Story

Optical Illusions and Disillusions:

Emily Hall Tremaine and Bridget Riley

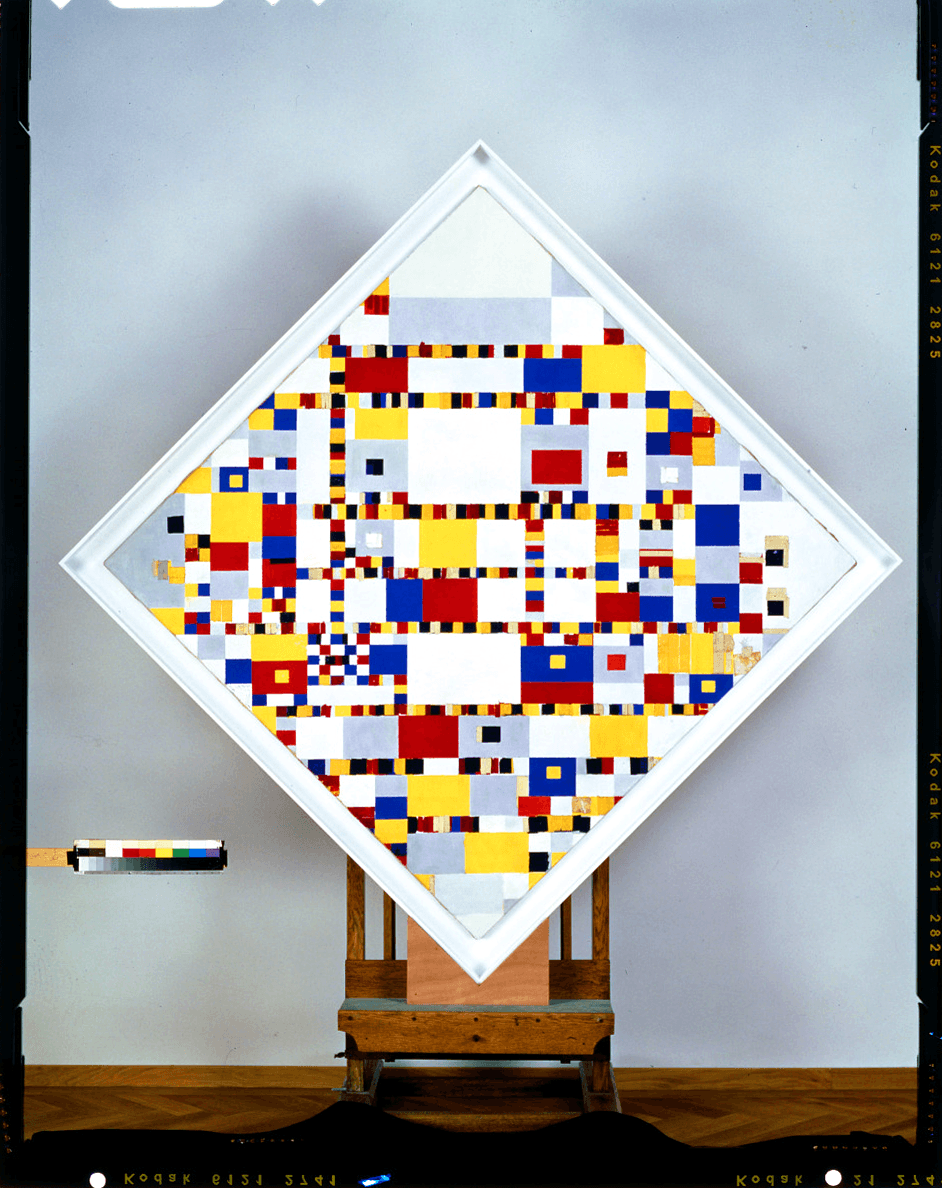

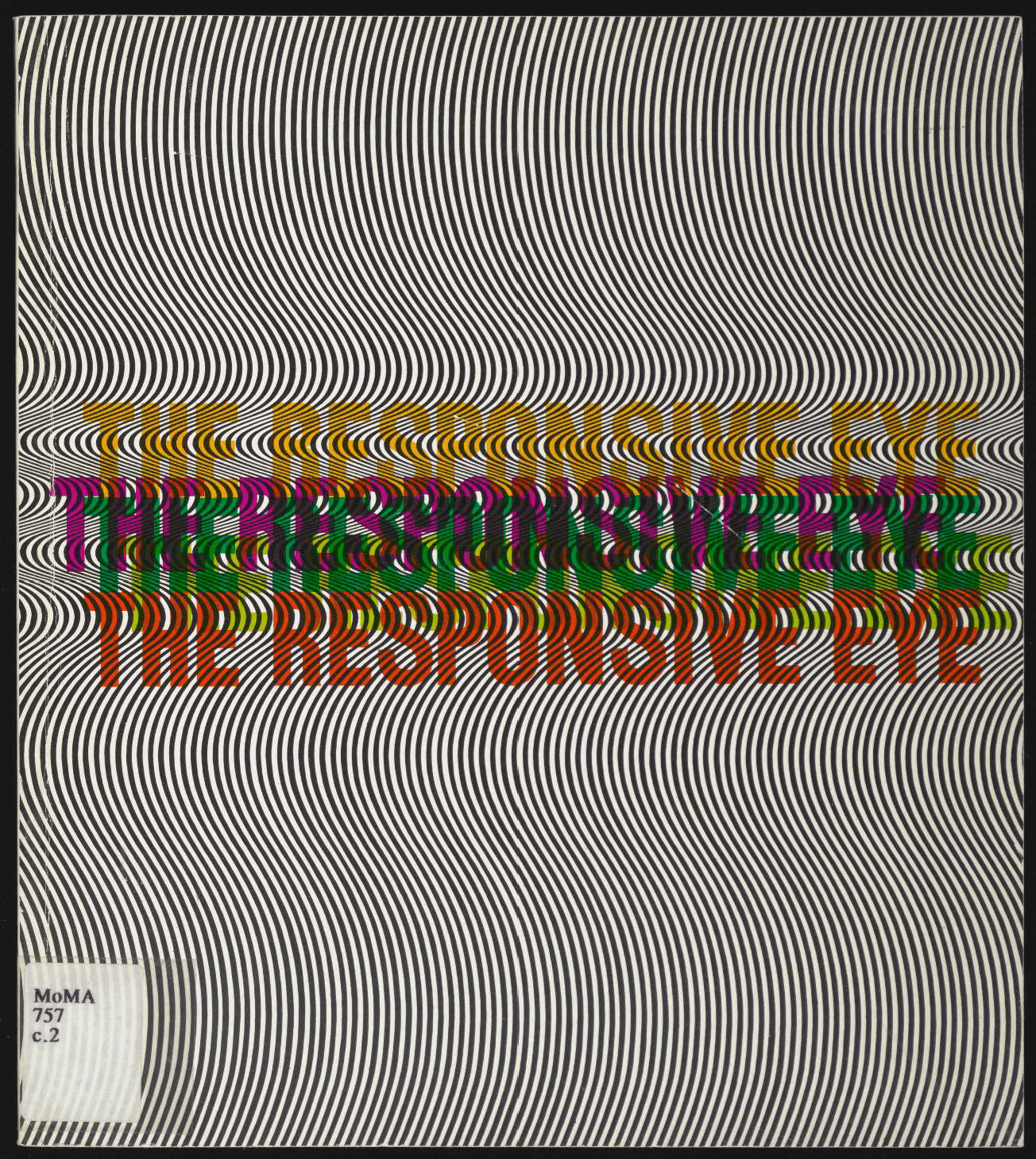

When the British artist Bridget Riley visited New York City in the late winter of 1965, she was discouraged by the critical reaction to her op art paintings. Two were included in the visually stunning exhibition The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art. But while the exhibition, featuring 