Story

The Light and Dark City

in the Tremaine Collection

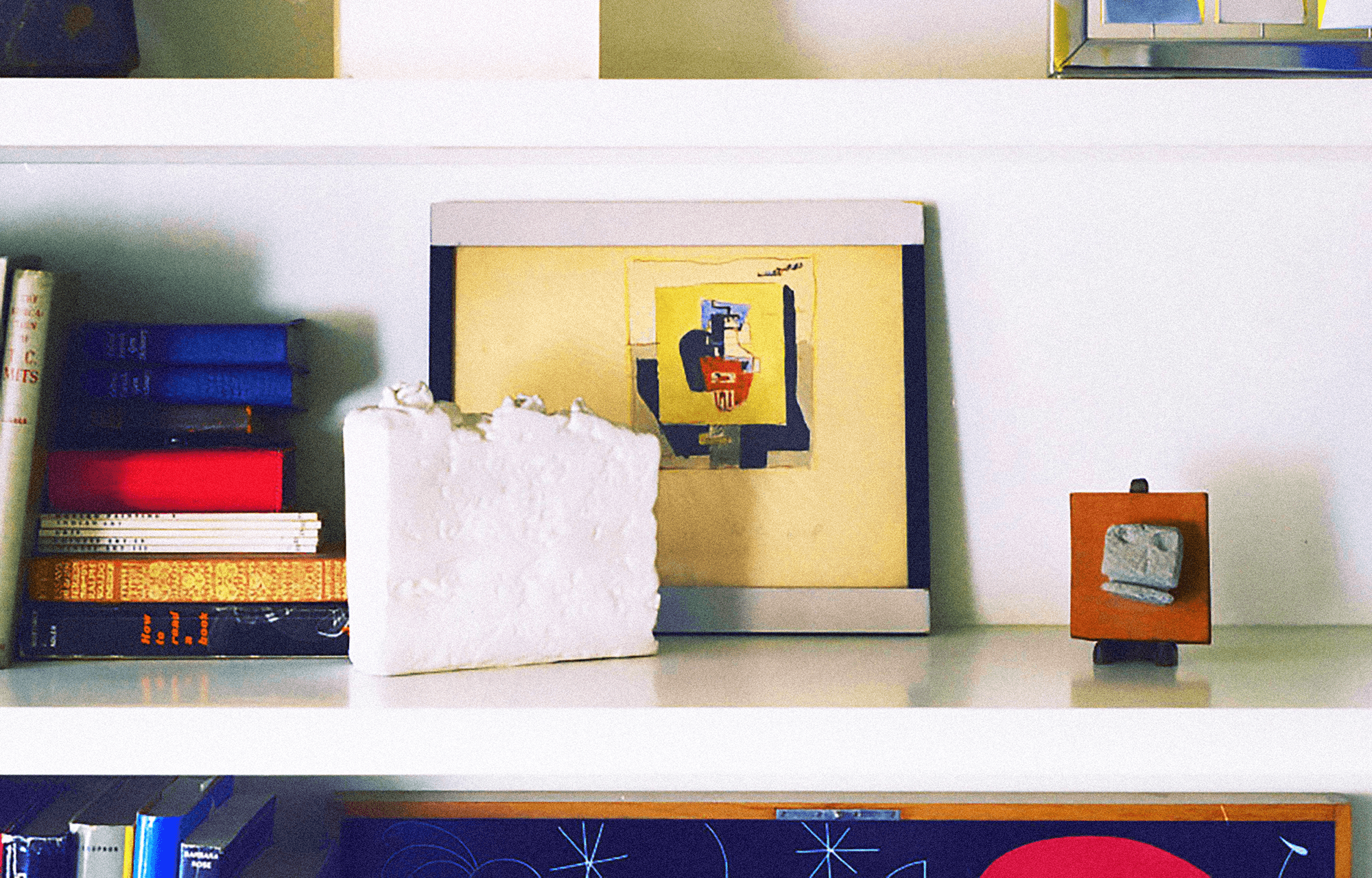

An unusual aspect of the Tremaine collection of modern art was that it had a recurring motif of the city. It was not as if Emily Hall Tremaine covered her walls with urban landscapes in the same way a collector of seascapes covered her walls with ships. The city motif was subtle, in alignment with Tremaine’s interest in the architectonic and her regard for the real city of crowded streets, neon signs, and shoeshine stands. Windward by Robert Rauschenberg is an example with its dynamic imagery of factories, skyscrapers, even an eagle.

The city motif was subtle, in alignment with Tremaine’s interest in the architectonic and her regard for the real city of crowded streets, neon signs, and shoeshine stands.

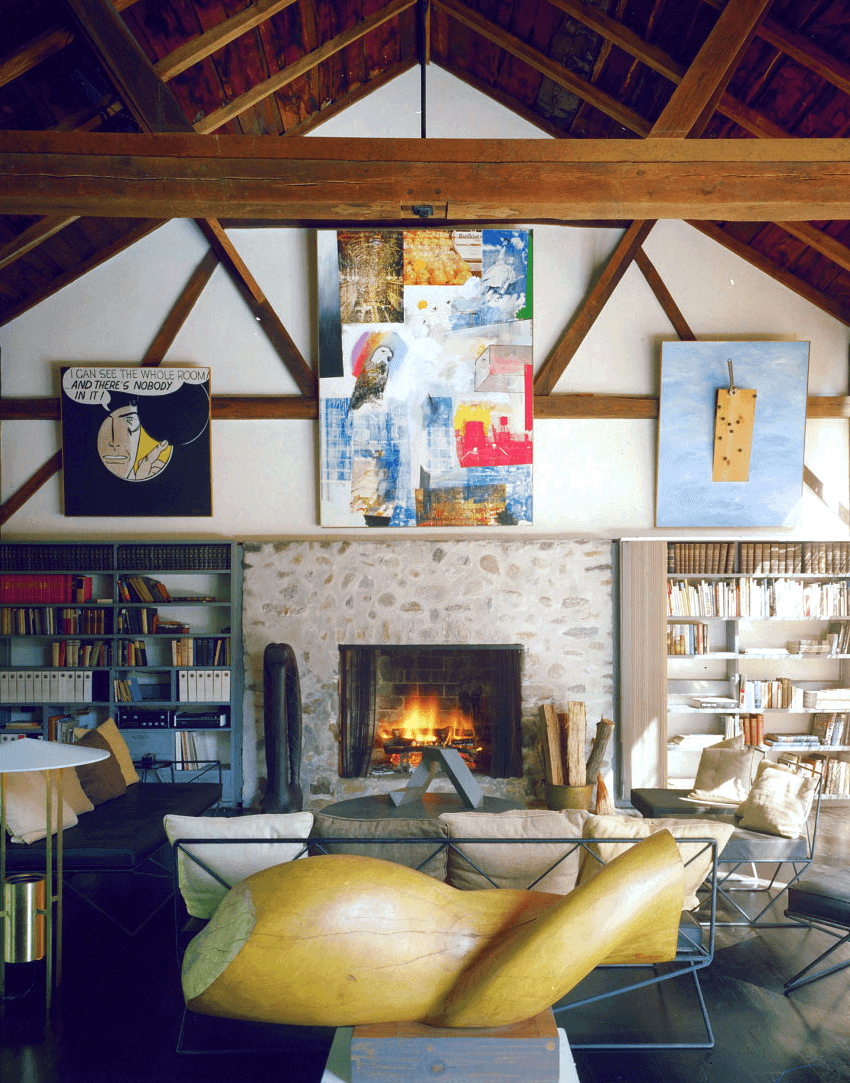

Robert Rauschenberg's Windward (center) in Tremaine barn at the Madison house, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While the city motif did not dominate the collection, it provided a unique cohesiveness. The motif first appeared in 1944 with the acquisition of Piet Mondrian’s incomparable Victory Boogie-Woogie, a geometric abstraction of a jubilating New York City alive with musical rhythm. Convinced that the painting was vital to the future of art, Tremaine made a lifelong effort to invite artists to see and study it. Jasper Johns recalled that when he was young Tremaine showed him Victory Boogie-Woogie and Premier Disque by Robert Delaunay. Initially, he was not impressed but then he changed his mind. “The Delaunay and the Mondrian became extraordinary paintings.”

