About

Tremaine Timeline

Emily Hall Tremaine and her husband, Burton G. Tremaine, Sr., were collectors of 20th-century art with an emphasis on work done by artists after 1945. Their collection of more than 700 works was of such quality and scope that it embodied some of the best paintings of the century. Artists in their collection included Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg. At the time the Tremaines began to purchase their works, these innovative artists were not yet recognized by the art world.

The timeline that follows includes major events and the acquisition of selected works.

1901: Burton Gad Tremaine was born on August 31 in Cleveland, OH, to Burton Gad Tremaine, known as B.G., and Maude Tremaine. That year B.G. founded the National Electric Lamp Association (NELA).

1908: Emily Hall was born on January 31 in Butte, MT to William Hubbard Hall and Purdon Smith Hall. Purdon’s father was the founder of the S. Morgan Smith Co. in York, PA, which manufactured hydroelectric turbines. Hall was a dentist who invested in mining and mining supply.

Emily only spent the first nine years of her life in Butte, Montana, yet the place left its mark on her and helped shape her artistic perceptions.

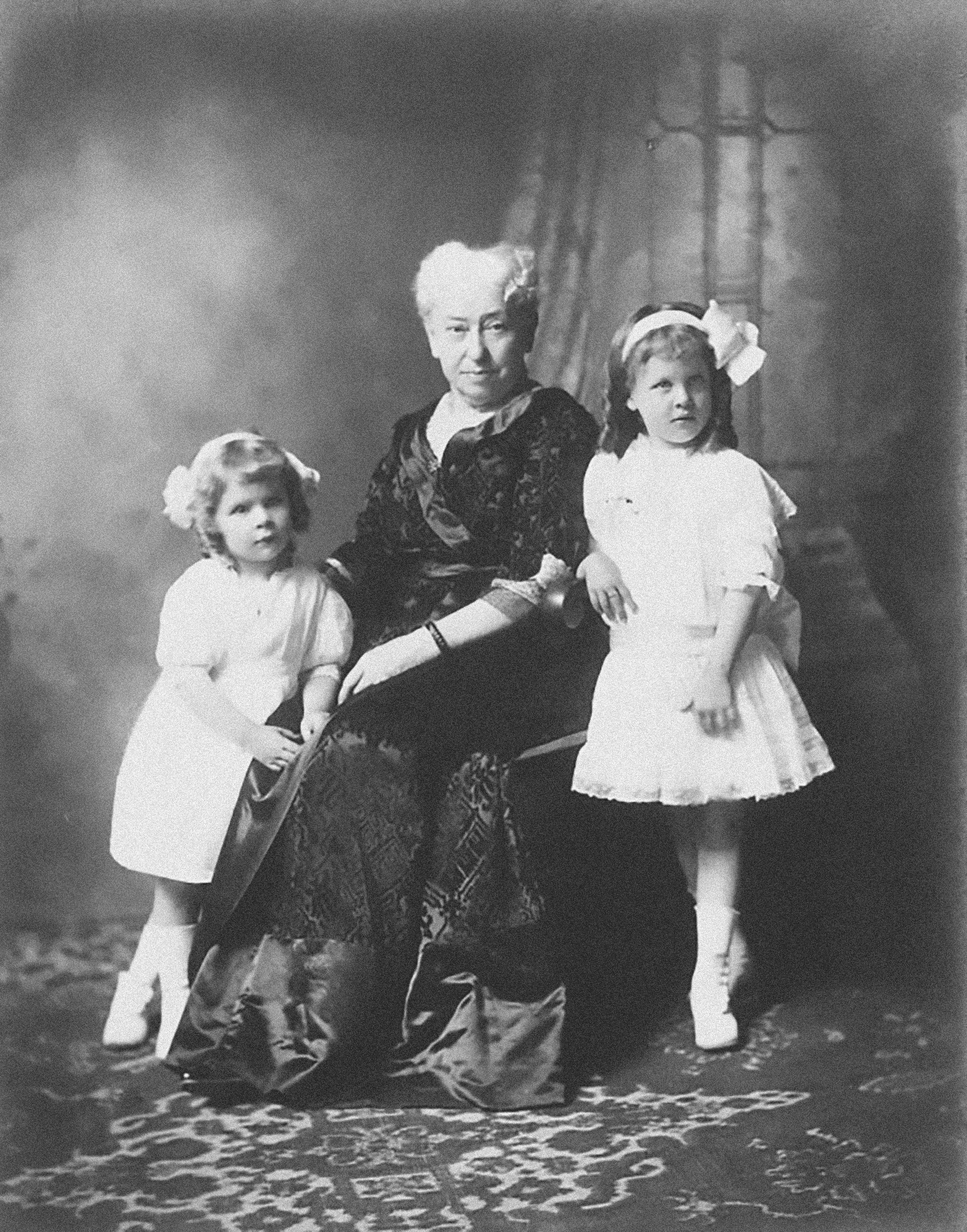

Emily Hall with her sister Jane Hall and Emma Smith, 1911. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

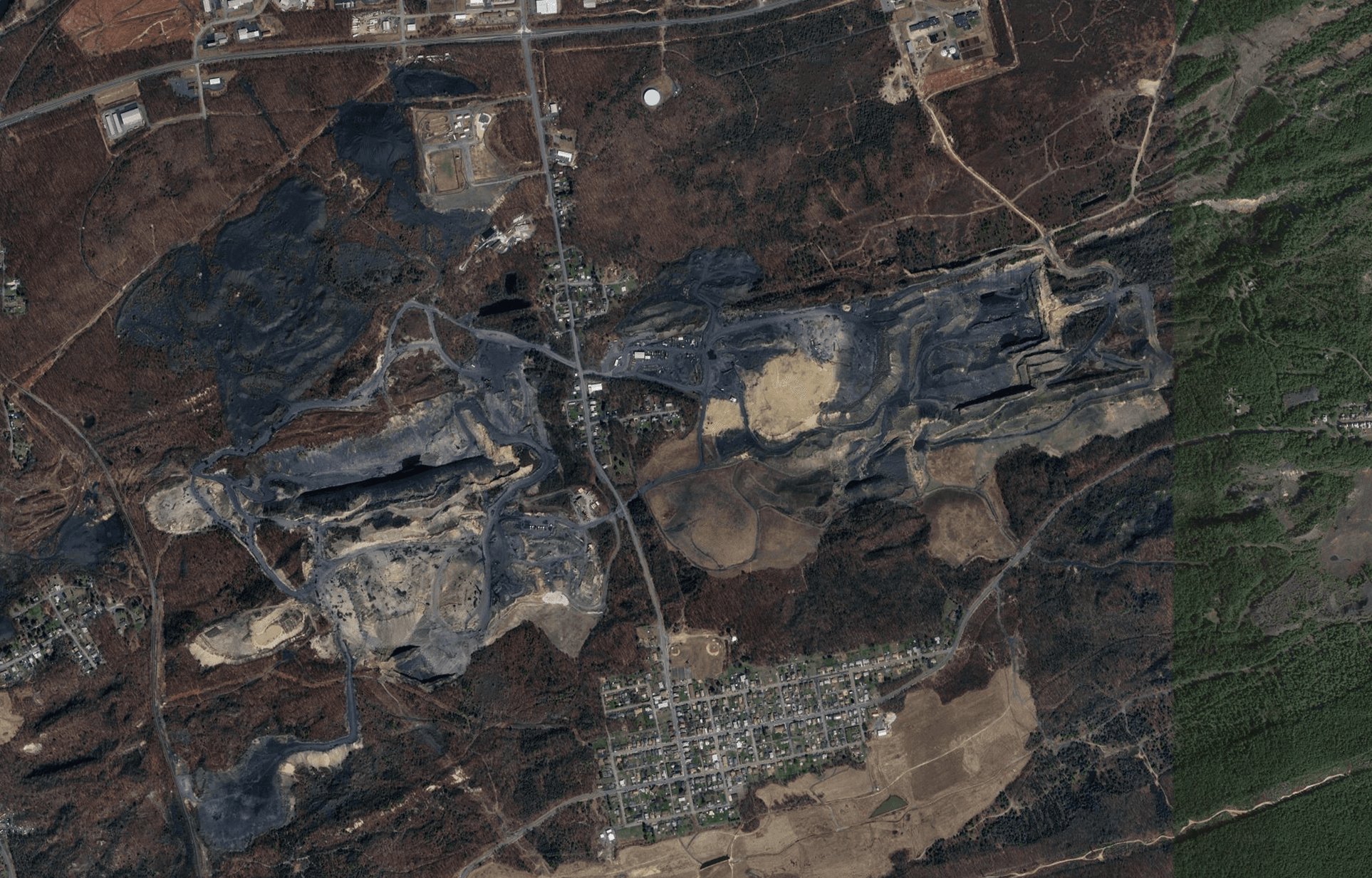

More than forty years later, Emily came to own the overpowering canvas by Franz Kline called Lehigh (1956).

Starkly black and white, it depicted the equally devastated coal mining fields of Pennsylvania by means of jagged, raw brush strokes.

Image 1: Franz Kline, Lehigh, 1956. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image 2: Coal mining field in Pennsylvania. Map data: Google, Airbus.

1912: B.G. and his partners constructed NELA Park in Cleveland, OH. With trees, gardens, and amenities for employees, it was the first industrial park in the U.S. NELA was eventually taken over by General Electric, which had been its chief financial backer, becoming GE’s lighting division. B.G. served on the board of directors.

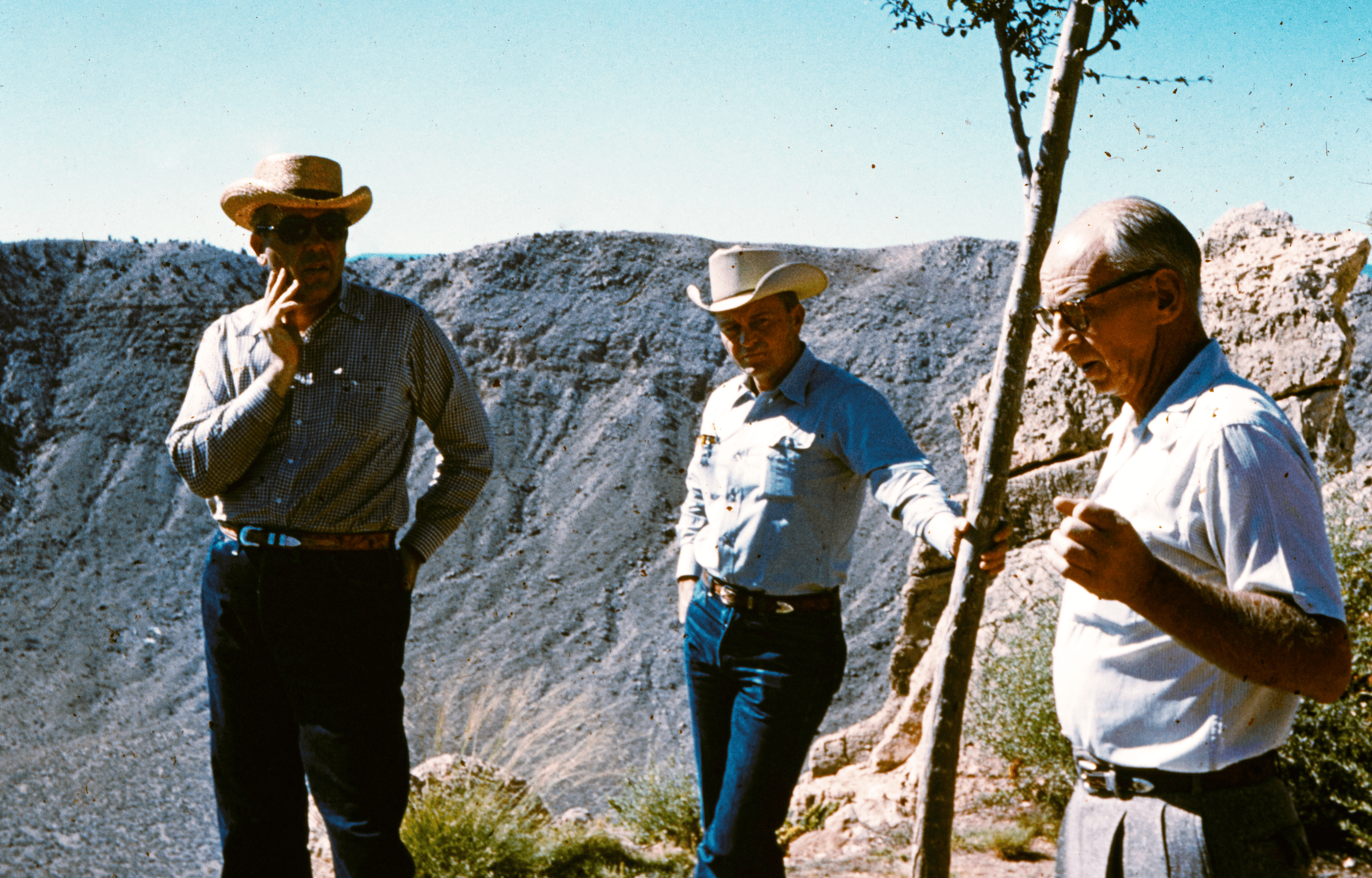

1919: B.G. purchased a 320-acre ranch near Chandler, AZ. Over a 20-year period, acquisitions brought the acreage to 330,000, including the rights to Meteor Crater, a natural wonder that would become a well-known tourist destination. When the Bar T Bar Ranch was acquired in 1930, the name was used for the entire property. B.G. initiated a lucrative milling process for alfalfa and oversaw a large cattle operation with the help of his business partners.