99 artists, was a popular success with over 180,000 visitors streaming through the galleries, it was not a critical success. Far from it. One critic even claimed the art wasn’t even art but just an optical trick.

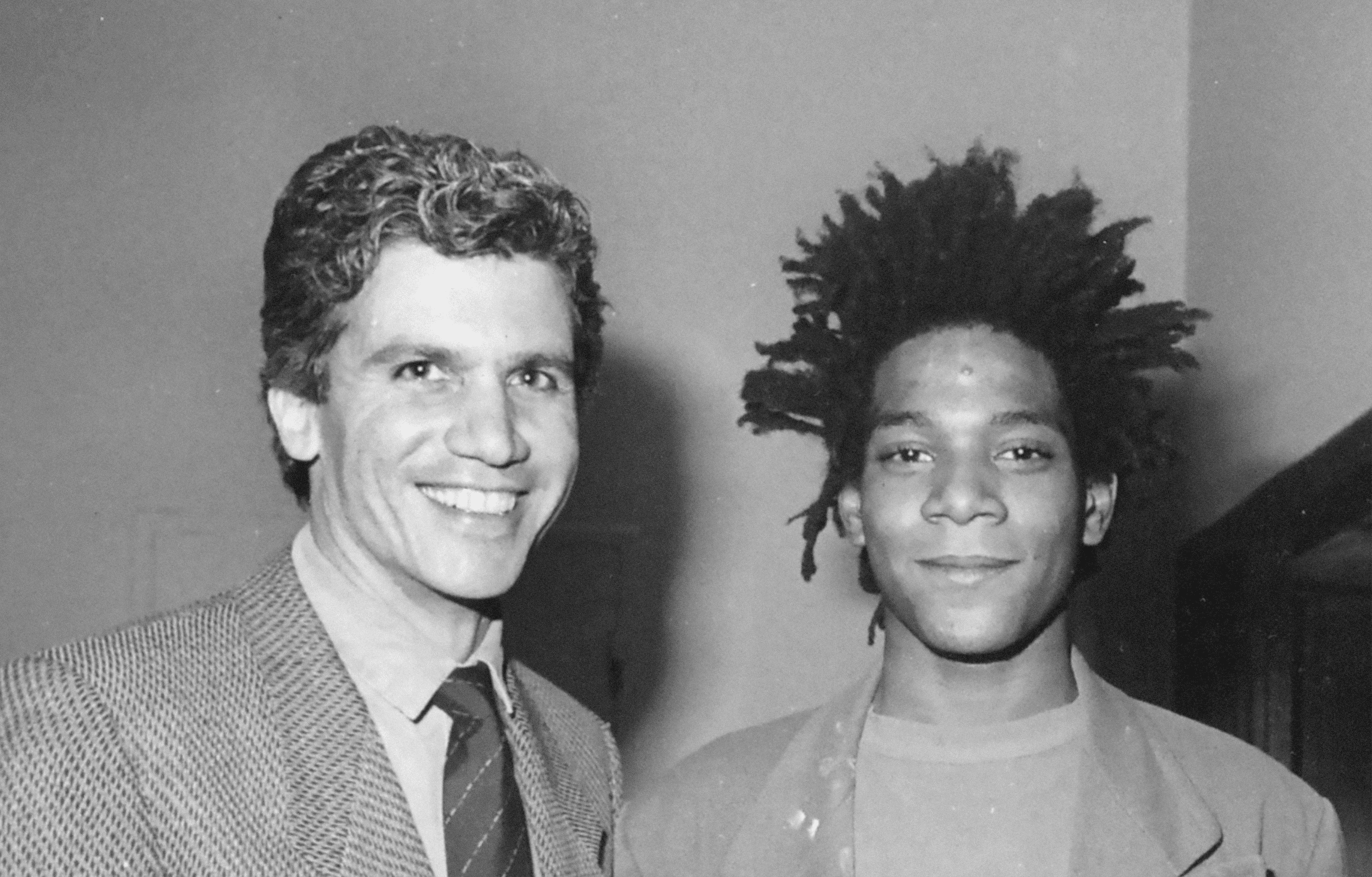

The Responsive Eye (curated by William Seitz) at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1965, with Bridget Riley’s Hesitate at the end of the corridor. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