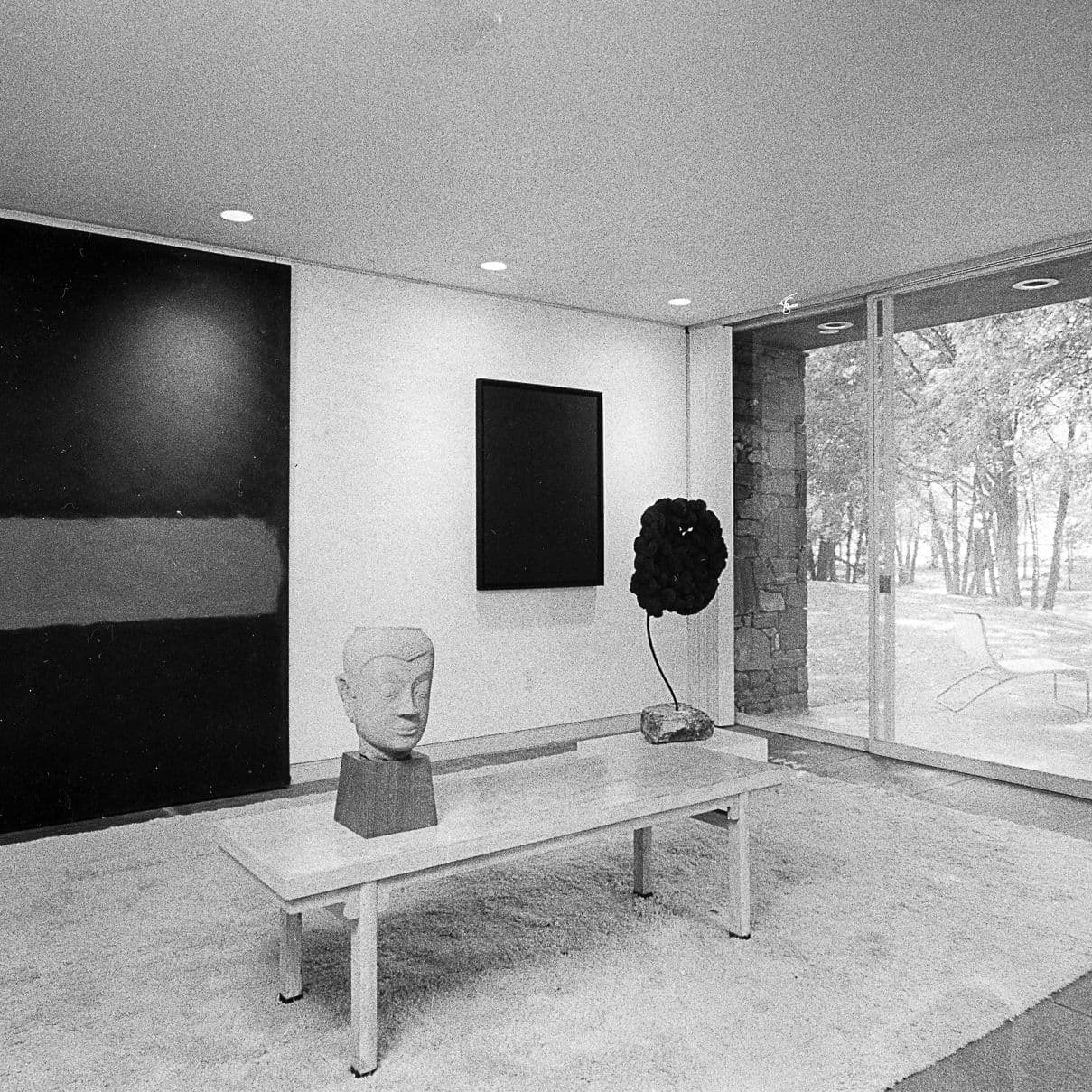

Premier Disque on the left and Victory Boogie-Woogie on the right in the The Tremaines' home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

When Mondrian arrived in New York City in 1940, he was entranced by the robust verticality of the skyscrapers as well as the city’s grid pattern with some streets in shadow while others were in sunlight. It was as if his artistic vision had become real. He felt free of the oppressive wartime fear that engulfed Europe. He also felt free of the great weight of European art and architectural history. Jean Arp who visited New York City in 1949 expressed the same feelings. “On my second visit, New York made a deep impression on me. It is a vast, wild city in which high-rises shoot into the sky like abundant tropical vegetation.”

Burton and Emily Tremaine shared that excitement. In a 1969 interview for Vogue Magazine with Gene Baro, a curator and art journalist, they spoke about returning from Europe and being struck by New York’s vitality. “They had arrived this way often, but this time they became particularly aware of the city, its glittering sprawl at a distance. It seemed a new, living thing, an embodiment of force. Later, as they drove toward midtown, the darting yellow taxis, the demanding billboards and throbbing neon seemed to them emblematic of a way of life. After the somberness of Europe, where they had just been, these things proclaimed America, her energy and directness.”