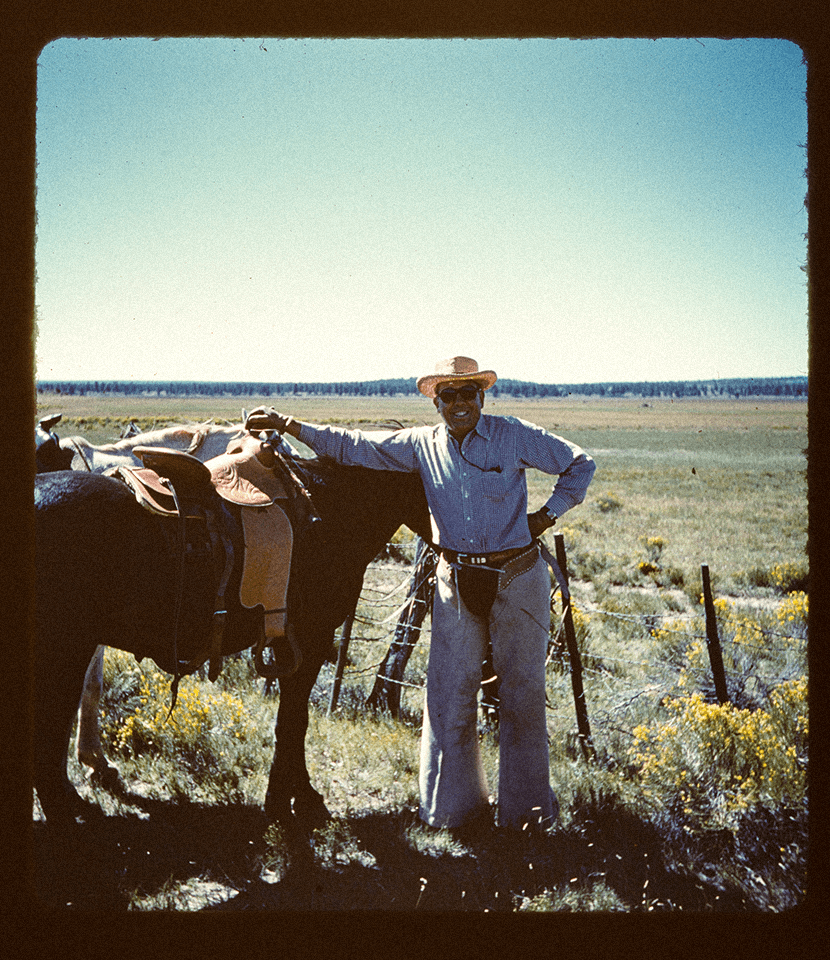

Burton Tremaine at Bar T Bar ranch. Image courtesy of the Tremaine family.

1920: Burton Gad Tremaine (then known as Junior) married Dorothy Chapman in Cleveland, OH. They had two children Burton Gad Tremaine (who would take on the Junior suffix) and Dorothy (known as Dee) Tremaine.

1924: The Halls moved from Butte, MT to Montecito, CA. During this period, they traveled extensively in Europe, often visiting art museums.

GE purchased The Edward Miller Company in Meriden, CT and sold it to B.G. Tremaine and his partner. The company had started in 1844 making whale oil lamps.

1927: Emily Hall met 16-year-old Baron Maximilian von Romberg while both families were touring through Egypt. Born in Wiesbaden, Germany, on March 7, 1911, Max was the son of Antoinette Converse of Boston, MA and Baron Maximilian von Romberg of Wiesbaden, Germany. Three years after Max’s birth, his father, a German officer, was killed in World War I.

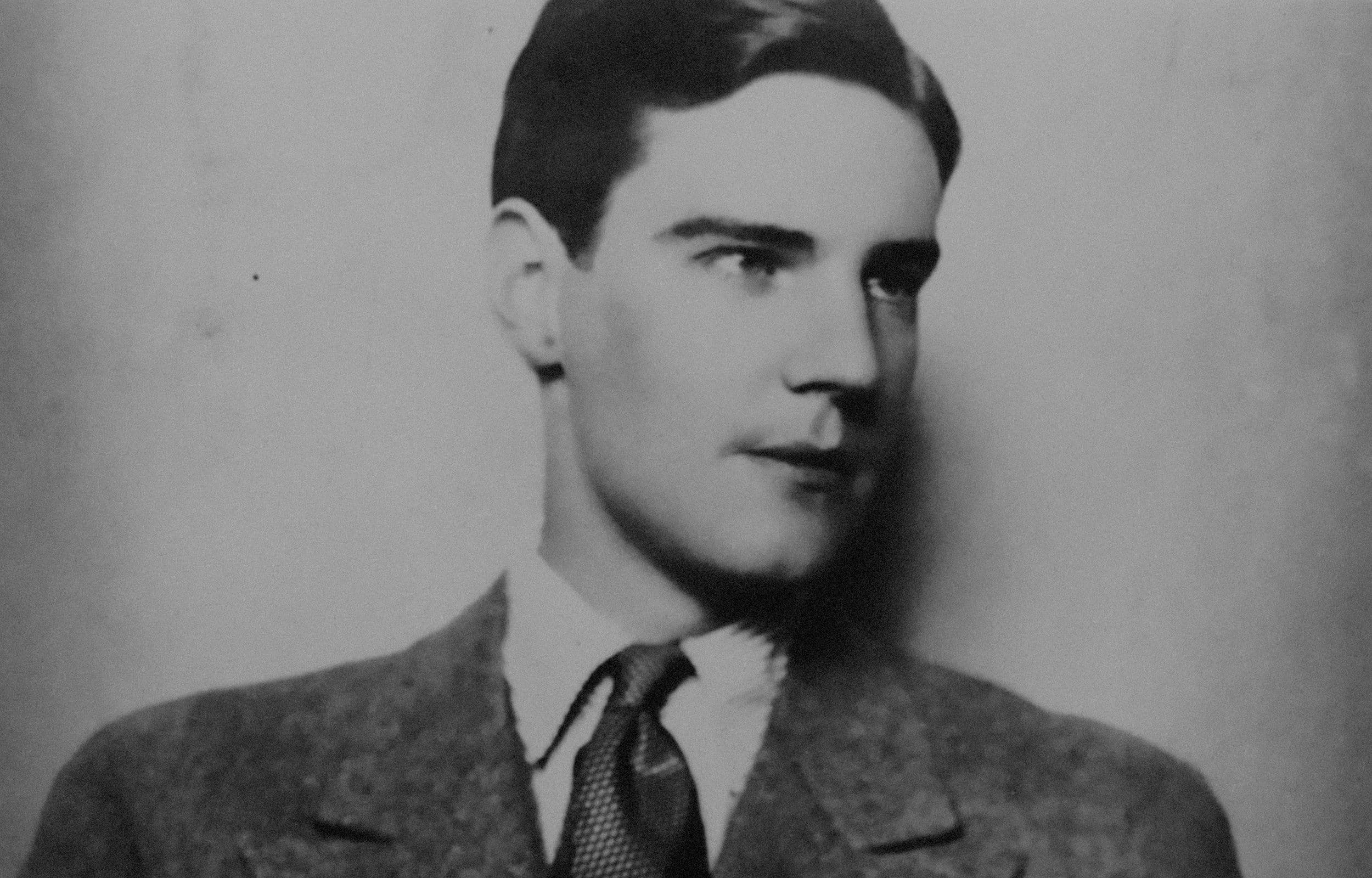

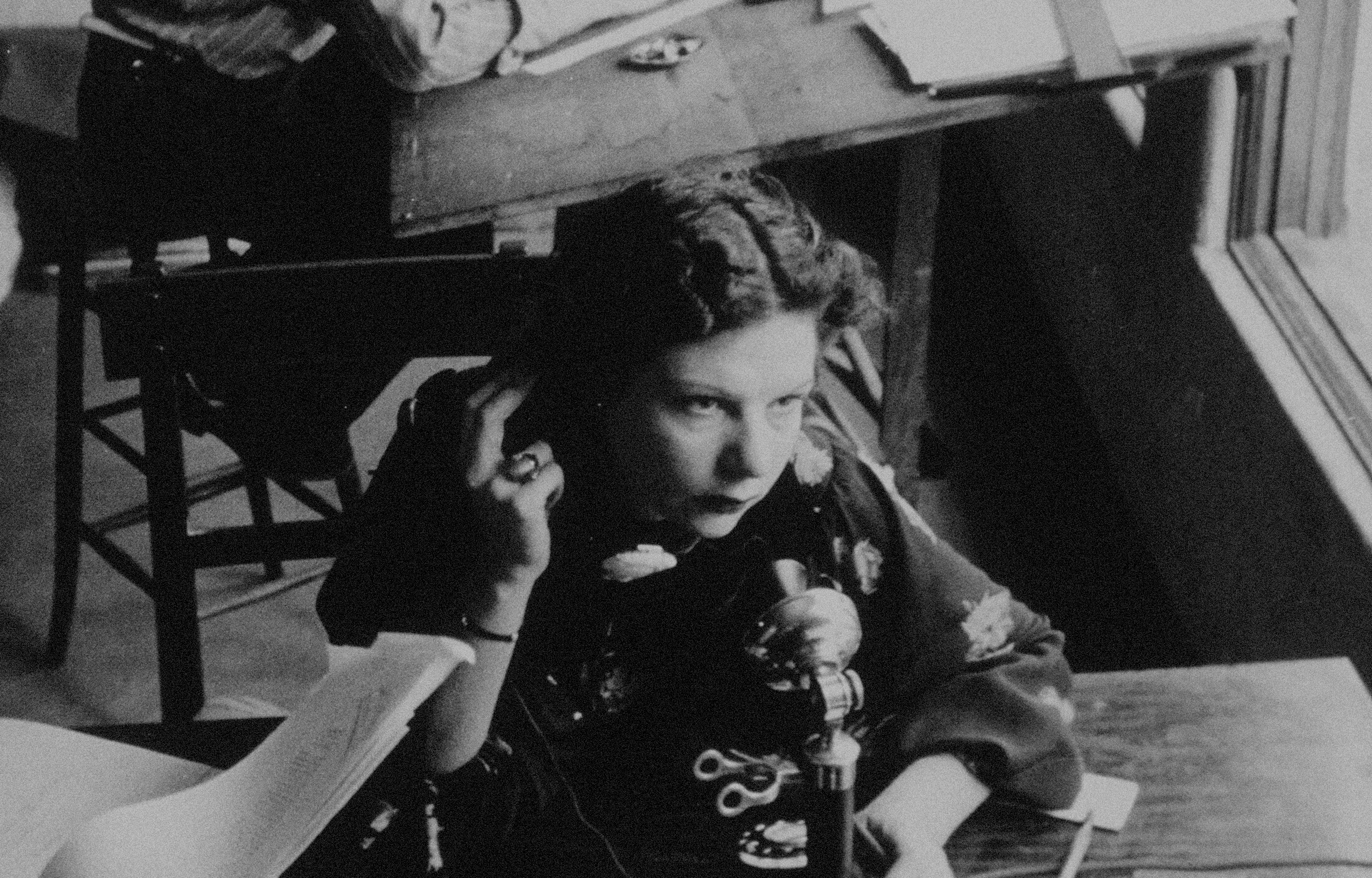

In 1927 at a coming-out party given by her parents, the beautiful nineteen-year-old debutante with dark, curly hair and soulful eyes was introduced to a German baron named Maximilian Edmund Hugo Wilhelm von Romberg. Sixteen years old, he was extremely handsome with brown hair that he wore slicked back, blue eyes, and a chiseled profile that deserved to be minted into a coin. He was trained in the sports of European nobility—riding and fencing—yet was thoroughly American in his love of everything fast and dangerous.

Emily Hall von Romberg, circa 1920s–1930s. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

1928: Emily Hall and Baron Maximilian von Romberg were married on April 14 in New York City. They lived in Montecito.

1930: William Hubbard Hall, Emily’s father, died on March 19 in New York City at the age of 74.

1931: B.G. Tremaine appointed his son Burton as president of The Miller Company. Burton had been an executive of Superior Screw and Bolt, a company owned by his father in Cleveland, which was sold at a profit in 1928.

1933: In April, Emily filed for divorce from Max, but then they reconciled.

1935: Emily left Max again, but they reconciled after he was in a serious automobile accident.

Emily launched a monthly society magazine titled Apéritif, which ceased publication in 1936.

1936: Emily purchased The Black Rose by Georges Braque, her first major acquisition, marking the start of her focus on twentieth-century art.

Emily explained, “After a while, I decided I was really going to be brave and buy a picture which I loved and could not get out of my thought.” Her choice was Georges Braque’s The Black Rose (1927). Braque himself considered The Black Rose to be the triumph of one of his most creative years in painting.

Behind all great art collectors there is usually an eminence grise (whether a dealer, another collector, or an artist) who provides expert advice and guidance, thereby influencing the nature of the collection. When Emily first started collecting in the 1930s, her eminence grise was her close friend and relative A. Everett Austin, Jr. (Chick), director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, whose help she readily acknowledged and deeply appreciated. “I think Chick actually had more influence on me and the kind of direction our collection was taking than anyone.”

Whenever she analyzed the factors that led her towards art in the 1930s, Emily included her interest in philosophy, frequently quoting Aristotle: “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance; for this and not the external mannerism and detail is their reality.”