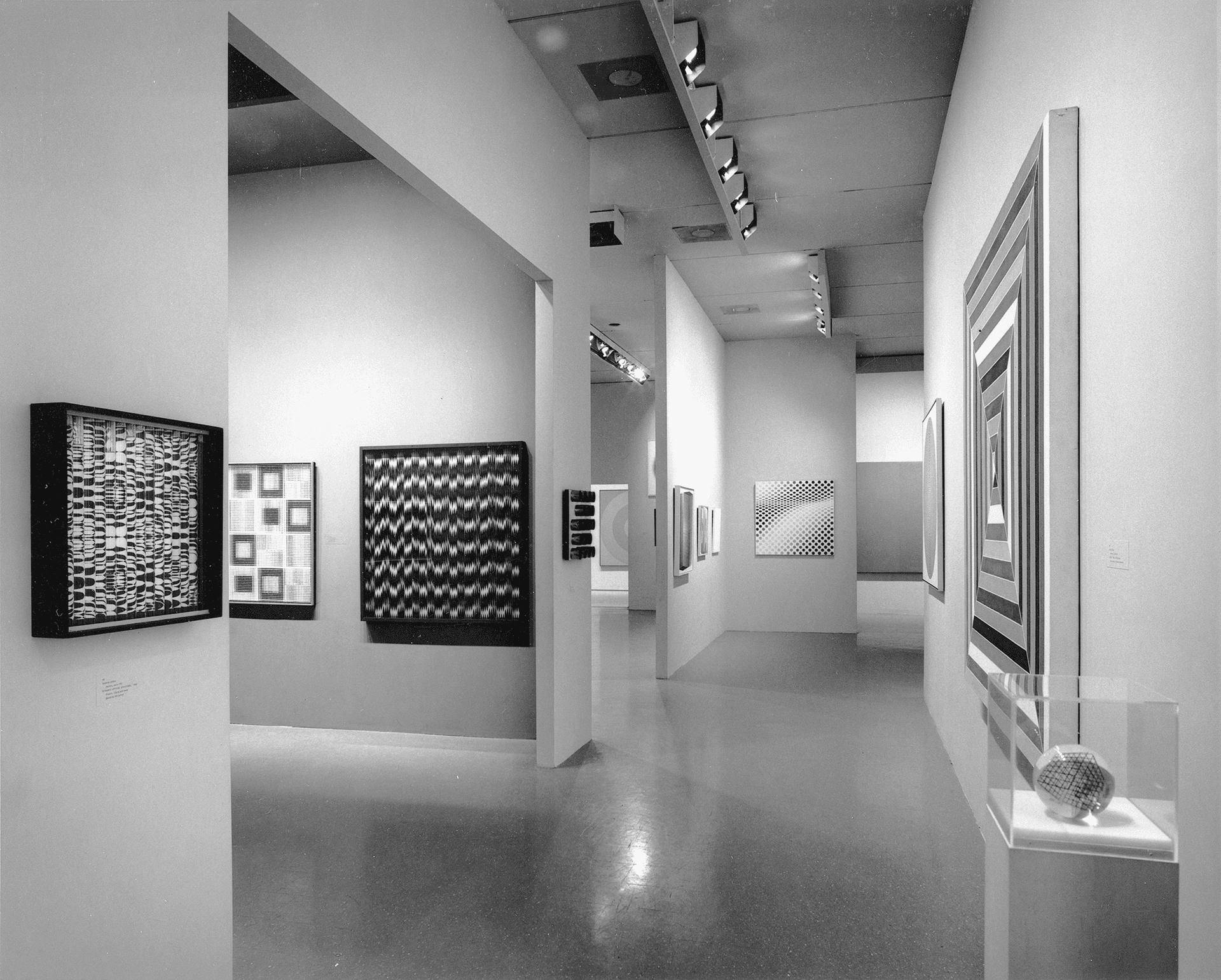

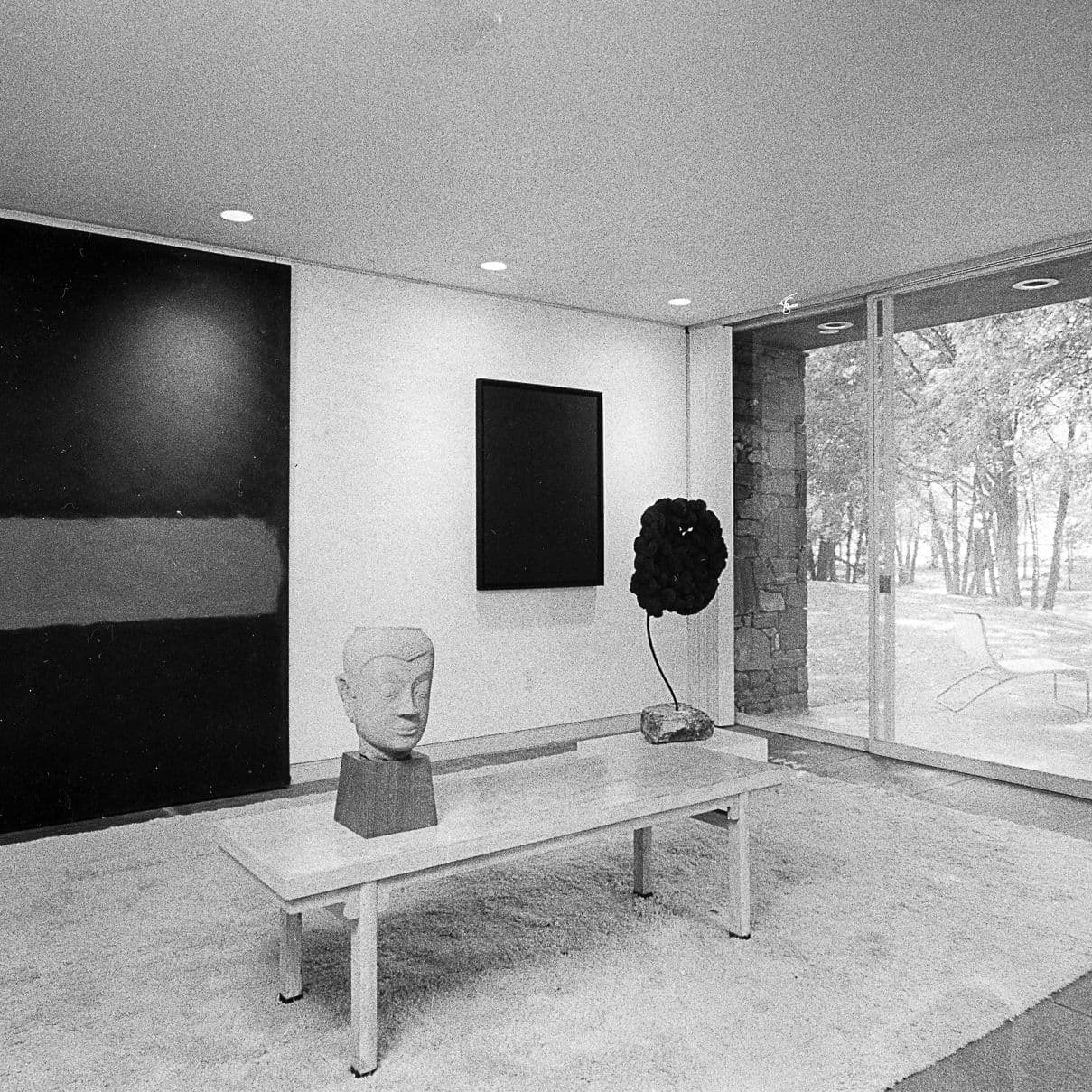

Emily Hall Tremaine disagreed. Aware that Riley was downhearted, Tremaine invited her to come see her stellar modern art collection. Over and above all the Picassos, Pollocks, and Rothkos displayed in the museum-quality setting of her Park Avenue apartment, Tremaine wanted to show Riley one painting—Piet Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie—the sublime canvas that summed up everything Tremaine believed about art.

“Bridget Riley wrote me from London and said she didn’t want to come to New York unless she was sure she could see the Victory…”

The Tremaine home with Victory Boogie-Woogie (right of fireplace) on the wall. Photo: Adam Bartos. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“We [Emily Hall Tremaine and Bridget Riley] went into another room and there, to my amazement and delight, was Victory Boogie Woogie displayed on an easel. We looked at it together. A few of the tapes were coming away from the surface and hanging down. She asked me what I thought she should do about these and as the painting was unfinished whether this mattered? I said that I thought that the reason that the painting was unfinished was because Mondrian had fallen ill—he had simply not had the time and wasn’t well enough to complete it. So, it didn’t matter. But the painting—as it was—showed that a great change was taking place in his way of working and we were able to ‘see behind the scenes’—a rare privilege in late Mondrian.”