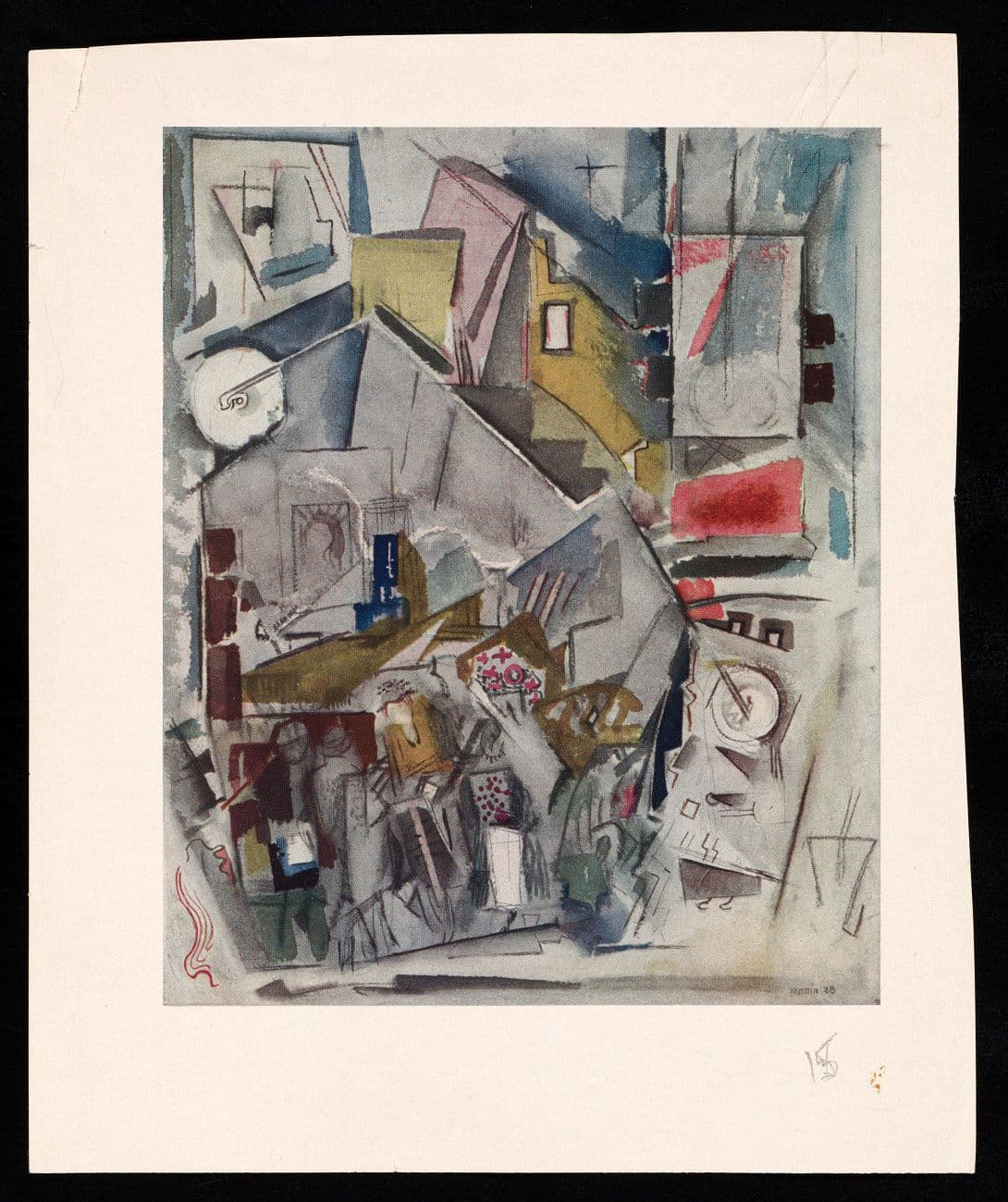

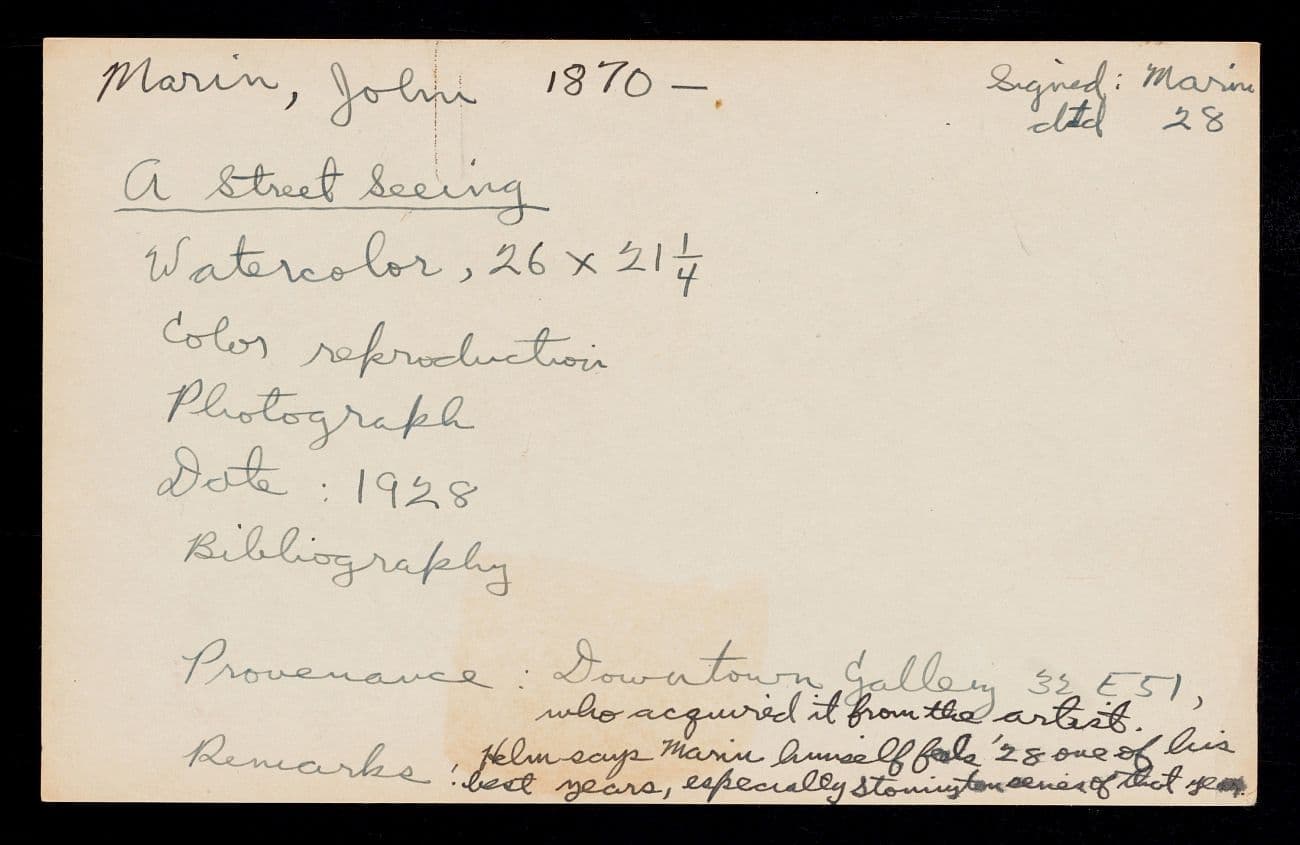

John Marin, A Street Seeing, 1928. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Tremaines also acquired John Marin’s A Street Seeing. Trained as an architect, Marin responded to the city’s complexity by painting skyscrapers, streets and bridges. The word “seeing” in the title, instead of A Street Scene, reversed the observer and the observed. As the art historian Mary Chalmers Rathbun wrote in the Painting Toward Architecture catalog, “The tension between large buildings and small, the tug-of-war between one mass and another, he translated into a compact personal idiom in his watercolors, concentrating in this frail medium the power and magnitude of the subject.”