1937

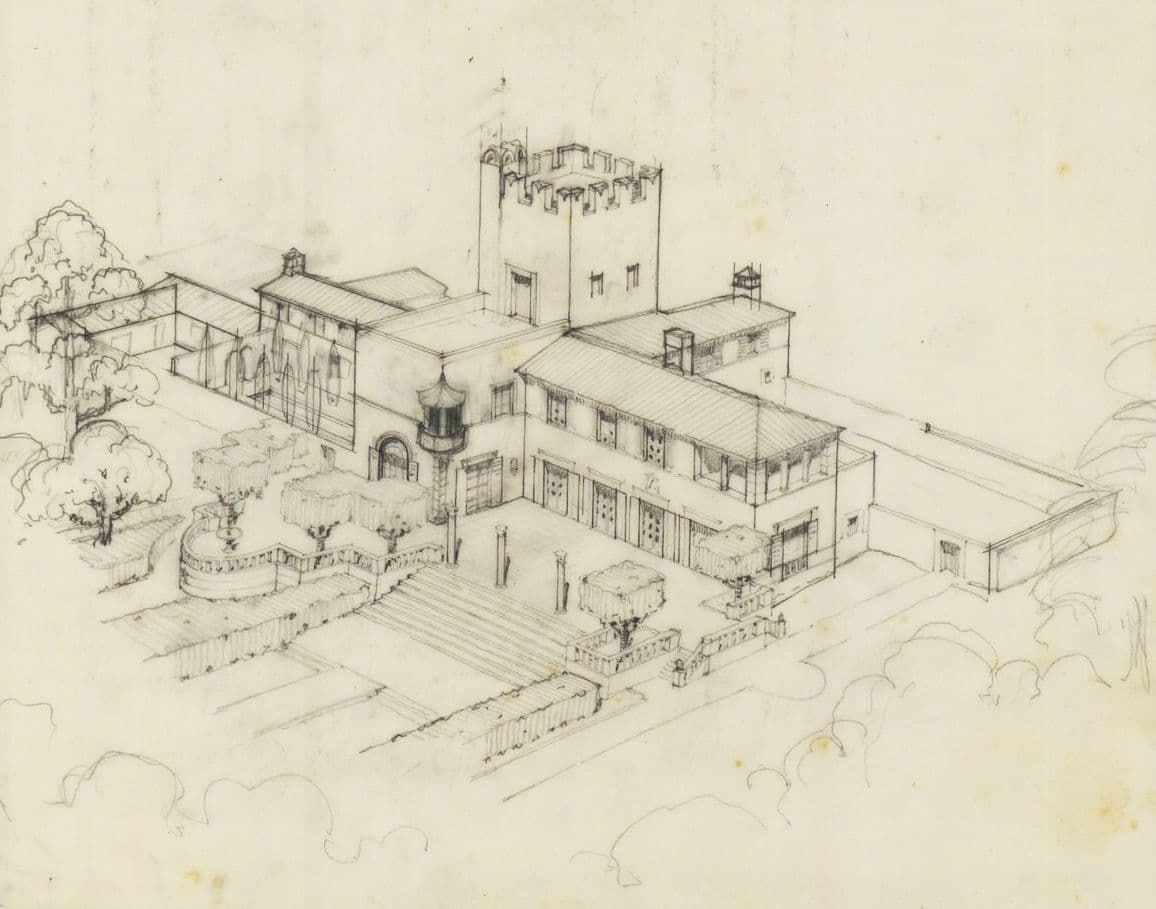

Emily and Max hired the architect Lutah Maria Riggs to design a home in Montecito to be called Brünninghausen.

Image 1: Georges Braque, The Black Rose, 1927. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Image 2: Chick Austin. Image courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum. Image 3: Emily Hall Tremaine. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Image 4: The renderings of the exterior, details, and sections of the Von Romberg house also show how the exterior changed as Riggs and Emily Von Romberg worked together to create a house that would suit all involved. Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara. Image 5: Lutah Maria Riggs (American, 1896–1984), “Brünninghausen,” Montecito, California. Partial view of the completed building, circa 1938. Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

1938: Max was killed on June 4 when his airplane crashed on an overcast morning near the airport in Red Bank, NJ. A month later, Brünninghausen was completed.

Divorced from his first wife, Burton Tremaine married Sally Ondeck Wylie who owned a house and property in Madison, CT.

1939: On August 10, Emily married Adolph Spreckels, heir to a fortune made in the sugar industry.

1940: Emily left Spreckels in August and subsequently filed for divorce but then for unknown reasons withdrew the filing.

1941: Purdon Smith Hall, Emily’s mother, died on December 26.

1942: Emily filed for divorce a second time but had difficulty serving papers because Spreckels could not be located.

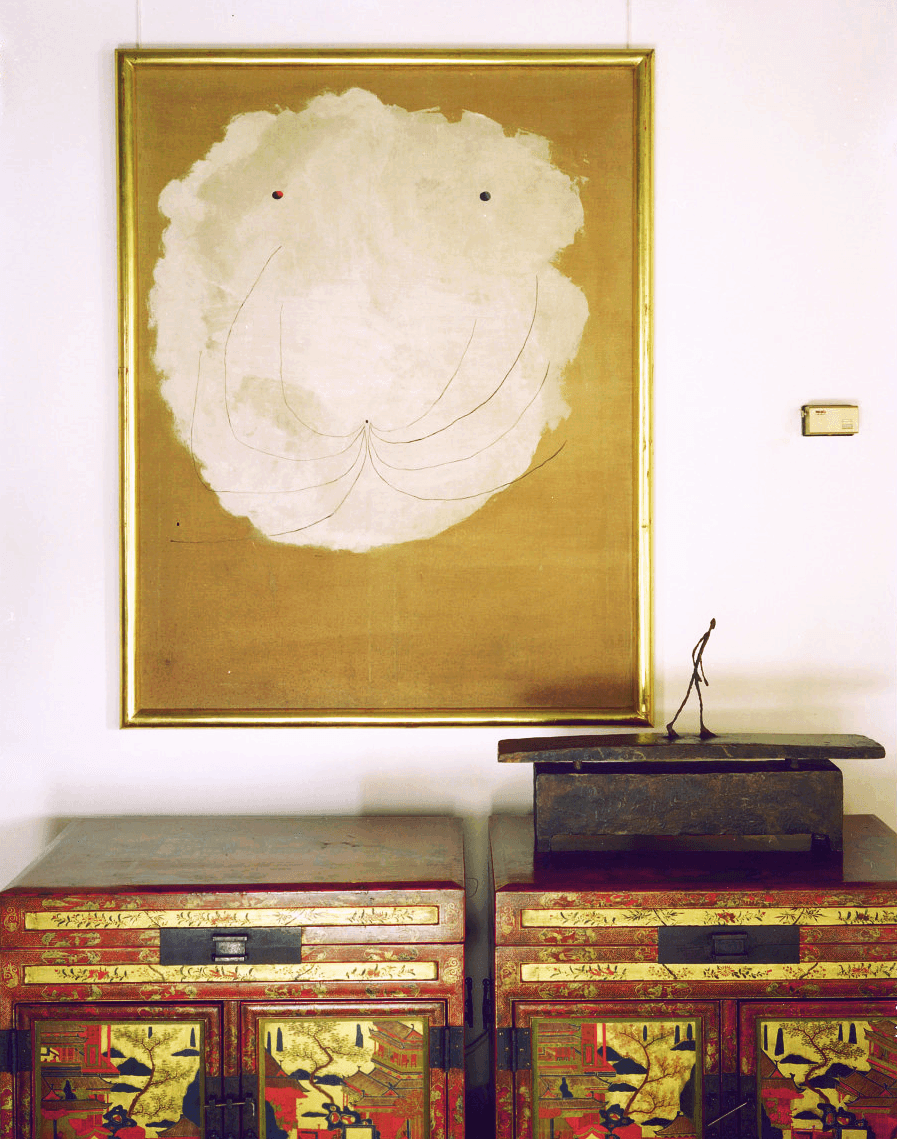

Acquired Le Chat Blanc by Joan Miró, which was painted in a form of surrealism.

Joan Miró, Le Chat Blanc on the wall of the Tremaines' home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

1943: Burton and Sally Ondeck Wiley Tremaine divorced. Burton became owner of the Madison property. He purchased additional parcels of land bringing the total to 76 acres.

1944: Emily met Burton through his brother and sister-in-law Warren and Kit Tremaine who lived in Montecito. Residing at Brünninghausen, she also maintained an apartment in New York City.

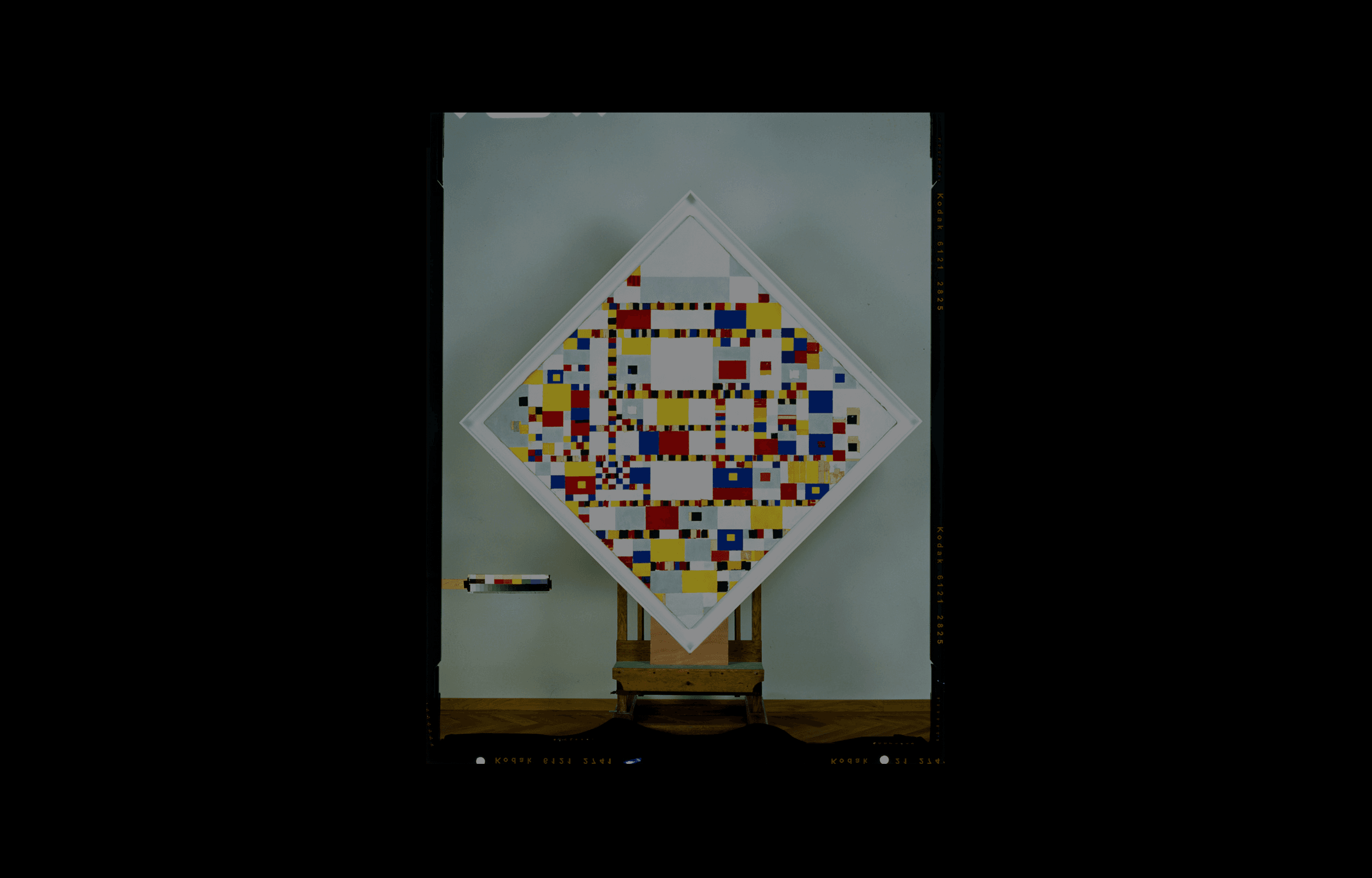

Beginning in 1944, Emily shifted her focus to New York City, where she began to concentrate on art collecting. During the six-month period before her marriage to Burton, Emily acquired masterpieces by several well-known Europeans including Piet Mondrian, Joan Miró, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky.

Following the war, it was a perfect time for the Tremaines to collect art. Besides her visual acuity, Emily had the ability to analyze what she heard and read; Burton had the gut instinct; they both had the means; and the art world had shifted from neutral into high gear, with New York City as its base of operations instead of Paris, although the importance of that shift would only be revealed in hindsight.

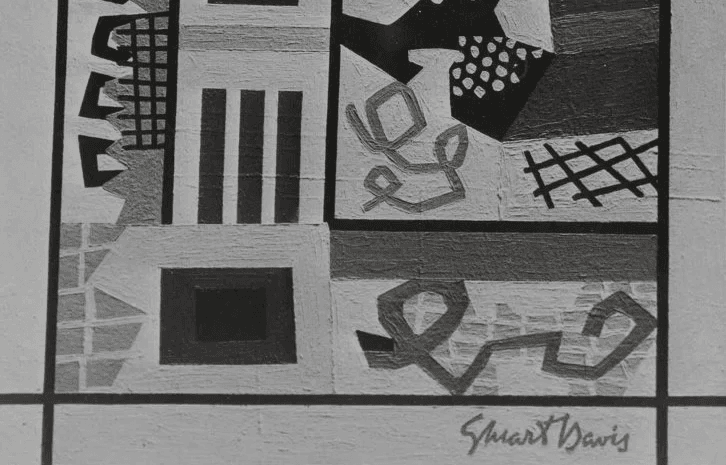

Then, as if to prove decisively that her days as a novice collector were over, she acquired the works of a number of highly talented but lesser known American artists, including Stuart Davis, Milton Avery, Harry Bertoia, and Ralston Crawford.