Bridget Riley, 2023

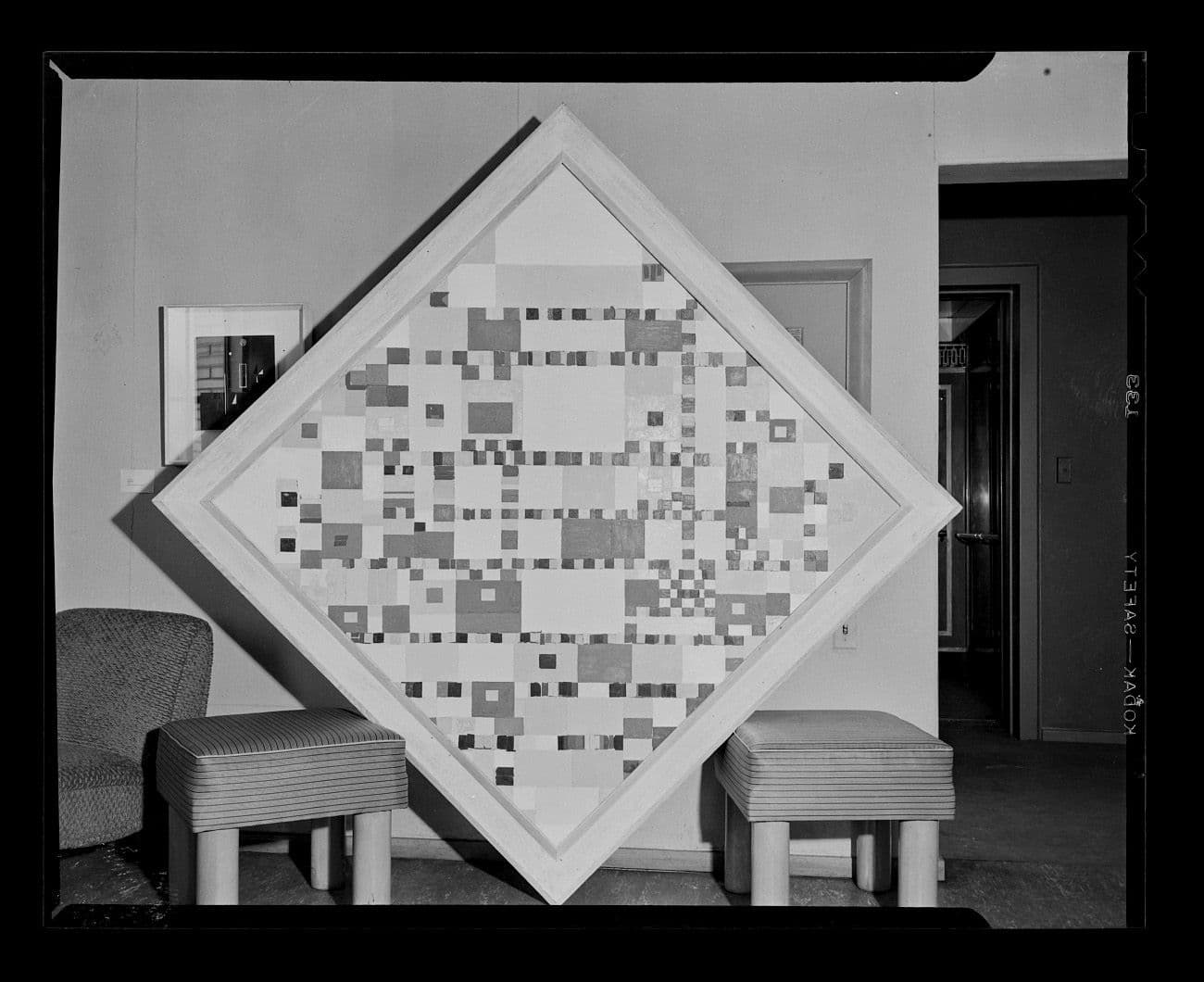

The Tremaines’ personal photography of Victory Boogie-Woogie. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Tremaine hoped that Riley would comprehend the advances Mondrian had achieved in geometric abstraction, specifically how in Victory Boogie-Woogie he had used the grid to point beyond itself with, as Tremaine put it, “no beginning and no end.” New directions in art, such as op, were not really new. There were always precursors that the next generation of artists tried to either destroy or uphold. Or better yet—exceed.

Having seen Victory Boogie-Woogie when it had been loaned by the Tremaines to a European museum, Riley told her that “it was the greatest influence” on her work. Riley was not the only artist that Tremaine invited to see Victory Boogie-Woogie, but she was probably the one most in need of encouragement. Tremaine liked to quote one of Mondrian’s most famous aphorisms, “If we cannot free ourselves, we can free our vision.”

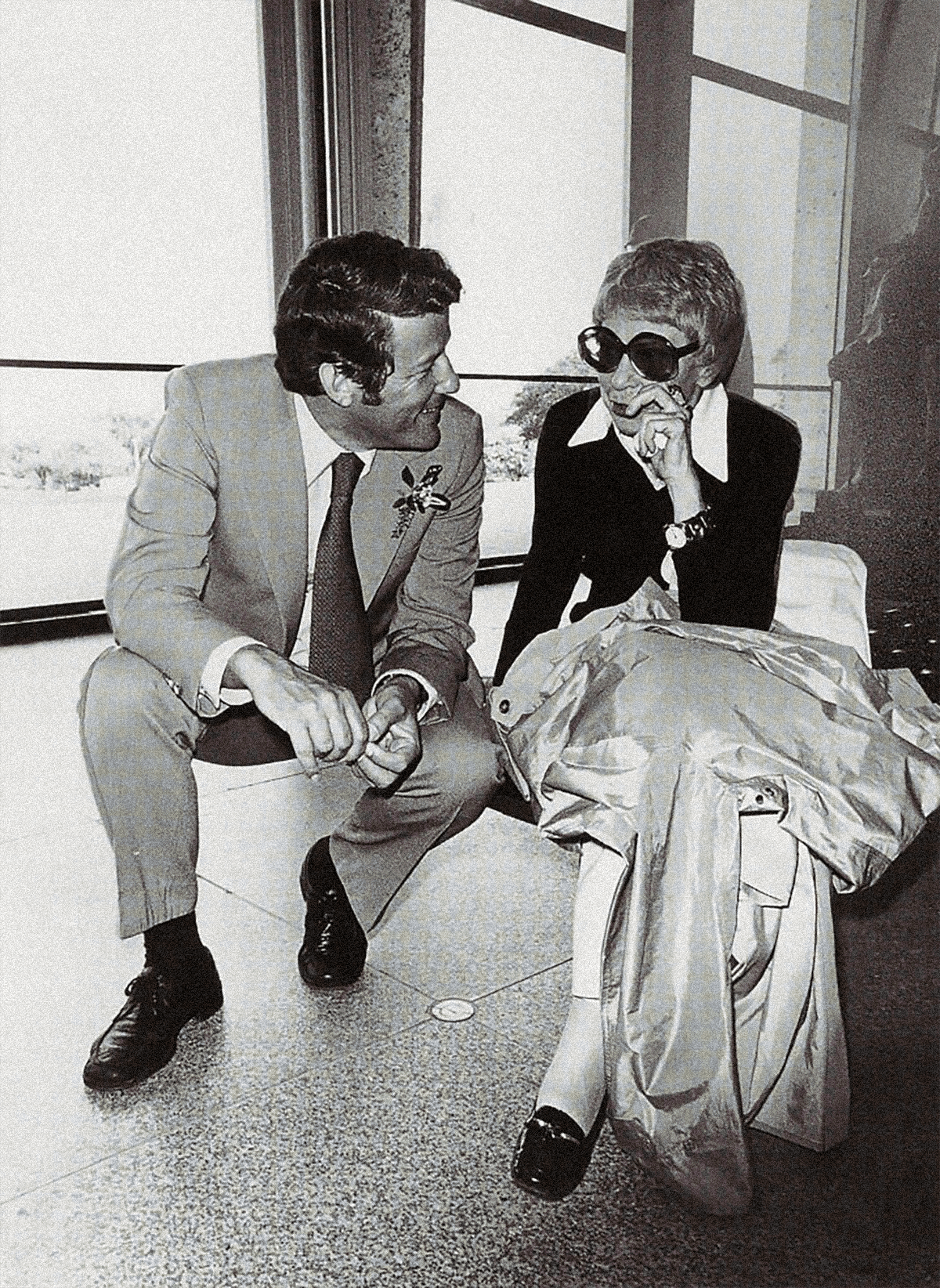

Emily Hall Tremaine and Steingrim Laursen of Copenhagen, Denmark, at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, spring meeting of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, 1976. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890–2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