From the Archives

From the Archives

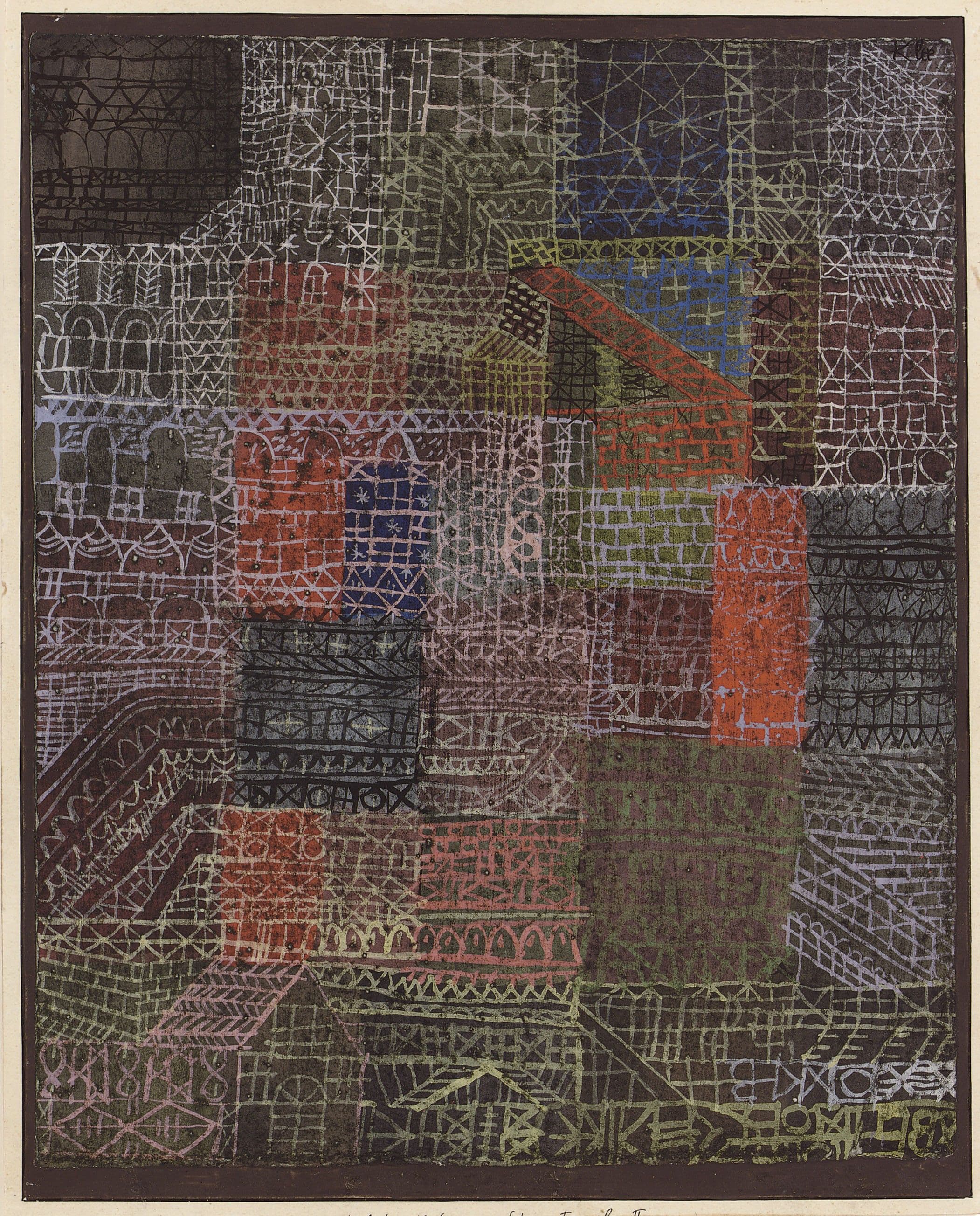

There was also Paul Klee’s Structural II. A teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany in the 1920s, Klee envisioned in the painting an overview of architecture from Germanic timber houses to a Moorish onion dome, connected by bridges and arches accentuated by night. Two other aspects of the city motif—darkness and stillness, point toward Tremaine herself, an enigmatic person whose connection with art was deep and spiritual. She often quoted Aristotle, “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things but their inward significance; for this and not the external mannerism and detail is their reality.”

Paul Klee, Structural II, 1924. Image in the public domain. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

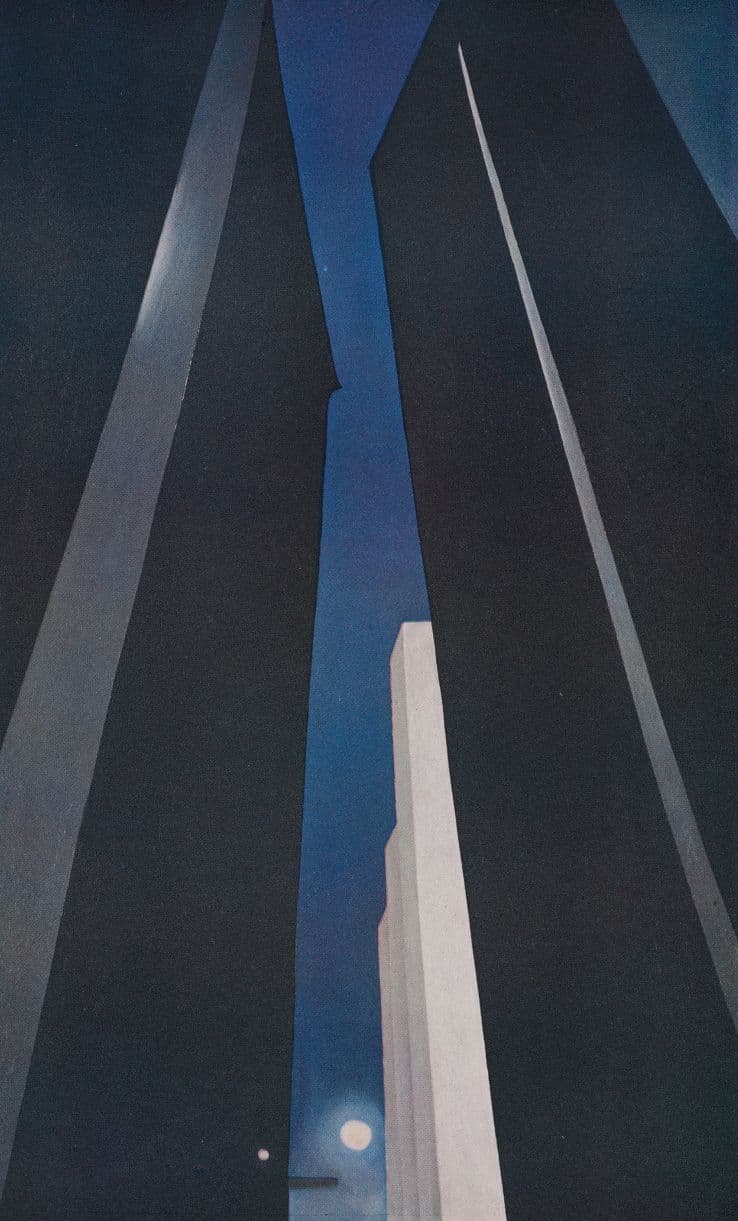

Over the years the Tremaines acquired many works that conveyed darkness and stillness, among them New York Night (aka City Night) by Georgia O’Keeffe with its soaring skyscrapers angling over an empty street lit by a single lamp. There was also the Moon Garden Series by Louise Nevelson that felt like a vast necropolis in moonlight. On a scrap of paper probably written in the 1950s, Nevelson jotted down several titles such as Portrait of a City at Night, Savage Majesty, Floating City, The City that Turned Black at Noon, and the City in the Sea. (See also “More Than the Sum of Its Parts: Louise Nevelson and Emily Hall Tremaine”.)

There was also Fragment for the Gates to Times Square by Chryssa with its blue neon lights within a Plexiglas box meant to be viewed after dark. In 1966, Chryssa completed The Gates to Times Square, a large work (12 x 12 feet) owned by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY. Then she created smaller works called fragments in which the neon blinked in unpredictable ways as if trying to send a message without anything to say. If city gates implied triumphal arches, then Chryssa’s fragments pointed to the diminishment of what once had been victorious.

Georgia O'Keeffe, New York Night, 1926. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