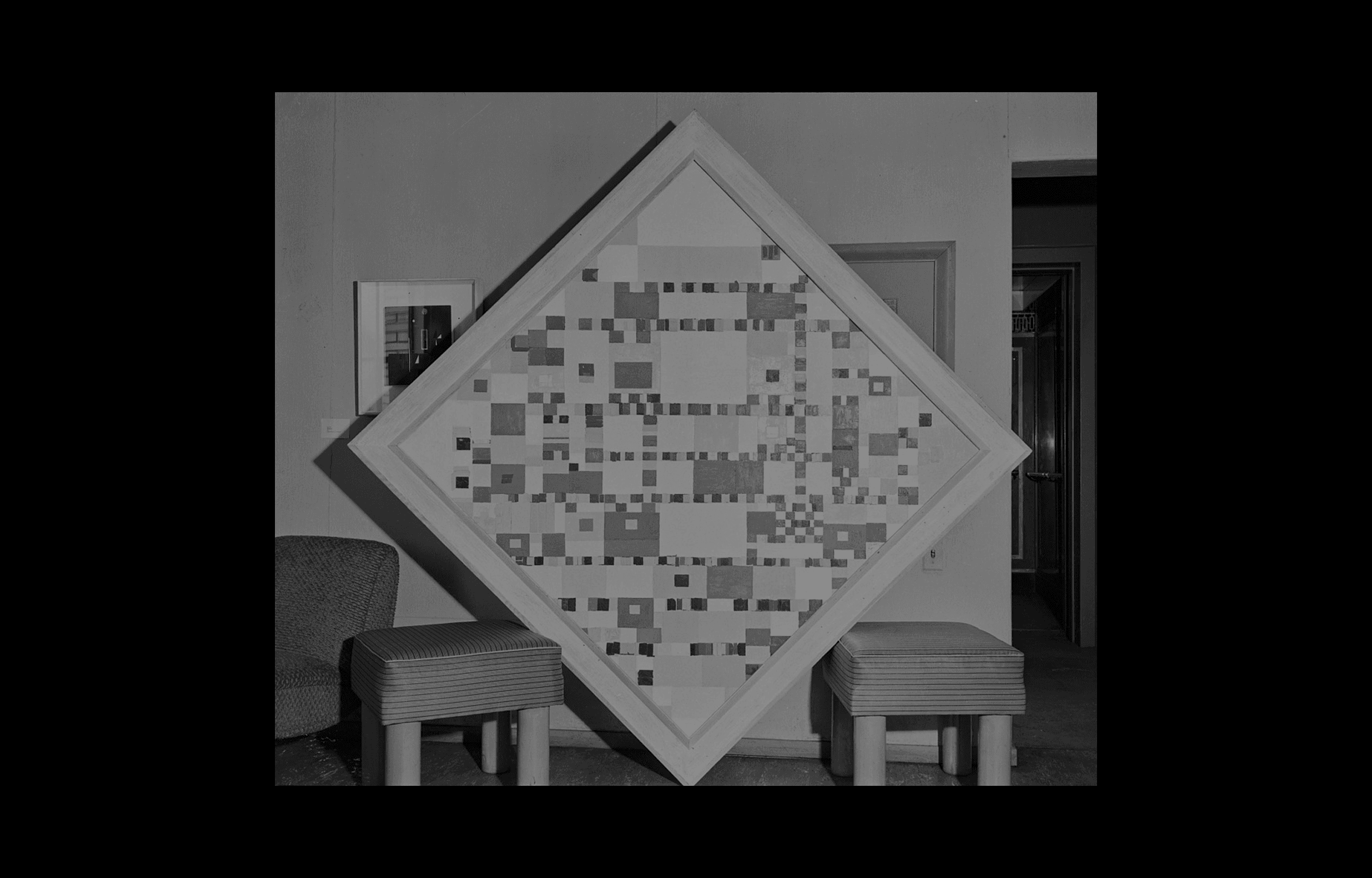

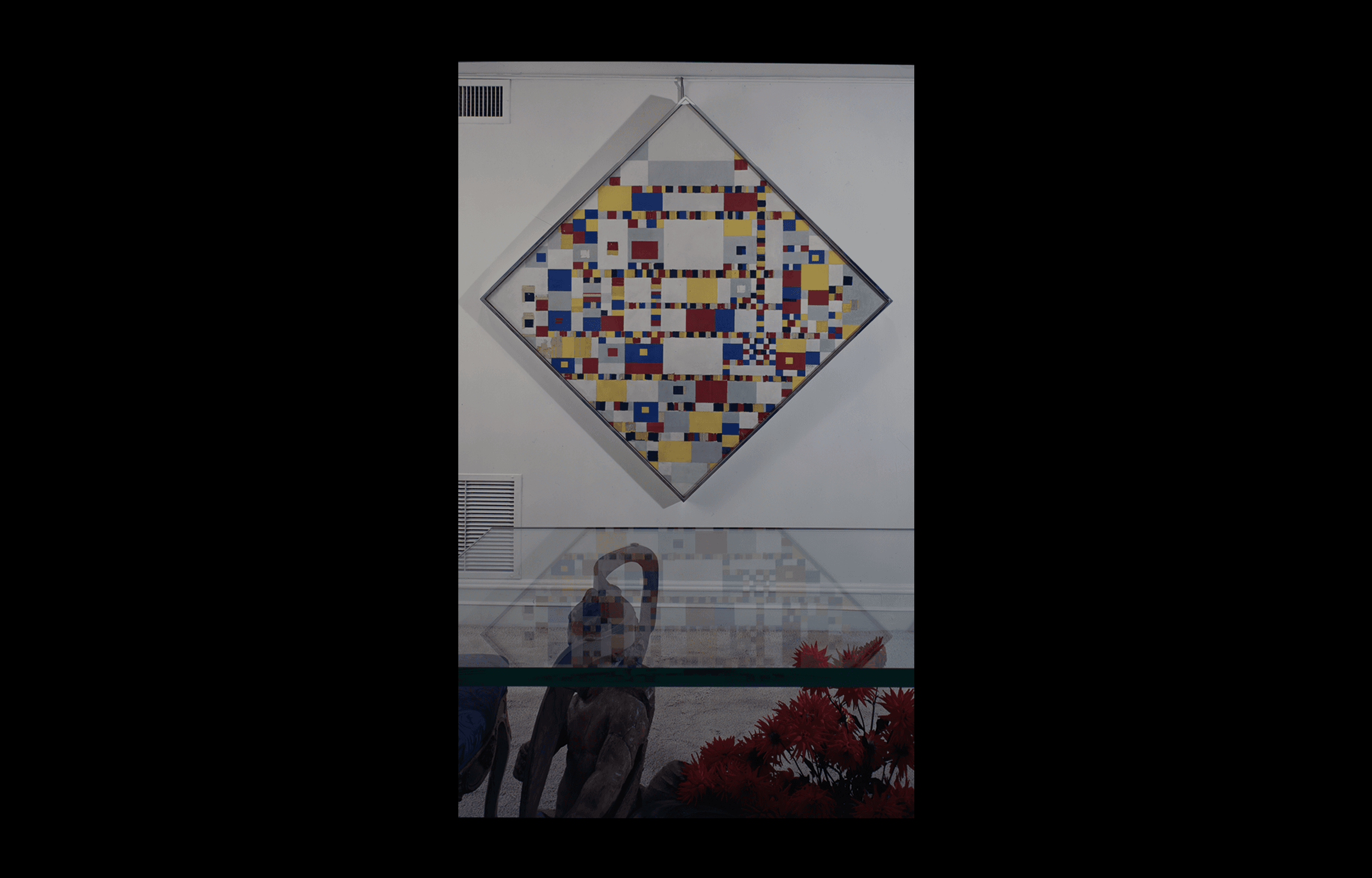

When Emily visited the gallery of Valentine Dudensing in 1944, he asked her if she would like to see Mondrian’s last painting, Victory Boogie-Woogie. According to Emily, “I will never forget the impact. I don’t think anything has ever hit me as hard as that. I called Chick [Austin] right away and I said, ‘Chick, you come down here. I’ve seen a picture where every door that Mondrian closed he has opened again. There’s a whole century of inspiration and art and ideas and vision in this thing.’”

Victory Boogie-Woogie, the last painting by Piet Mondrian, was purchased by Emily and Burton, with each paying half of the purchase price. In the same way, they also acquired Woman with a Fan by Pablo Picasso.

Image 1: New York City, 1947. Photo: Al Aumuller. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Image 2: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut Image courtesy of the Tremaine family. Image 3: Detail of Stuart Davis, For Internal Use Only, 1945–1955. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Stuart Davis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Images 4 and 5: Piet Mondrian, Victory Boogie-Woogie, 1943–1944. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“…I’ve seen a picture where every door that Mondrian closed is just opened again and I said there’s just a whole century of inspiration and art and ideas and vision in this thing…”

1945: Emily’s divorce from Spreckels became final.

Emily and Burton were married on May 5 in the home of Warren and Kit Tremaine in Scottsdale, AZ.

Emily became Art Director at The Miller Company, joining Burton who had begun to expand the product line into fluorescent lighting that was integrated into the design of new buildings. This meant getting the attention of architects, which Emily achieved in creative ways.

Acquired Departure of the Ghost by Paul Klee, painted in 1931, the year Klee left the Bauhaus, then in Dessau, Germany, where he had taught for ten years.

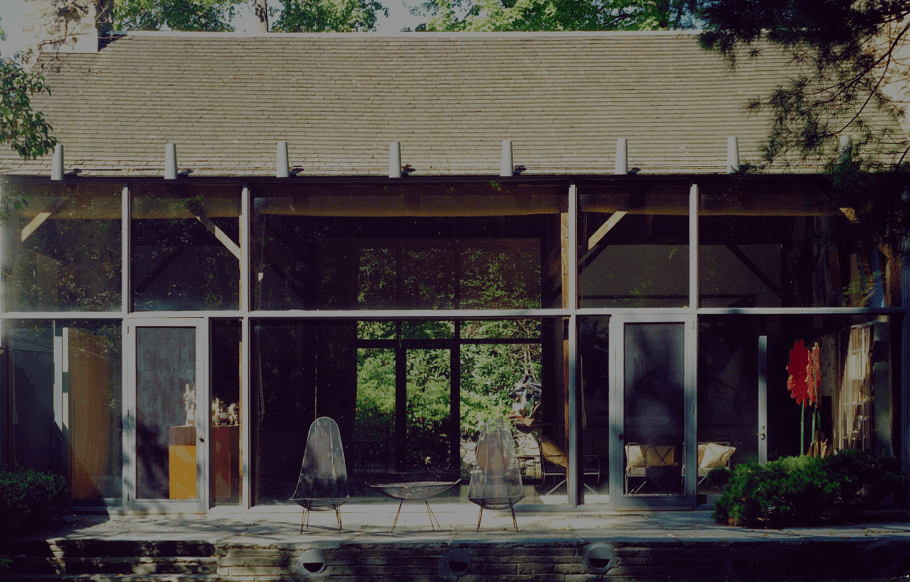

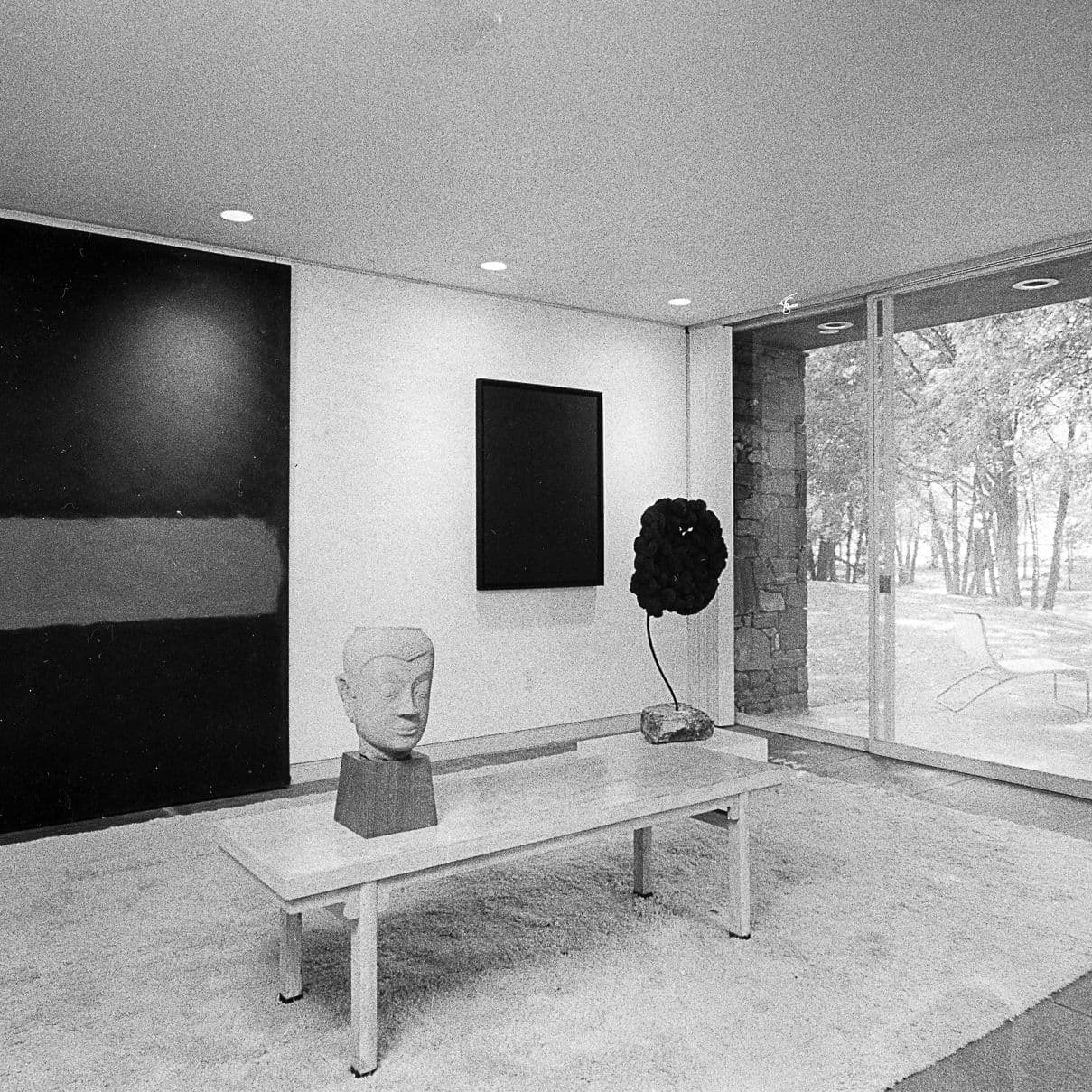

1947–48: The Tremaines hired Oscar Niemeyer to design a beach house in Montecito, and Roberto Burle Marx to design gardens, but the house was not built. Then they hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design the visitor center at Meteor Crater. It also was not built. Finally, they hired Philip Johnson for several projects including the visitor center and alterations to the Madison estate. These projects were spread over several years.

From left: Burton Tremaine Sr. (Jr.), Ernest Chilson, Partner, and George Foster, Museum Curator & Manager, at Meteor Crater, circa 1960. Image courtesy of the Tremaine family.