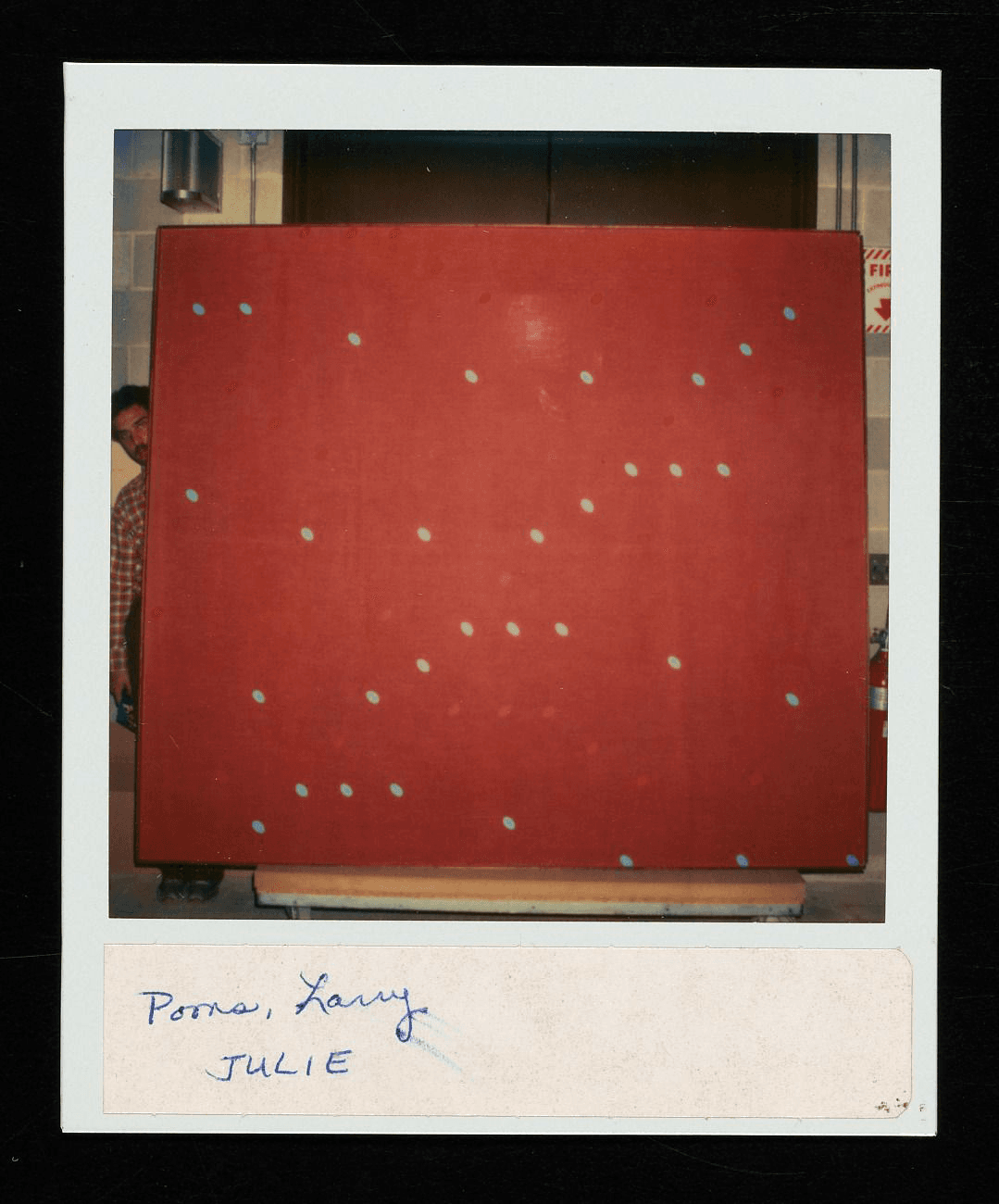

Tremaine’s attraction to Riley’s art was peaked by The Responsive Eye. As a member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, she was aware in advance of the art that William Seitz, the curator, had selected, including Riley’s Hesitate and Current. In fact, he had chosen Current for the cover of the exhibition catalog. However, Riley was not the only artist in the show to whom Tremaine paid attention. She and her husband, Burton, owned (or would come to own) paintings by sixteen of them, including Robert Irwin, Agnes Martin, Larry Poons, and Frank Stella.

There was agreement that the show highlighted a fresh direction, but that was the only thing on which there was agreement. Even its name was contentious. In fact, the MoMA press release listed several possible synonyms such as optical, retinal, cool, hard-edge, color imagery, even a peculiar category titled “visual research.” Some art critics were not pleased. Thomas Hess complained in a review for Artnews that the show was a “mishmash” that lumped together very different styles.