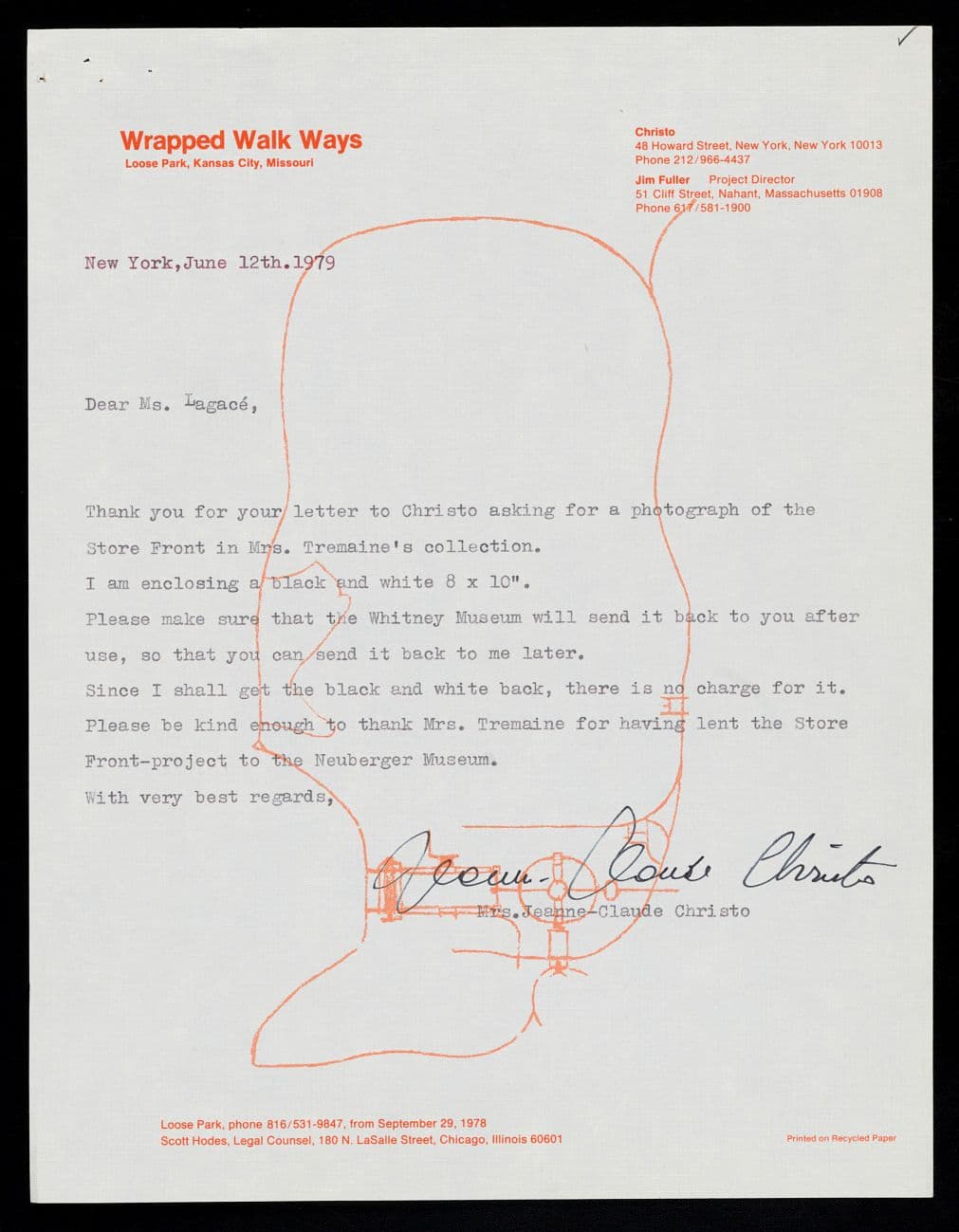

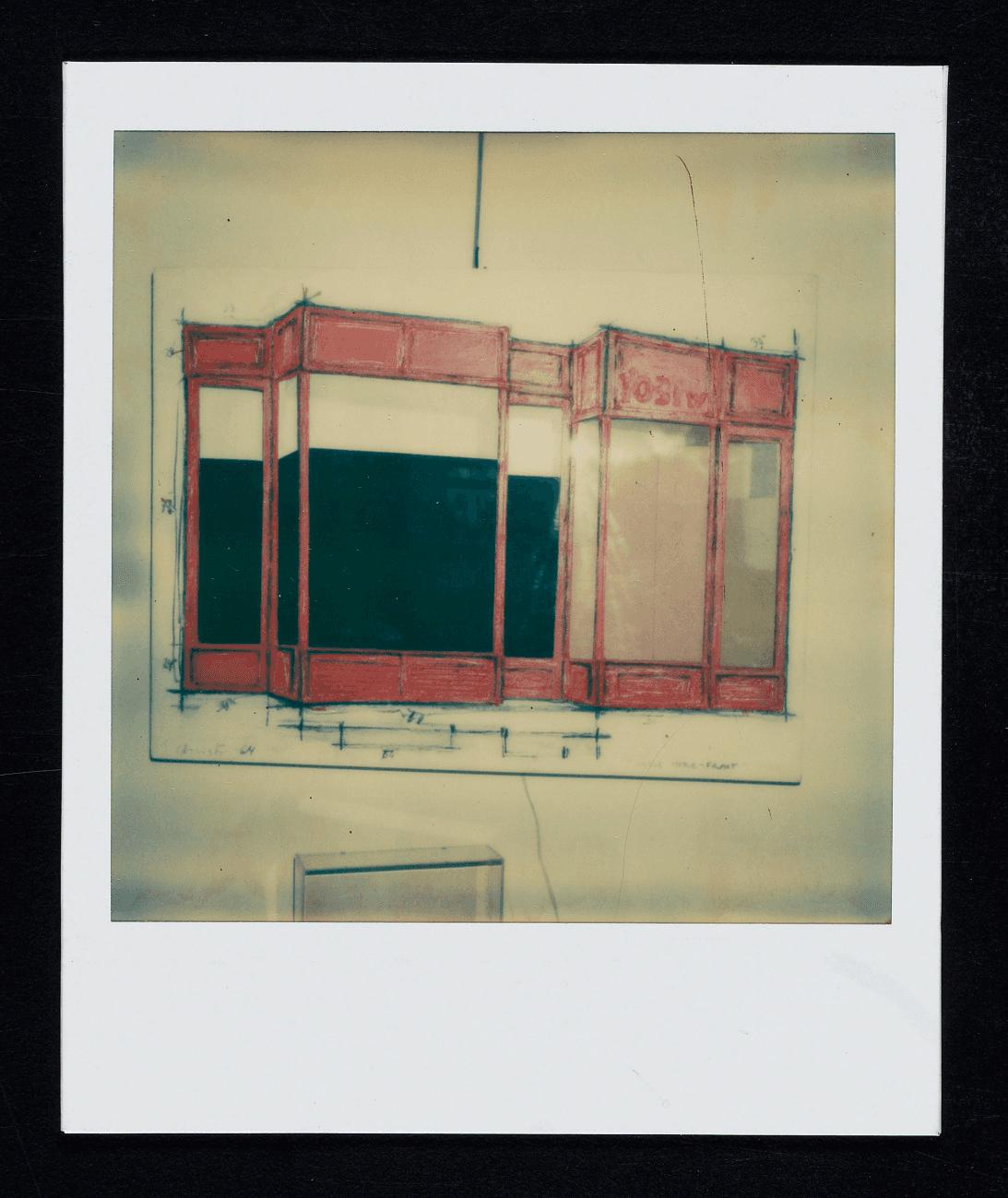

Polaroid, Christo, Double Store Front, 1964. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Then there was Double Store Front by Christo, which was dark, abandoned, and protruding. The Tremaines purchased it in 1964 not long after Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude arrived in America where their attention was drawn to abandoned buildings and the nature of transience. The red frame of the windows jutted out and was illuminated by bare light bulbs. One of the windows was covered in brown paper, presaging their later wrapped projects, while around the periphery were measurements and perspective lines. (See “Christo’s Art of the Hidden and Transient,” The Emily Files.)

Part of Tremaine’s attraction to pop art was the realization that the artists were awake to what they saw on the city streets.