1947: Acquired Bougainvillea by Alexander Calder, which was constructed of sheet metal and wire.

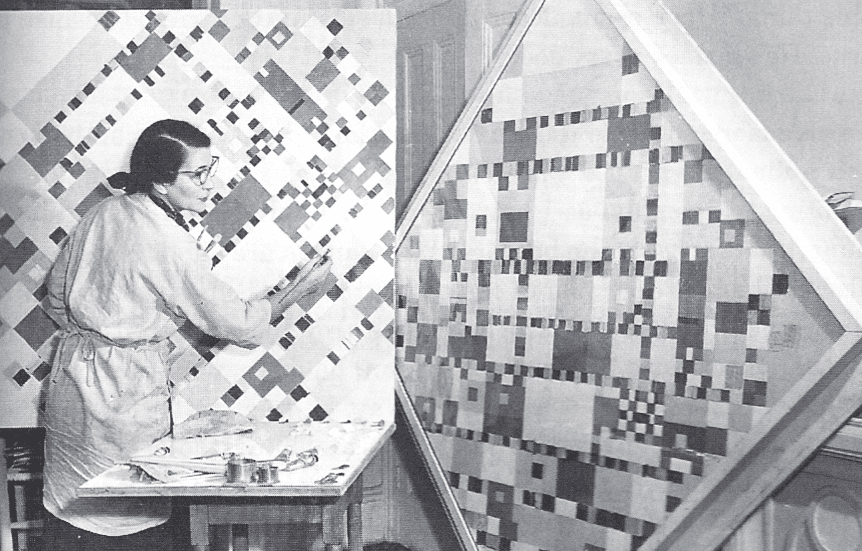

The artist Perle Fine was hired to paint an exact copy as well as an interpretation of Victory Boogie-Woogie because the original was incomplete and fragile.

Perle Fine painting an interpretation of Piet Mondrian's Victory Boogie-Woogie. Photo courtesy of Maurice Berezov ©A.E. Artworks, LLC.

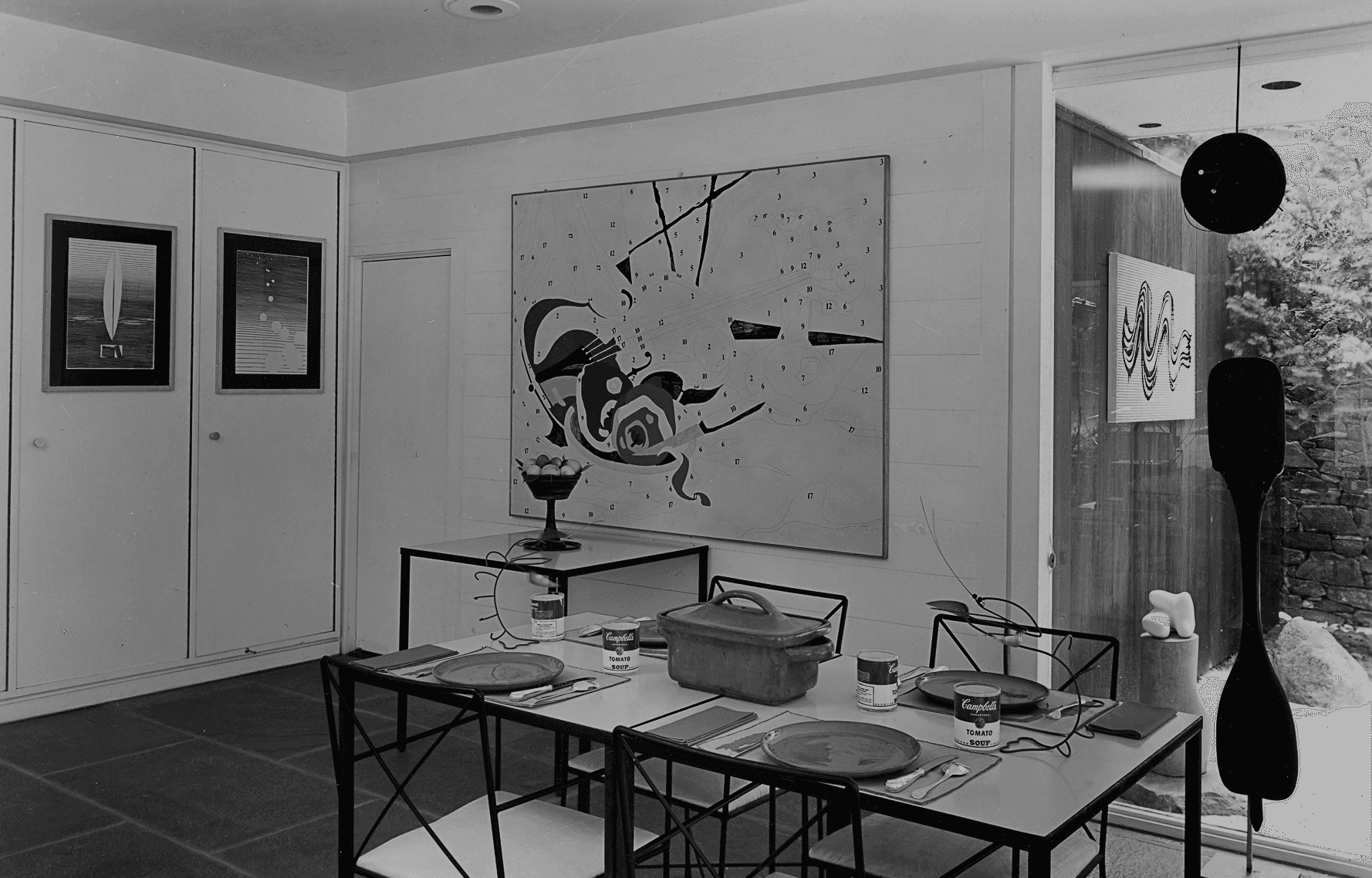

It was during this period that Emily came to see herself and Burton not as passive collectors adorning their walls solely for their own pleasure, but as catalytic patrons who could strengthen the bond between architecture and art in the United States. To help achieve this, she decided to mount a nationwide touring exhibition of the Tremaine collection under the name of Burton’s firm, the Miller Company.

In December, the exhibition Painting Toward Architecture opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Over the next two years, it traveled to galleries, colleges, and museums in at least 24 cities.

The Painting Toward Architecture exhibition would not have been particularly noteworthy had it been the Tremaines’ only major effort to become patrons of the arts and architecture during this period. However, they went one step further and decided to commission architects to design buildings that would embody the confluence of art and architecture. In one year, 1947–48, they hired five: Lutah Maria Riggs, Buckminster Fuller, Oscar Niemeyer, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Philip Johnson.

Image 1: The Miller Company logo. Image courtesy of the Tremaine Foundation. Image 2: Painting Toward Architecture, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Image 3: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“I had a very clear idea that painting had been a strong influence on architecture or I never would have suggested it. And then of course I was looking for paintings that definitely backed up the ideas, and the more I would look, the more I would see relations that I hadn’t seen before. That I'm sure other architects had seen, but until I was thinking of it myself I didn’t see it.”

1948: B.G. Tremaine died on February 16 at the age of 84 in Cleveland Heights, OH.

Acquired Euclidean Abyss by Barnett Newman. Seeing the painting at an exhibition in the Art Institute of Chicago, Burton chose it on his own, finding it so powerful he could not get it out of his mind.

1949: Acquired the sculpture Man Walking Quickly under the Rain by Alberto Giacometti.

Alberto Giacometti, Man Walking Quickly under the Rain, circa 1947-1949. From Emily Hall Tremaine’s artist file for Alberto Giacometti. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Alberto Giacometti Estate / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

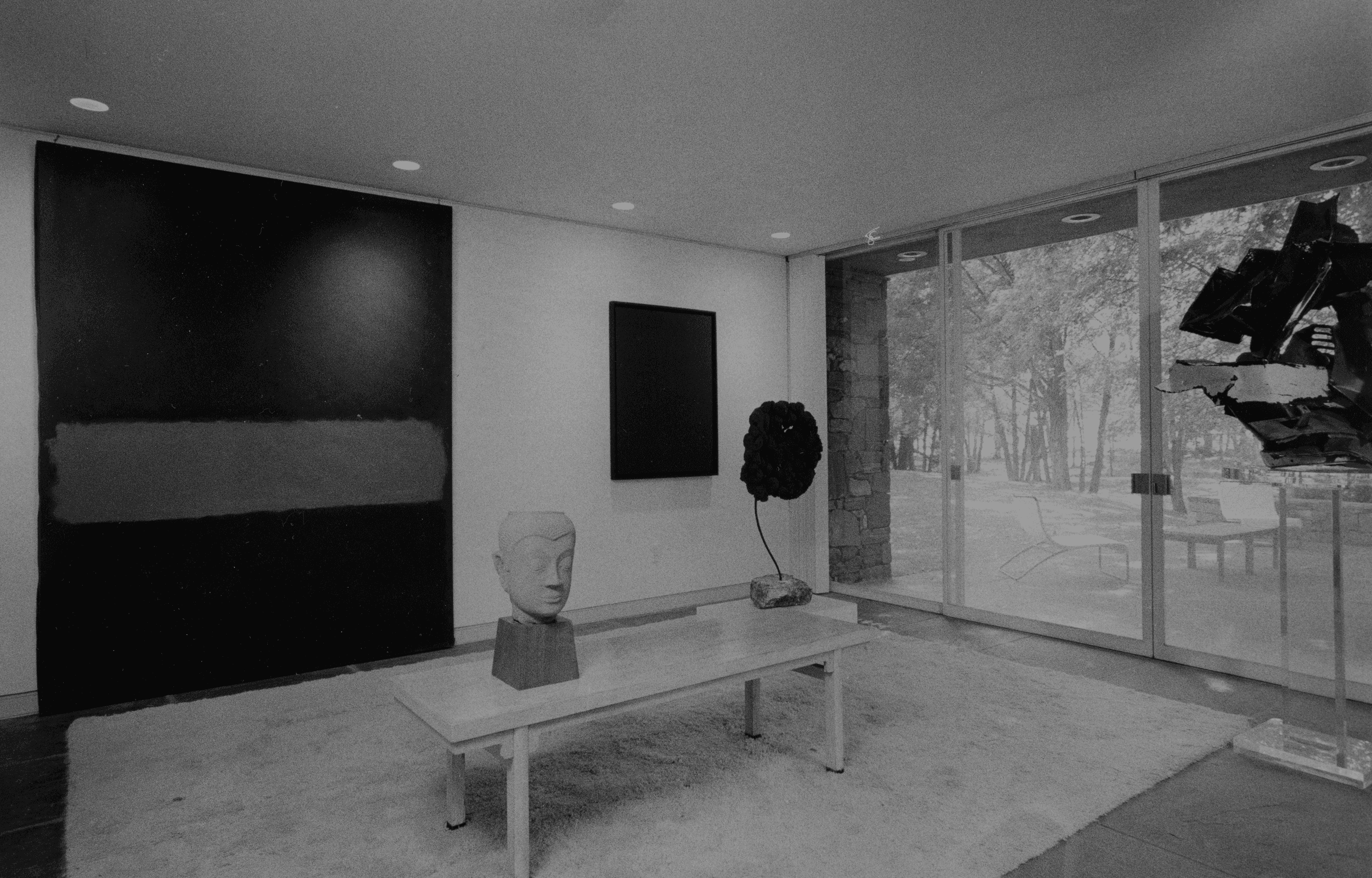

The renowned art dealer Leo Castelli once said that a real art collector is very rare. “There are many people who only buy paintings until they run out of wall space. The real collector goes on buying irrespective.” If wall space were the limiting factor in purchasing art, the Tremaines would have quit by the mid-1950s, at which point they had surpassed even the limits of their newly renovated barn in Madison, Connecticut.

“It’s a fascinating thing to understand people who live with art. If you have art in your life, it is a powerful force that can be too much for some people. But Emily had learned how to live with art, how to live with that force,” said the artist, Richard Tuttle.

The Tremaines began to shift their interest to what was happening on the edge of the art world, growing less and less conservative as the years went by. However, there were always precursors to the new works in their collection. For example, their interest in kinetic sculpture, which they started to collect in the 1950s, arose naturally from their pleasure in the Calder mobiles they had acquired in the 1940s.

Once Emily was asked how living with art had affected her thinking and attitude toward life. She replied that even though she had found qualities in artists such as Mondrian that had made her more aware of certain values, the influence was principally the other way around. “My attitude towards life, my thinking and my philosophy have influenced the collection.”

Image 1: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Video 2: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Image 3: Alexander Calder, Bougainvillea, 1945. From Emily Hall Tremaine's artist file for Alexander Calder. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Image 4: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

1953: Acquired Le Premiér Disque by Robert Delaunay and Number 8 by Mark Rothko.

The International Arts Council was formed by MoMA. The Tremaines became active members.

Robert Delaunay, Le Premiér Disque, 1912–1913. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

1956: Acquired Frieze by Jackson Pollock, which he finished not long before his fatal automobile accident.

1958: Acquired Tango and White Flag by Jasper Johns; Moon Garden Reflections and Moon Garden Series by Louise Nevelson; and Lehigh by Franz Kline, among others.

Emily served as treasurer of the International Arts Council.