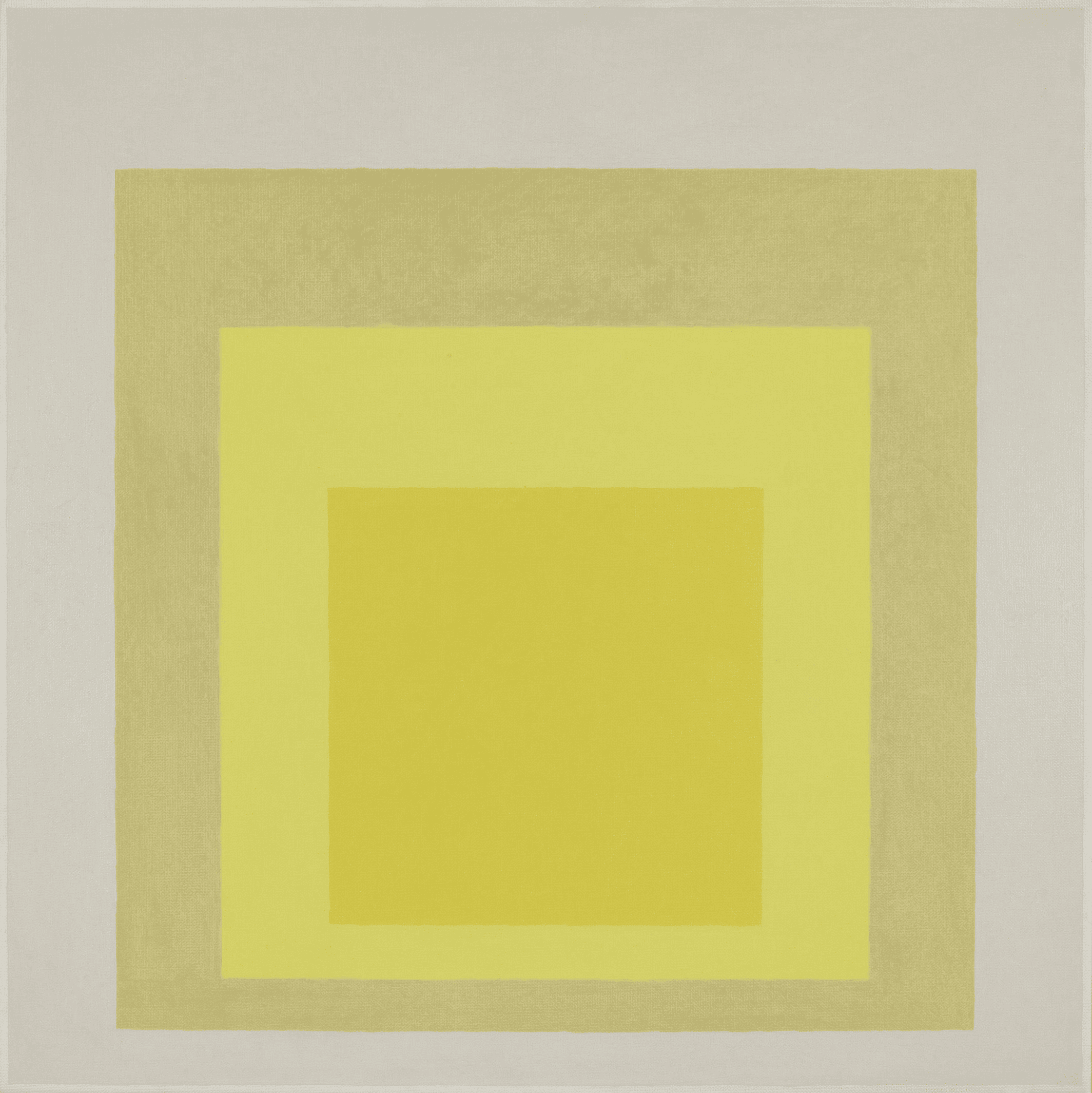

Neither were all the artists in the show pleased, among them Josef Albers whose paintings Flying and Homage to the Square: Arrival were already in the Tremaine collection. Having taught at the Bauhaus in Germany before immigrating to America where he taught at the Black Mountain School and then at Yale, he disdained the word op, although Richard Anuszkiewicz, one of his former students, embraced it. Anuszkiewicz’s work was also in the exhibition.

“My work has developed on the basis of empirical analyses and syntheses, and I have always believed that perception is the medium through which states of being are directly experienced.”

Bridget Riley

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square, 1963. Oil on board, 48" × 48". Image courtesy of the Tremaine Foundation. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

To the artists who were seriously committed to the style, the name hardly mattered. Op art explored the nature of perception in the scientific age. It created visual sensations that were real states of being—energy states that existed separately from the painting itself. Riley wrote, “My work has developed on the basis of empirical analyses and syntheses, and I have always believed that perception is the medium through which states of being are directly experienced.”