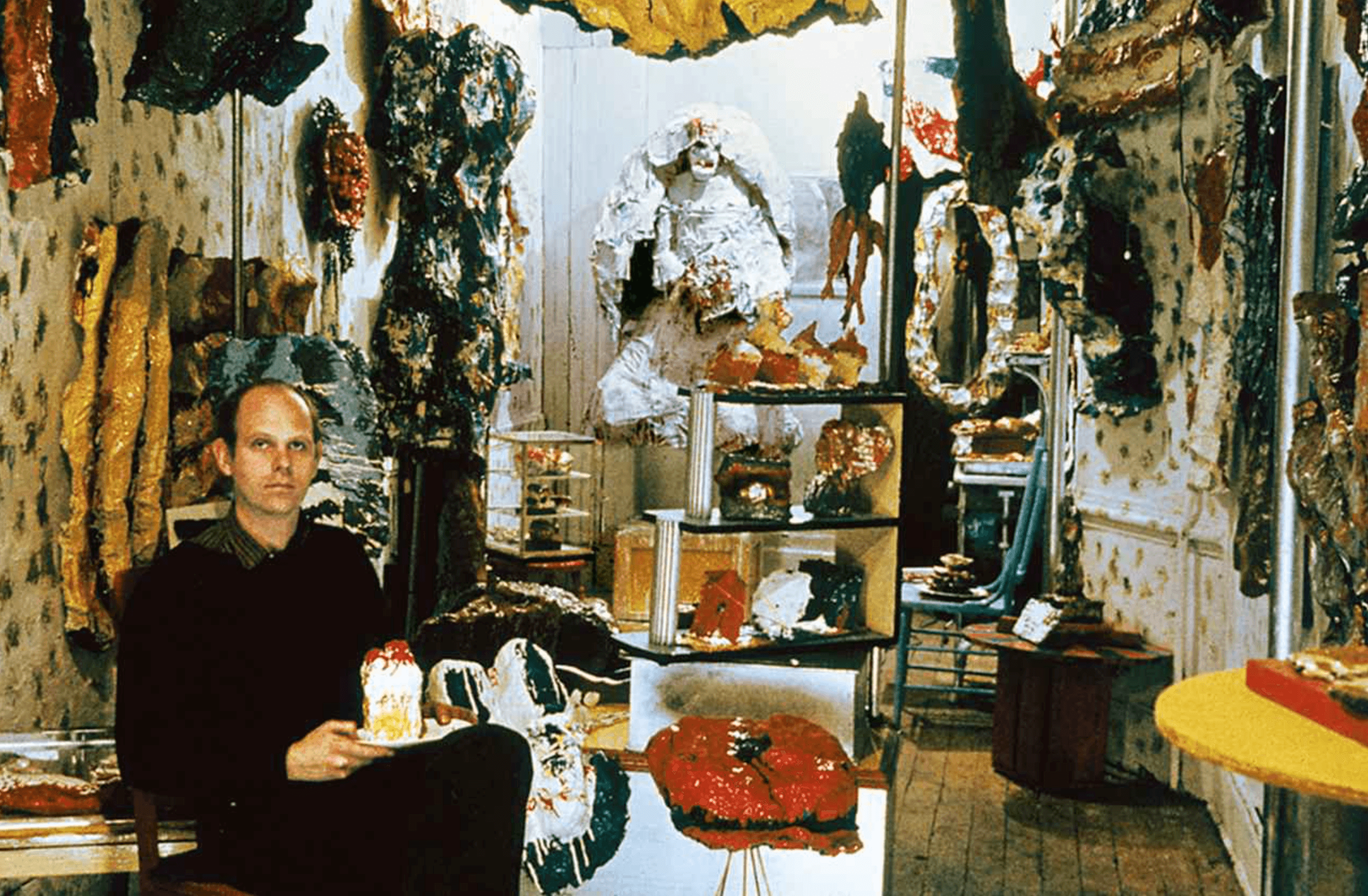

Yet all was not dark and foreboding. There was also the vibrant city in full thrumming daylight. Part of Tremaine’s attraction to pop art was the realization that the artists were awake to what they saw on the city streets. This began when she saw Claes Oldenburg’s 7-UP at the Green Gallery and decided she and Burton had to visit Oldenburg’s store-front studio. The taxi-driver dropped them off at the wrong location which led to an eye-opening stroll.

“We lost our way and looking for the address we walked through the whole-sale district where brides’ dresses are sold, and the windows were full of them. Then we turned a corner onto Second Avenue and as we walked up the avenue toward the street where Oldenburg had his store, we passed a mission on the roof of which was a cross and crown. We passed a restaurant with pies in the window. Just before we got to the store, there was a youngster with an improvised shoeshine stand. He had written out in pencil “fifteen cents.”

Claes Olderberg, The Store, 1961. Public Domain.

“They were about to close the gallery, and this big 7-Up was hanging there and I didn’t relate that to the soup cans at all, but I said, now this is very interesting, this is abstract expressionism, but this 7-Up is a very interesting comment on our vision.”

“The first thing we saw when we entered the Ray Gun Store was a bride made in the same plaster and enamel as the 7-UP we had seen at Dick Bellamy’s Green Gallery. There were also plaster cakes, pies and things that were in the window of the restaurant and the cross and crown we had seen on top of the mission, and I immediately remembered a collage I had seen at the Green Gallery in which Oldenburg had used the 7-UP, a piece of cake and a fifteen cent sign. Of course, I bought this collage as soon as I got back to the Green Gallery and I also bought the 7-UP plaster relief. Having gotten lost was, I am sure, a great help in showing us at once what was going on.”

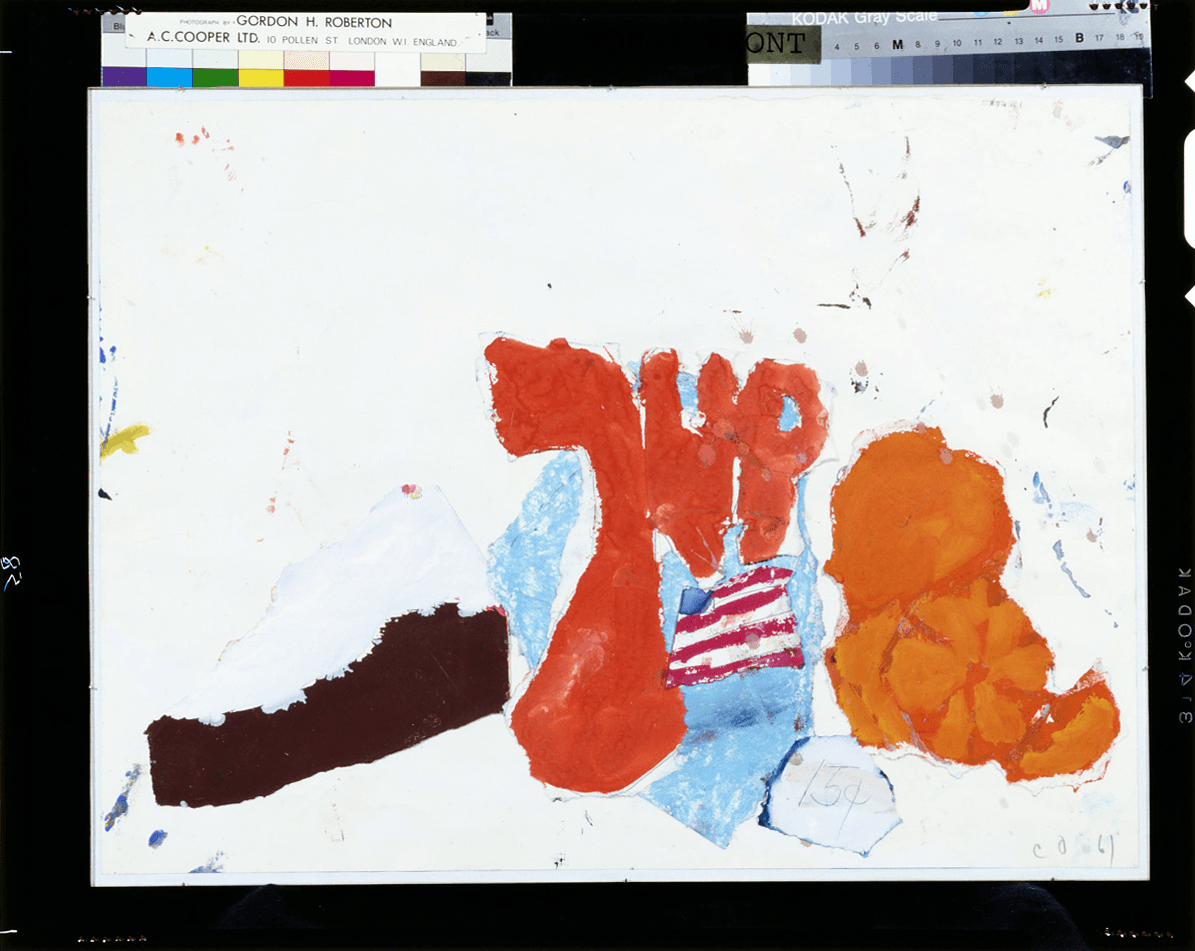

Claes Oldenberg, 7-Up with Cake, 1961. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