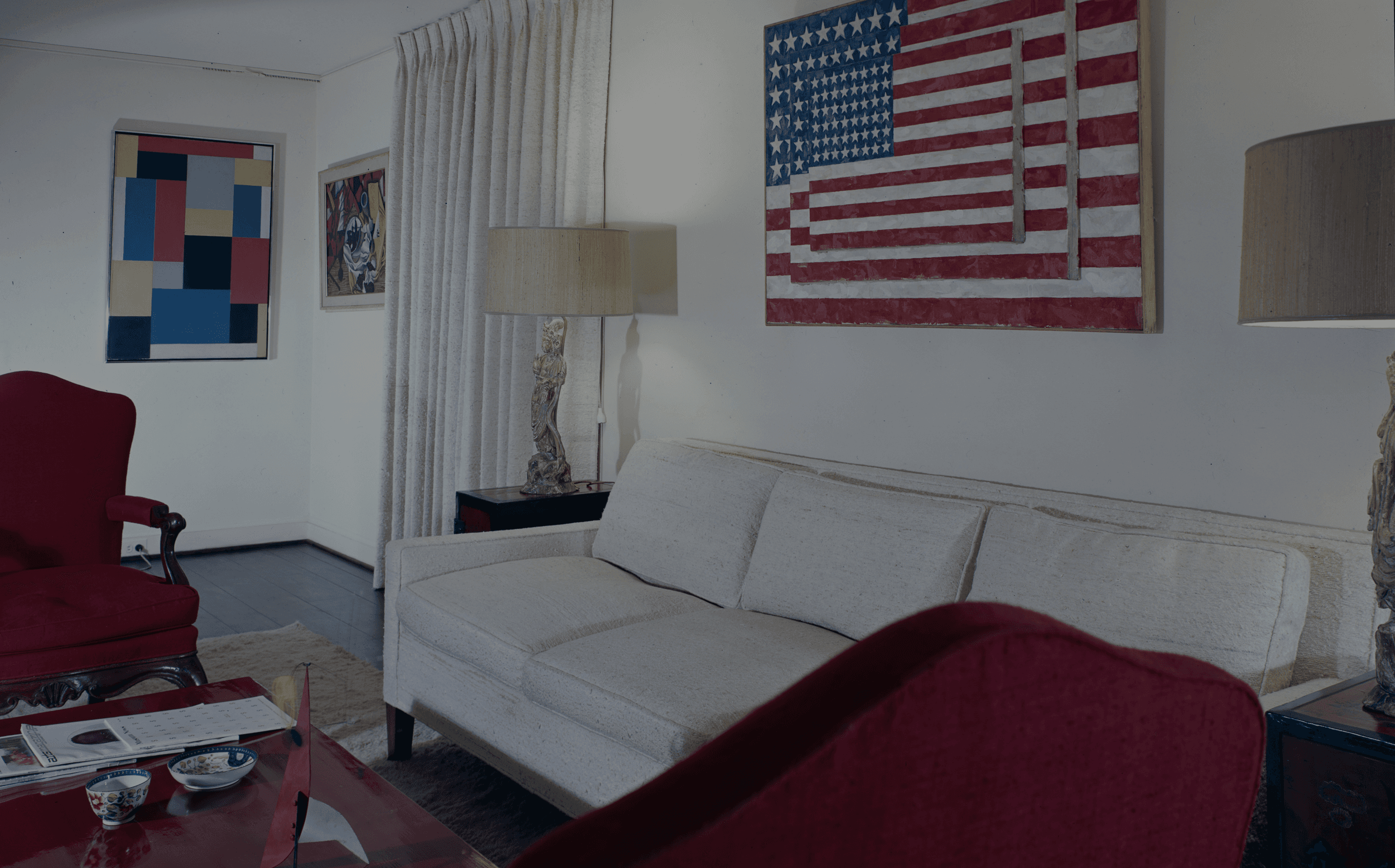

1959: Acquired Three Flags by Jasper Johns, which Emily considered to be “a great new invention.”

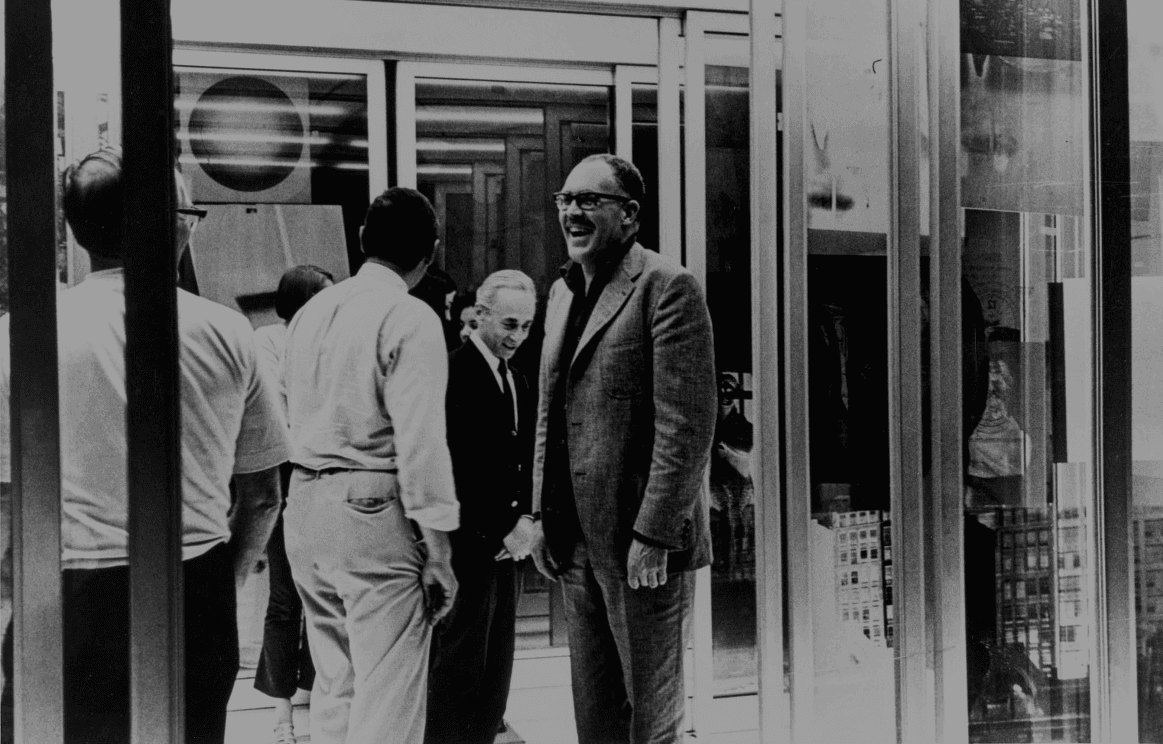

According to Johns, Leo Castelli told the Tremaines “that Tango was the only thing available after my show, which was true. I remember they didn’t believe him and subsequently came to my studio.” On that trip, they saw the unfinished Three Flags and instantly wanted it. Recalled Emily, “I sensed immediately upon seeing Three Flags that it was a great new invention.”

In the final analysis, art collecting was the glue in their marriage. “It brought them both joy, the fun of the hunt, getting up in the morning and having something to do together, to be all embroiled in what was going on in the art world and the intrigue with dealers,” concluded John Tremaine, their grandson. “That is what drove them. It kept them both young.”

Image 1: Leo Castelli with Jasper Johns. Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Image 2: Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine. Image courtesy of the Tremaine family.

1960: Acquired Villa Borghese by Willem de Kooning.

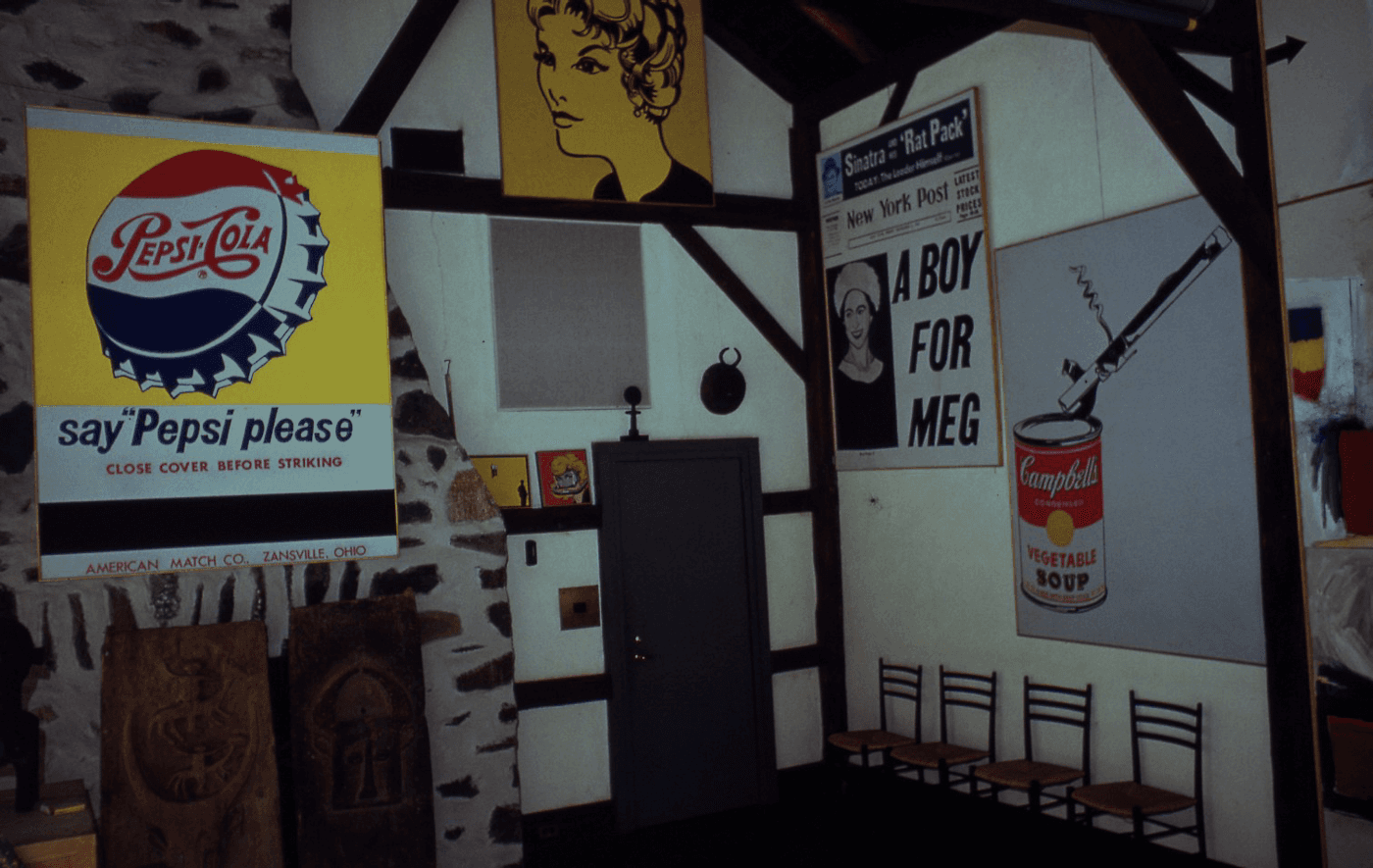

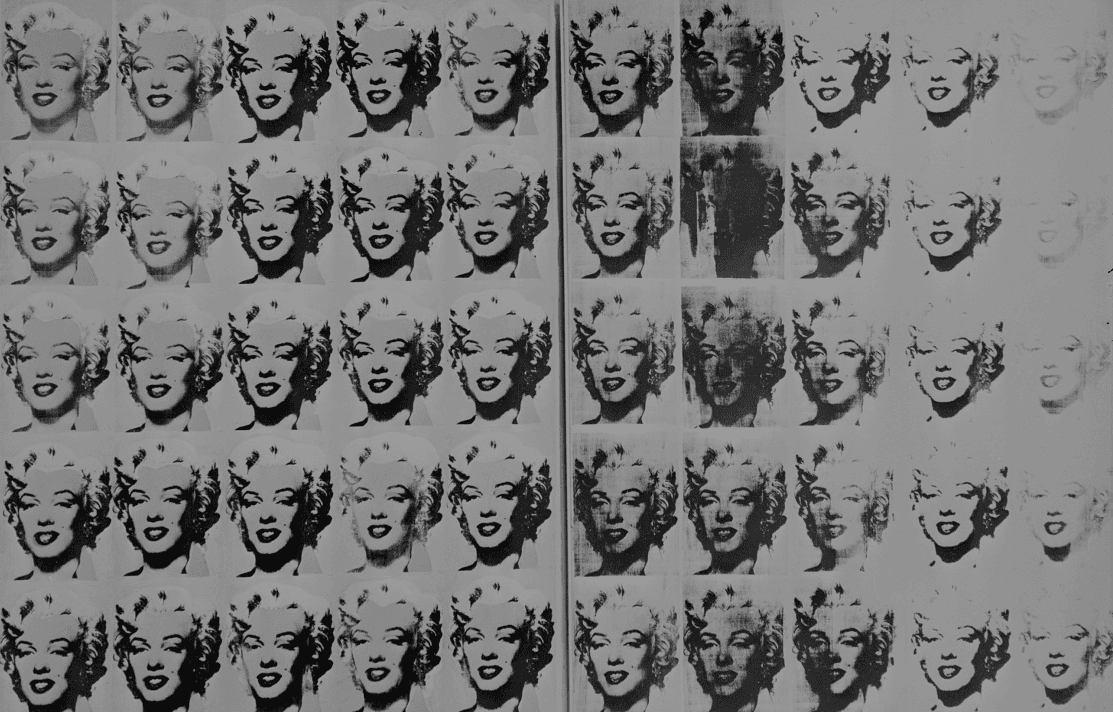

1961: The Tremaines began to purchase pop art, including many works by Warhol, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, and Lichtenstein.