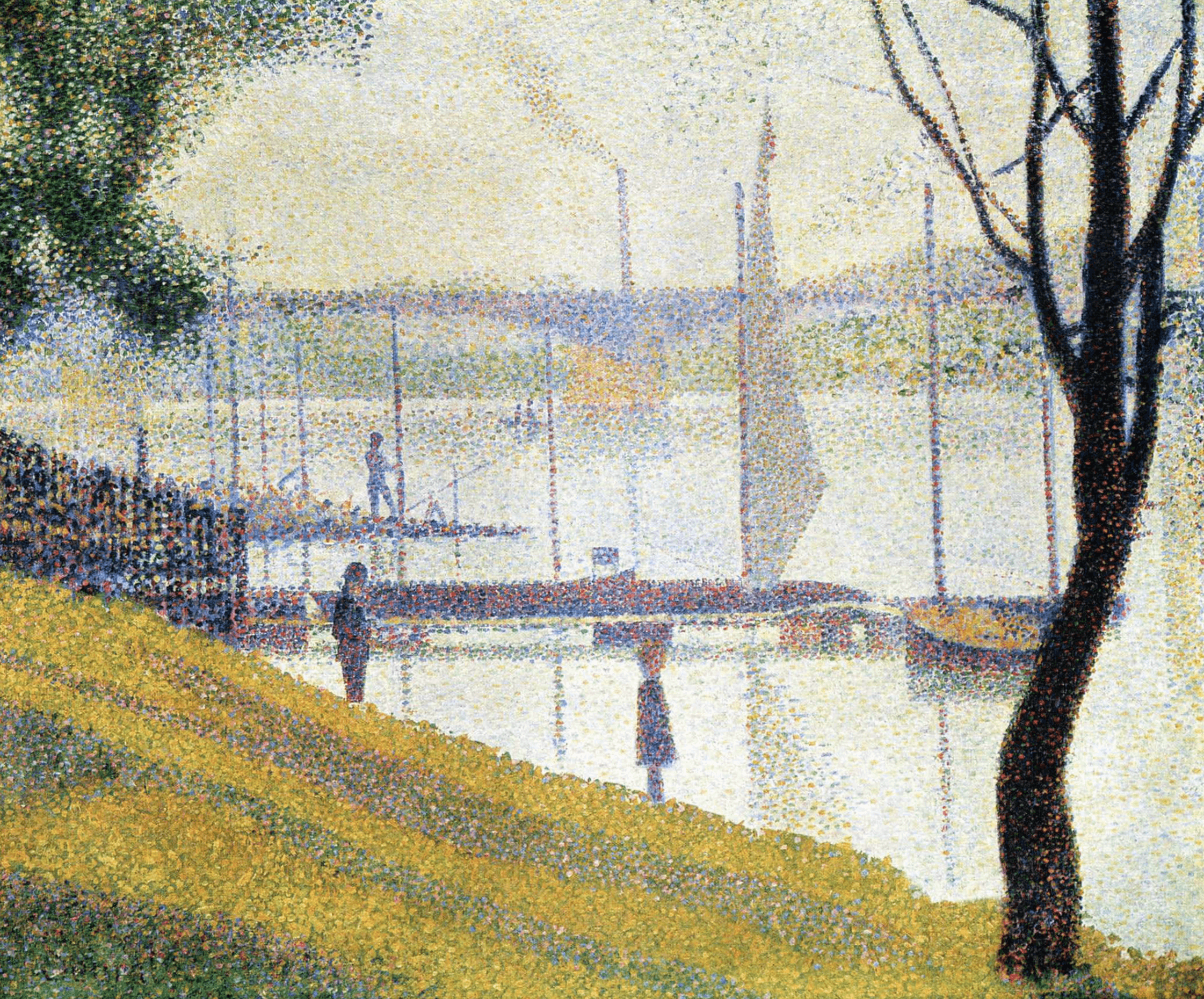

Georges Seurat's The Bridge at Courbevoie.

Seitz wrote in the catalog that the intent of The Responsive Eye was “to dramatize the power of static forms and colors to stimulate dynamic psychological responses.” He referred to the connection between optical art and the pointillist technique of the French impressionist Georges Seurat, a connection that Riley herself made explicit. Earlier in her career she had copied Seurat’s The Bridge at Courbevoie to learn how he used color in a scientific way.

By the time of The Responsive Eye, Riley had moved away from color and begun using black, white and gray, charting