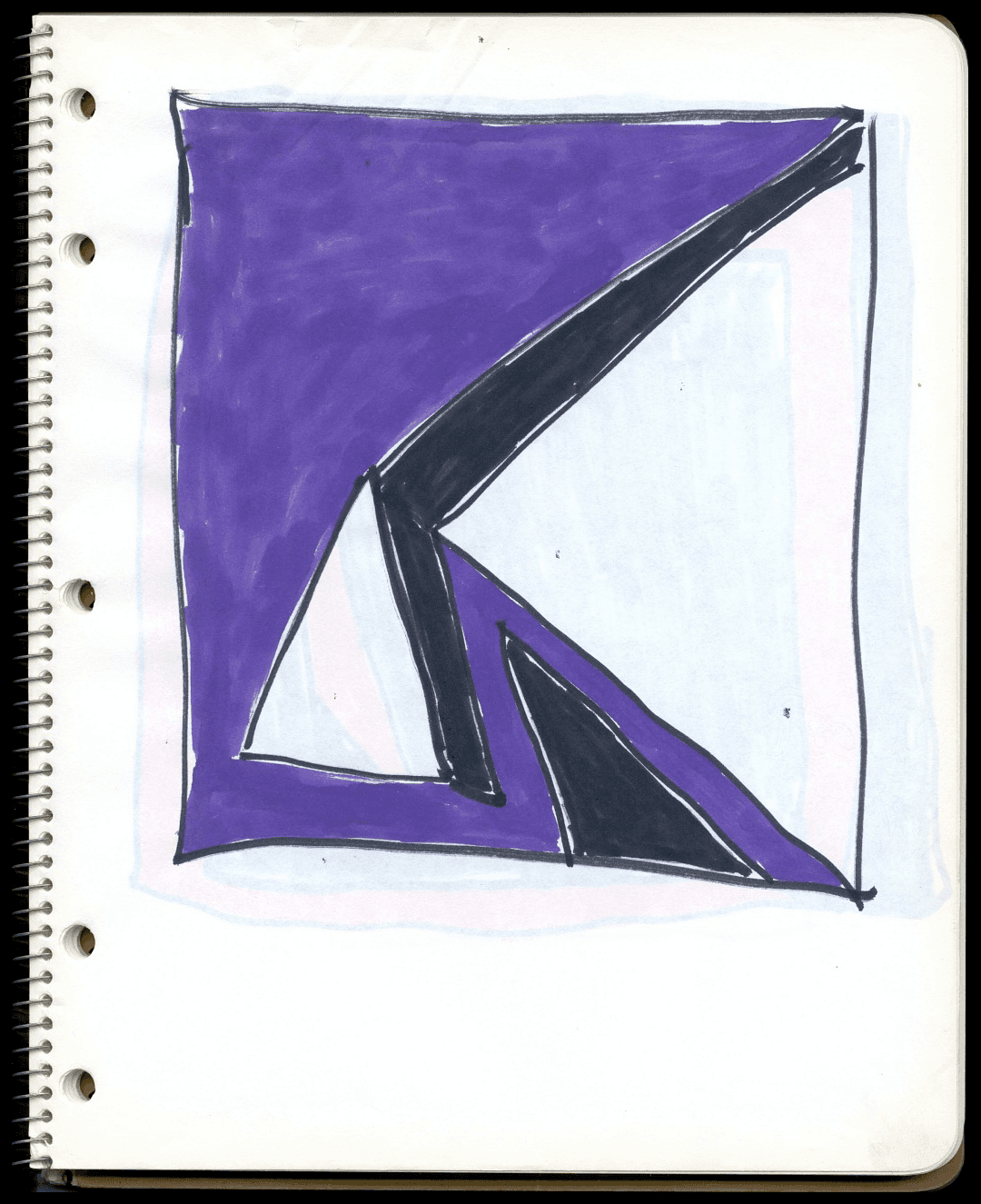

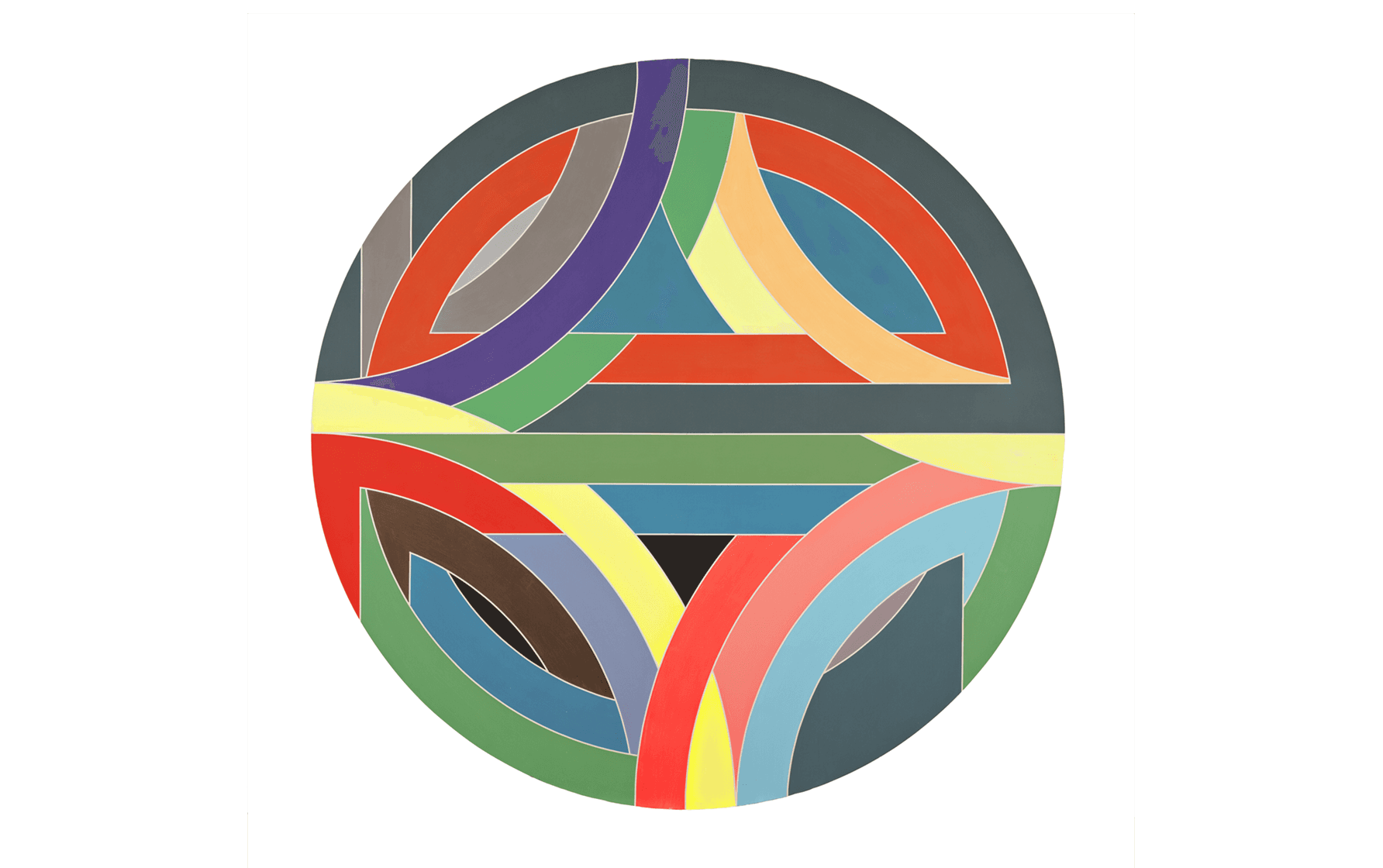

Sinjerli Variation IV by Frank Stella entered the collection in 1970. The name referred to a temple in an ancient Mesopotamian city, yet the painting also hinted at the intricacy of Islamic art. A large tondo ten feet in diameter, when it was exhibited at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut it was given its own wall to which it drew all eyes. While conjuring up the circular layout of a city, it also had about it the energy of an urban traffic circle with roads entering and exiting. If Nevelson’s Moon Garden suggested a city in darkness, Stella’s suggested a city in fluorescence.