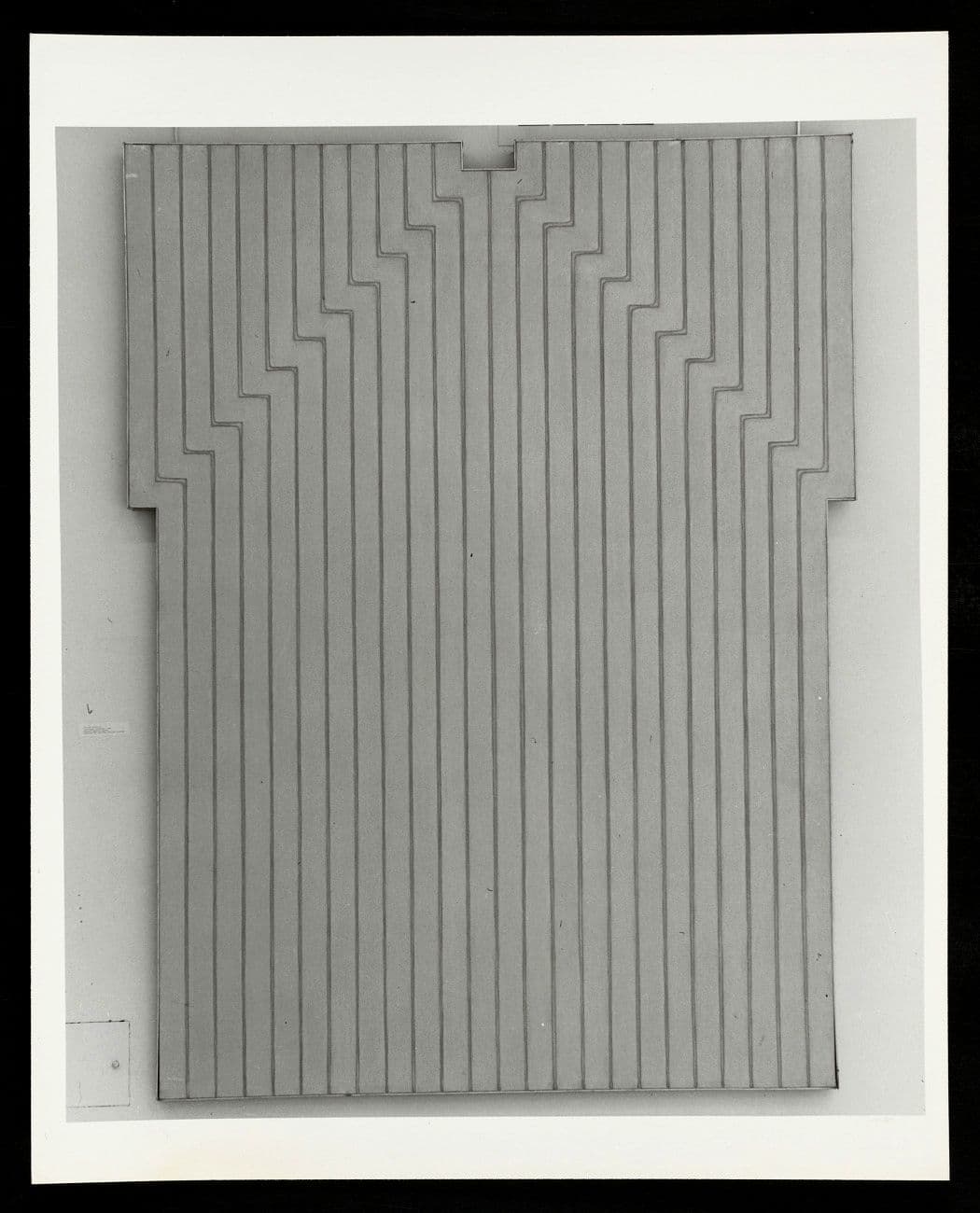

Acquired Luis Miguel Domínguin by Frank Stella.

Frank Stella, Luis Miguel Domínguin, 1960. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1962, the Tremaines purchased fifteen works from Andy Warhol before he even had a regular dealer. By so doing, they helped fuel his meteoric rise. Pop was not really new. It hadmany artistic antecedents. What was new was the speed at which it crossed the line to respectability. This was not brought about by dealers or museums. It was brought about by private collectors. And the Tremaines would be the leaders of the pack.

Emily said, “We made several visits to Andy’s studio and came to think of both Andy and his work as perhaps the most enigmatic and complex of any of the artists we were beginning to know.” Warhol was so thankful [for their support] that one Christmas morning he left leaning against their door a small gold Marilyn Monroe as a present.

From Emily’s personal standpoint, the most powerful reason that Pop had died so soon was that it had turned from playful to sardonic; it had moved from aesthetic comment to social criticism. When James Elliot, director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, consulted with Emily about the wisdom of buying one of Warhol’s electric-chair paintings for the museum, she was adamantly opposed; the painting was altogether too dismal.

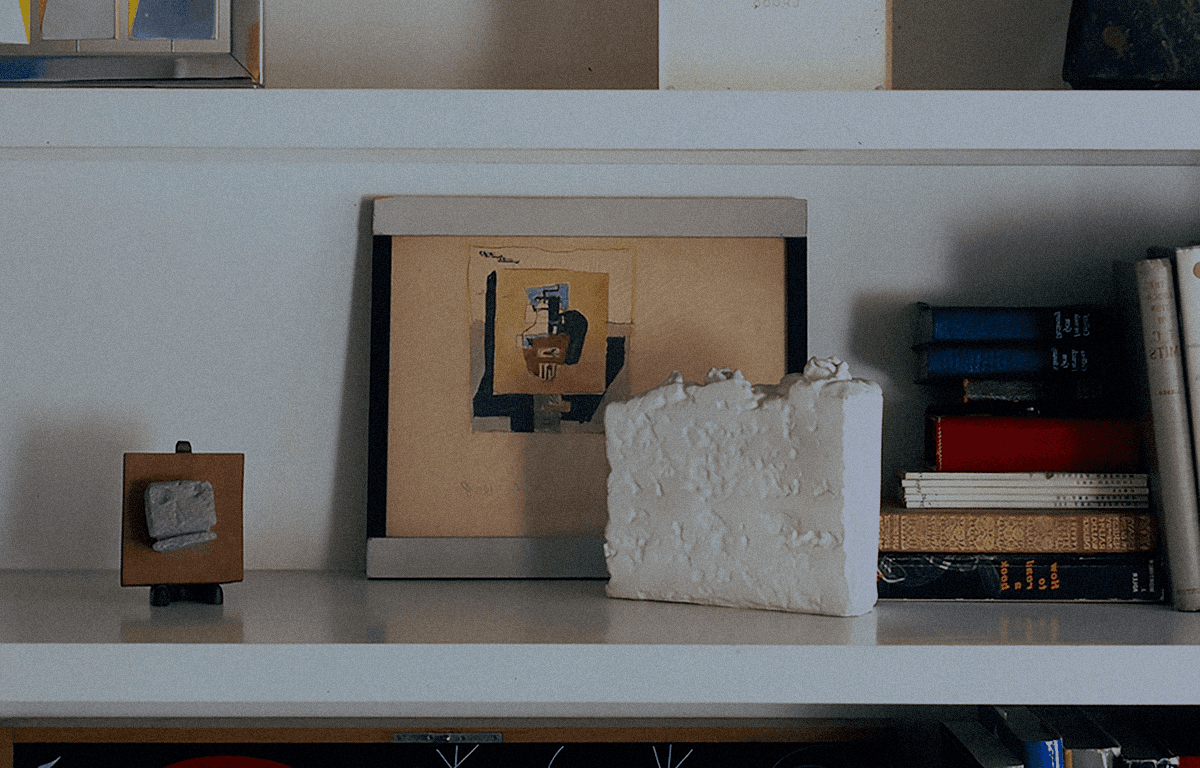

Although Emily moved the art around a great deal, as old works were loaned and new works acquired, her goal always was to achieve resonance across time, space, and style. Asked once what it was like to live in the midst of such visual intensity, Emily said simply that it was like living with books. “I never sit in front of art that I don’t get ideas, It’s a catalyst.”

Image 1: The Tremaine’s barn with works by Andy Warhol. Image courtesy of the Tremaine family. Image 2: Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, 1962. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image 3: Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, 1960s. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image 4: The Tremaines’ Madison home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

1966: The Tremaines set up the International Art Foundation to be administered by the National Gallery of Art to which the Tremaines donated 90 works over an eight-year period. However, the plan to loan art to museums around the country did not work out due in part to changes in the tax law. The foundation eventually came to an end.

1968: Emily suffered a recurrence of tuberculosis.

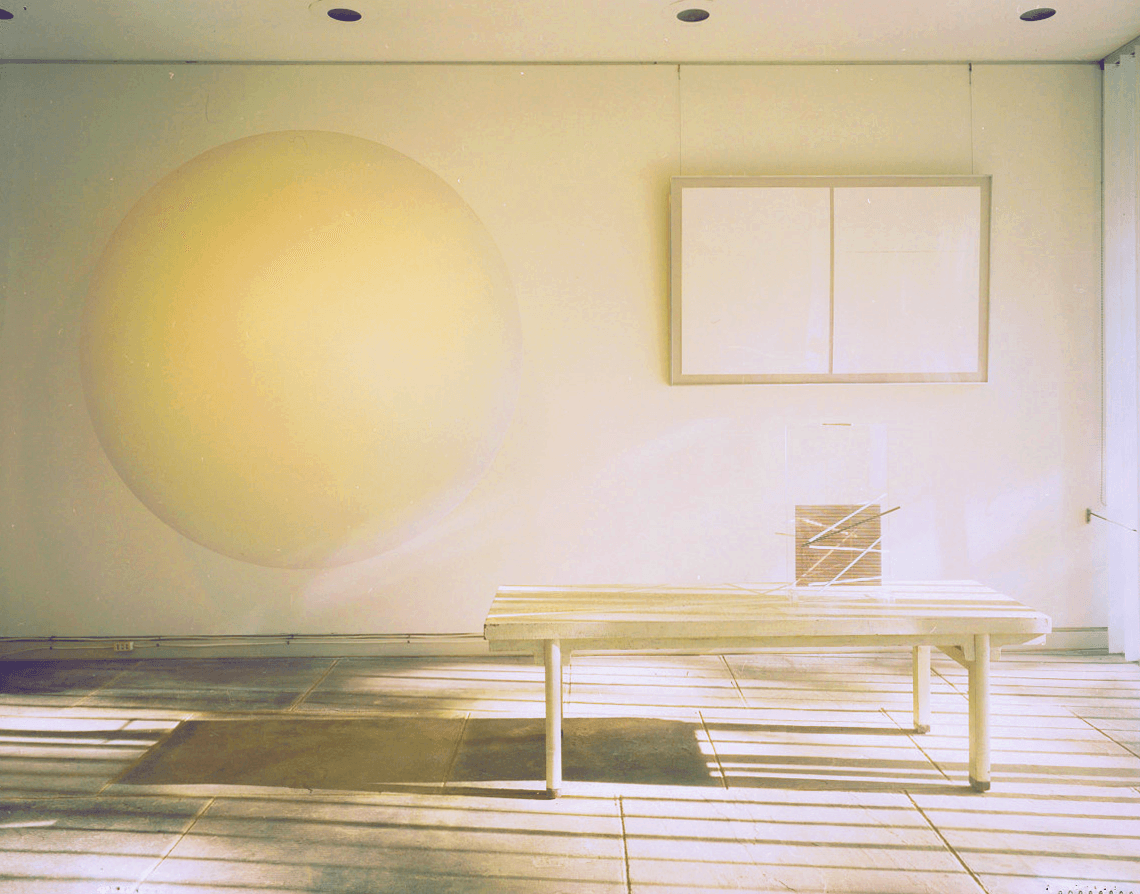

1970: Acquired Untitled by Robert Irwin and redesigned a room in Madison to exhibit it to its best advantage.

The Tremaines' Madison home with Untitled by Robert Irwin, a drawing by Walter De Maria, and a sculpture by Jesus Rafael Soto, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

1974: Increasingly interested in Earth works, the Tremaines allowed Walter de Maria to use land at their Bar T Bar Ranch as a testing site for The Lightning Field.

Agnes Gund, who eventually became president of the Museum of Modern Art, benefited from Emily’s guidance when she first became interested in art. She felt indebted to Emily for taking her to artists’ studios, teaching her to look at art herself, and encouraging her to get to know the artists personally. Once she told Emily how much she admired their painting by Rothko and remarked she wished she could acquire a Rothko. Without hesitation, Emily said, “Let’s go to Rothko’s studio.” Gund concluded, “She really did care and know the artists. I think I would have never had the richness of my life without her example.”

According to the artist, Neil Jenney, “Emily wasn’t afraid to spend her money on a nobody. She didn’t need the judgement of other collectors to know the value of an artist’s work. I was a relative nobody when she came to my place the first time. She came with a friend [Agnes Gund] one day to my small gallery space. I left them alone to look at the paintings, hoping they’d write out a check. When I came out and saw what she had chosen, I remember thinking, My God, Emily always chooses the best painting.”

