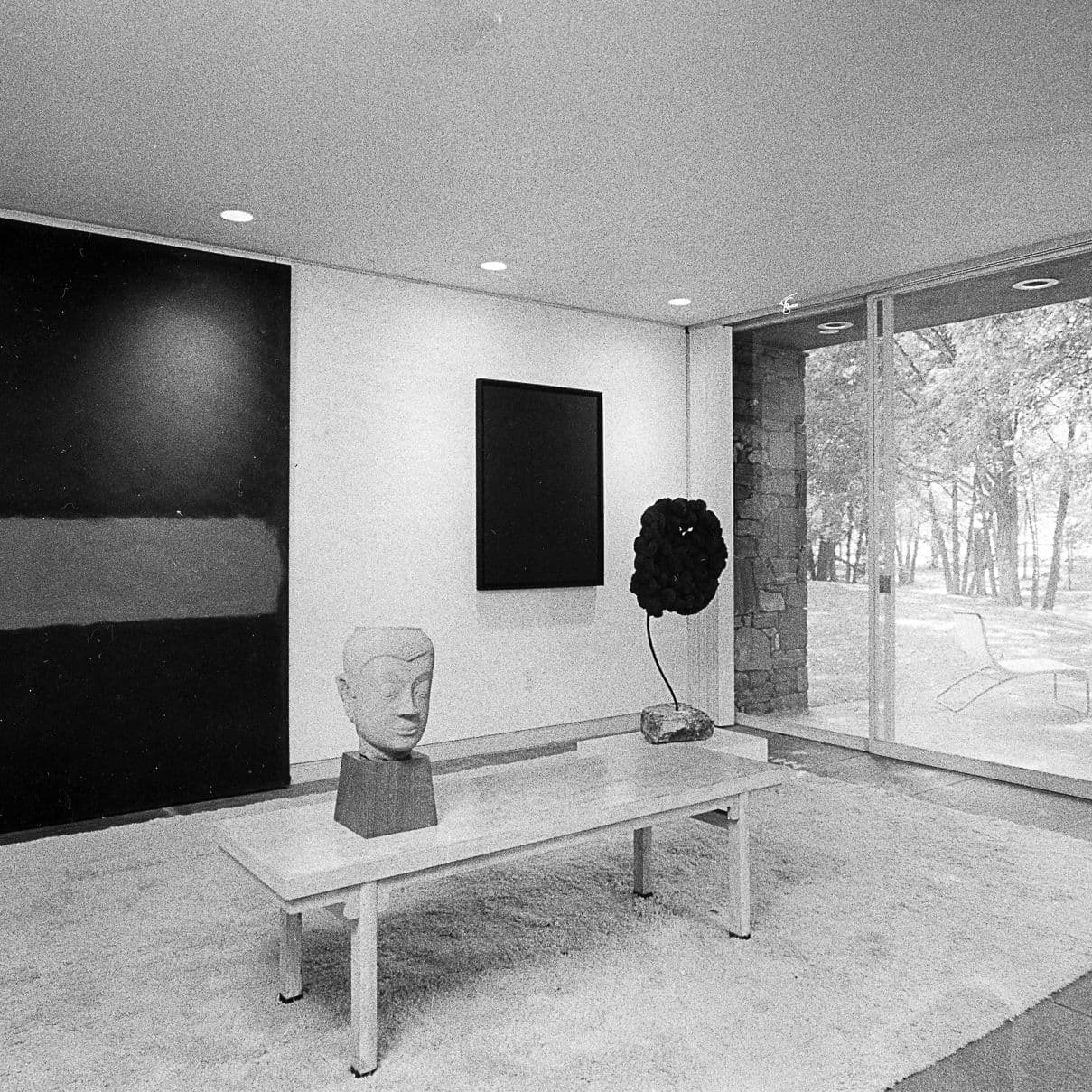

The same principles hold for sculpture. As the artist and teacher Hans Hofmann liked to tell his students,“It isn’t necessary to make things large to make them monumental; a head by Giacometti one inch high would be able to vitalize this whole space.” Tremaine’s placement of Man Walking Quickly Under the Rain beautifully proves his point.

Giacometti, Man Walking Quickly Under the Rain. Joan Miró, Le Chat Blanc on the wall of the Tremaines' home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Alberto Giacometti Estate / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s watercolor No. 10 was one of the smallest paintings (6 ¼ x 3 in.) in Tremaine’s collection. Taeuber-Arp was a Swiss artist with very broad talents encompassing textiles, painting, sculpture, dance and what would now be called performance art but which at the time was a component of dada. An intentionally chaotic and creative reaction to the terrifying irrationality of World War I, dada was where Taeuber-Arp’s career began, but her interests went far beyond it. No. 10 was an early work (1916-19) in geometric abstraction in subdued red, black, ochre, blue, and white.

Jean Arp, Human Lunar Spectral, 1958. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The Tremaines purchased No. 10 in 1957 from Taeuber-Arp’s husband, Jean Arp, at the time they commissioned him to cast in bronze his sculpture Human Lunar Spectral. Among art couples, Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp were a rarity because they were totally supportive of each other. When Taeuber-Arp died in 1943 from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a faulty heater, Arp was devastated. It is impossible to view Human Lunar Spectral without feeling his grief. So also Tremaine had lost her first husband under tragic circumstances. She cited the sculpture in the garden of their Connecticut home and hung No. 10 in the bedroom of the New York apartment.

As for Gray Numbers, it was also in some ways a work of grief. Johns went on to paint many larger works in which gray predominated. The poet and art critic John Ashbery once wrote that when it came to gray Johns longed to explore “what it is, where it comes from, how it both begins and ends in light.” So also, small paintings can have about them an allure that comes from their pulling the viewer in close. Their beginning and ending is a kind of epiphany—providing an “aha” moment of the smallest kind.

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: The Tremaines’ Madison home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.