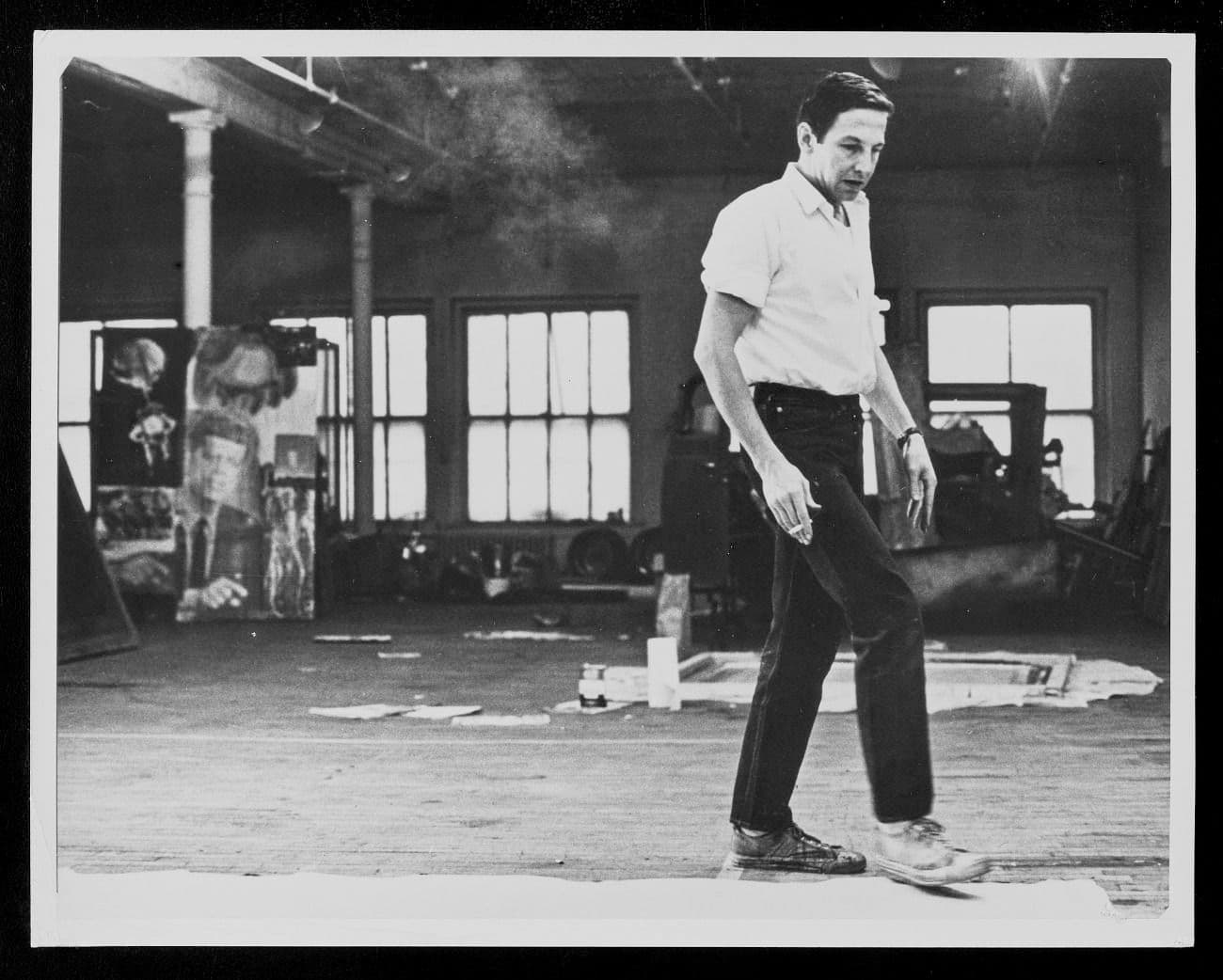

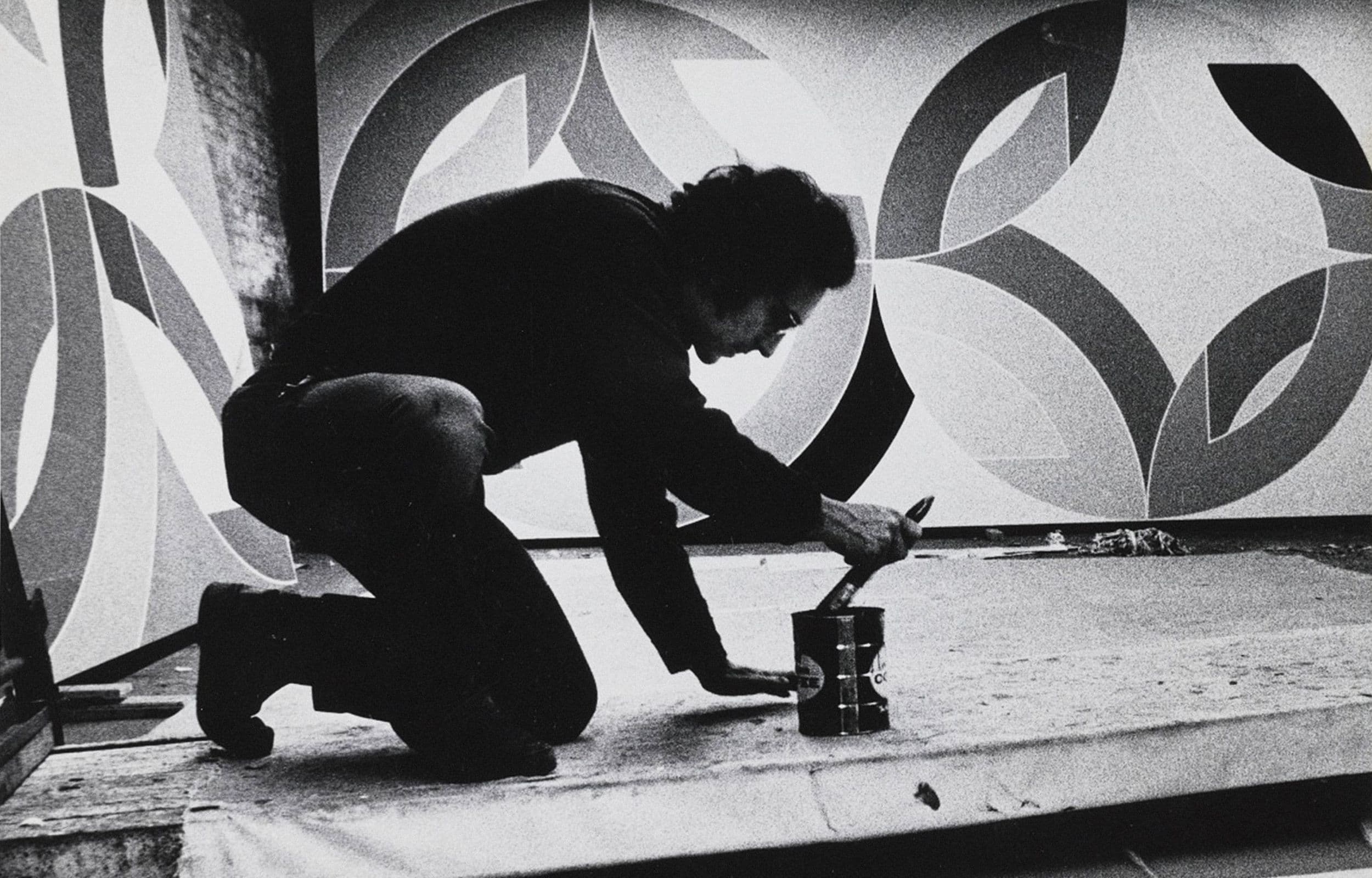

Frank Stella in his studio.

Background: Frank Stella in his studio. Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Foreground: Frank Stella, Sinjerli Variation IV, 1968. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, and partial gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Sr., 1982.157. © Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1984 the Tremaines acquired Venus by the graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Always on the lookout for new talent, Tremaine turned her attention to the work of 24-year-old Basquiat. An anatomical female torso, a building labeled “the great circle,” geometrical diagrams, scribbled words such as radium and asbestos, a waving dark figure—all added up to an edgy urban world. (See The Emily Files, “Graffiti Art, Detritus, and Social Provocation.”)

As Venus makes clear, the city motif was both positive and negative. Even in seemingly optimistic and patriotic works in the collection there was often a mordant quality. For example, Rauschenberg’s Windward showed broken windows, smokestacks, and dripped paint that occluded the Statue of Liberty as if in a cloud of smoke. Ultimately the city’s bright and dark aspects merged, with darkness splintered by light, and light fractured by darkness.

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: Trikosko, Marion S, photographer. Skyscrapers at night New York City / MST. New York, 1967.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.