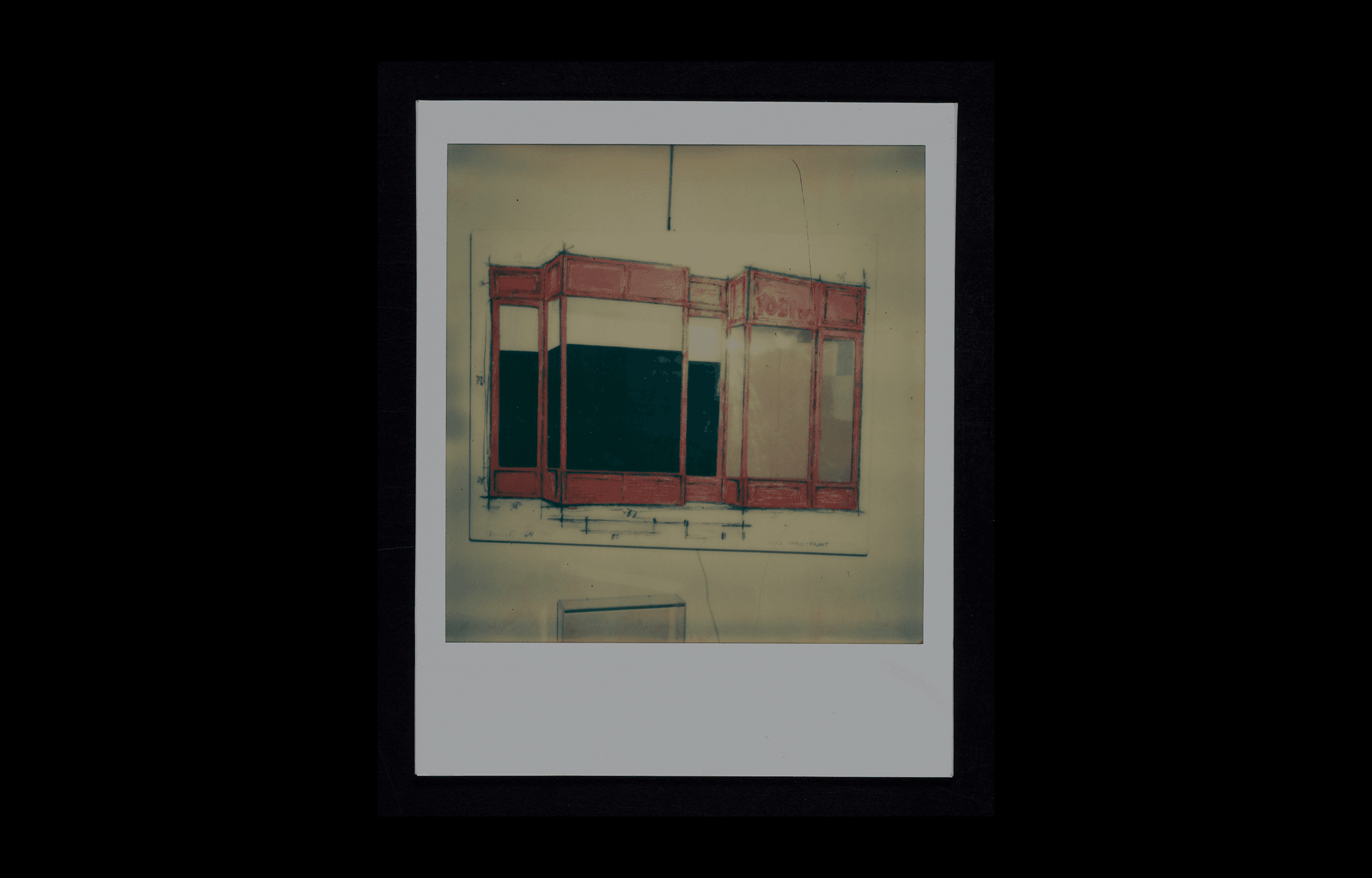

Among the young artists the Tremaines found fascinating was Christo. Their purchase of Double Store Front at a time when few people were buying his work was of great importance to him. He explained, “Double Store Front was about urban architectural spaces, and it preceded my work with covering things. Mrs. Tremaine was not a fashionable collector. She was a fine collector. She was a passionate collector, and passionately collecting art is an extremely private business.”

As the value of their paintings continued to escalate, Emily admitted to a sense of satisfaction that went beyond aesthetics: “I recall Esquire magazine once suggested that a collector has one of three motives for collecting. A genuine love of art; the investment possibilities; or its social promises. I have never known a collector who was not stimulated by all three. For the full joy and reward, the dominant motivation must be the love of art; but I would question the integrity of any collector who denied an interest in the valuation the marketplace puts on his pictures.”

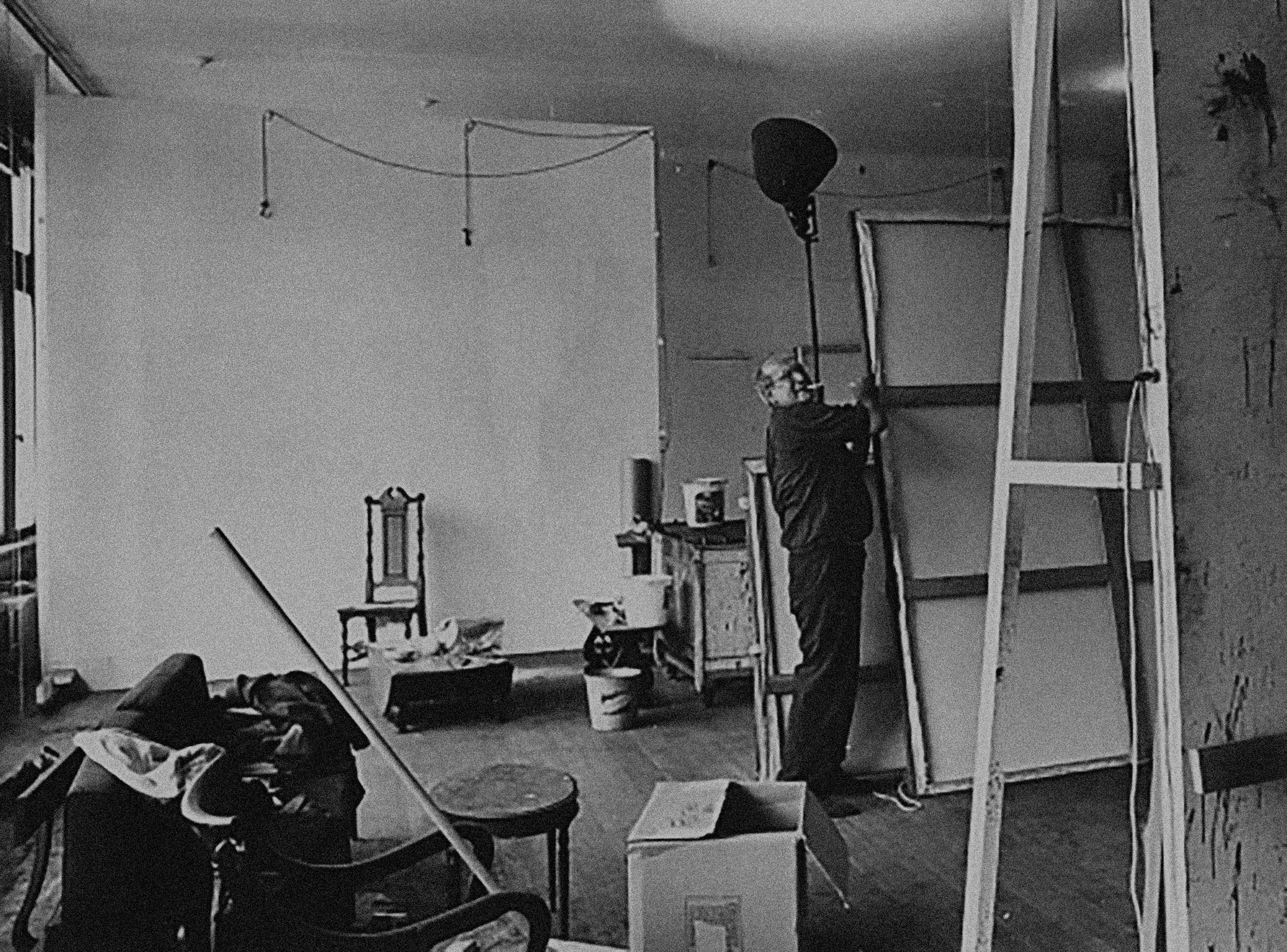

Image 1: Mark Rothko in his studio. © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography. 2: From Emily Hall Tremaine's artist file for Neil Jenney. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Image 3: Polaroid, Christo, Double Store Front, 1964. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Video 4: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

1980: Dissatisfied with museums, the Tremaines began to sell art, including Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe Diptych to the Tate Gallery in London. The biggest sale was Three Flags to the Whitney Museum of American Art for $1,000,000, at that time the highest price ever paid for the work of a living artist.

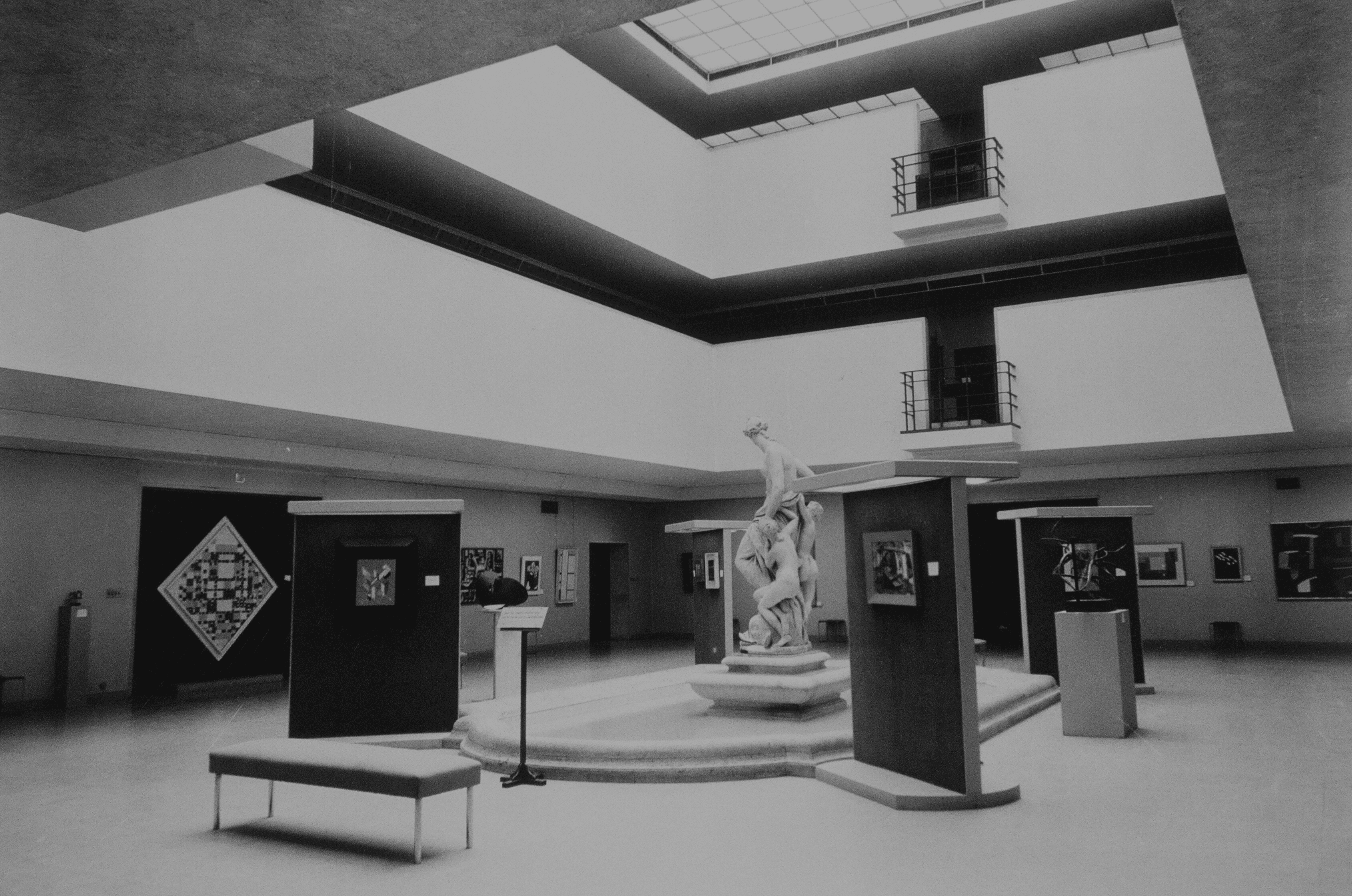

1984: On February 25, a major exhibition opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum titled The Tremaine Collection: Twentieth Century Masters, the Spirit of Modernism. Over the years, the Tremaines donated at least 140 works to the Wadsworth and after Emily’s death endowed the position of Emily Hall Tremaine Curator of Contemporary Art.

Acquired Venus by Jean-Michel Basquiat, the last major painting to enter the collection.

Emily said in an interview that she had no plans to keep the collection intact after her death because she couldn’t bear the idea of the work being shut up in some museum storage area. To her it was a living thing; better a life on the walls of a private collector than death in storage. According to Tracy Atkinson, director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, Emily “looked on the paintings as her children.”

Mark Rothko’s No. 8 (1952), Paul Klee’s Departure of the Ghost (1931), Roy Lichtenstein’s Ceramic Head with Blue Shadow (1966), and Alexander Calder’s Bougainvillea (1945) in the Tremaine’s home. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

1987: Emily died on December 17 in Madison at age of 79. Prior to her death, she had established a philanthropic foundation. During their married life, Emily and Burton equally split the purchase and sale price of art. The foundation was to be endowed by the sale of Emily’s half of the collection, which at its peak contained approximately 400 works of art, making it one of the most significant collections in the United States.

1988: Victory Boogie-Woogie was sold for $11 million to S. I. Newhouse through the art dealer Larry Gagosian.

Having made the decision neither to donate the collection to museums nor to sell it privately, the Tremaine family chose Christie’s to handle an auction, which was held on November 9 in New York City. The timing was good and the auction was very successful.

A touchstone is a stone that indicates the purity of gold that is brought into contact with it. Victory Boogie-Woogie was the touchstone of the Tremaine collection. Against it, every other work of art was assayed. If it was pure, it stayed; if it was impure, it was donated or sold. After Emily’s death in 1988, negotiations continued with Larry Gagosian on behalf of S. I. Newhouse to buy the painting. Burton Jr. said, “Then along came an offer from Newhouse on the Victory Boogie-Woogie for $11,000,000.”

Piet Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie in the Tremaine home. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

1991: Burton died on March 23 at age 89 in Palm Springs, CA.

The second auction at Christie’s was held on three evenings, November 5, 12, and 13. By then, the art market had begun to cool, so the second auction was not as successful as the first. However, because of the guarantee provision in the contract with Christie’s, the Tremaines did very well. The two auctions surpassed $60 million, which was in addition to the prior sales of art that topped $24 million.

Following the two successful auctions at Christie’s of the Tremaine collection in 1988 and 1991, Tracy Atkinson, director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, wrote what amounted to a benediction for the paintings: “They formed a wonderful ensemble which will not be seen again, but that is in the nature of things and indeed it has been very much in the nature of this collection which has waxed and waned in both size and scope over the years as new developments came along in the art world, and as the Tremaines ‘traded up’ towards that extraordinary standard of quality which they set for themselves from the very first.”

The Tremaine home with Three Flags by Jasper Johns on the far right. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

With this substantial endowment, The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation came into existence. Burton’s son, Burton Tremaine Jr., served as the first chairman, and family members served on the board. The Foundation chose to emphasize education with a focus on art, environment, and learning differences. According to its Mission Statement, the Foundation’s efforts “reflect the entrepreneurial spirit of our family forebears and the founder’s distinction for foresight, imagination and risk taking.”

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.