their placement precisely. To Seitz, the stimulating effects of movement and illumination resulted in pulsations of startling intensity. “The eyes seem to be bombarded with pure energy, as they are by Bridget Riley’s Current.” Seitz’s choice of the title The Responsive Eye was apt because it shifted the focus from what was happening on the canvas to the physiological reaction of the eye and the psychological reaction of the brain.

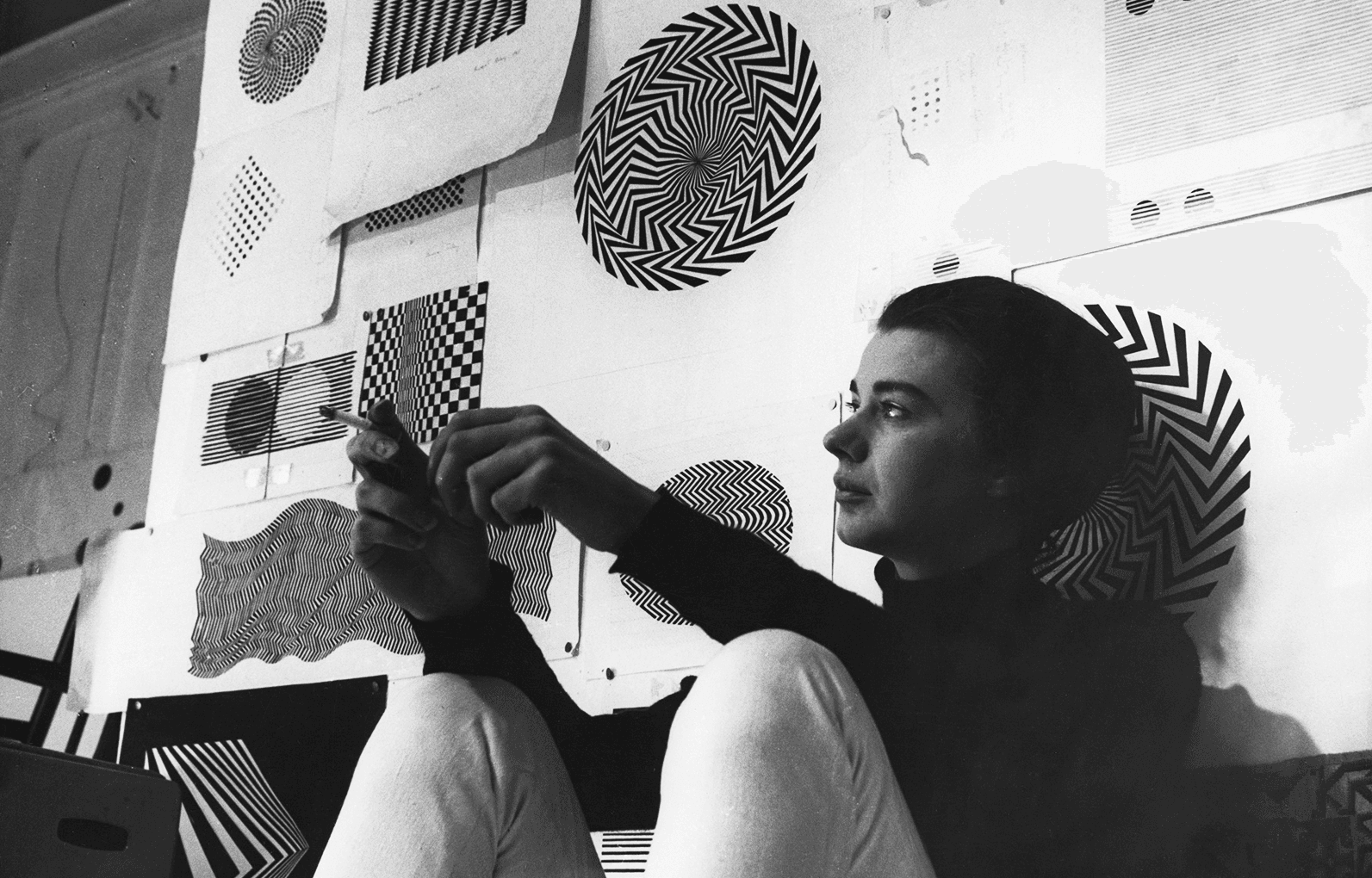

Bridget Riley in her Warwick studio, London, 1964.

Background: Portrait of the British artist Riley, Bridget (b.1931) Credit: Private Collection ©The Lewinski Archive at Chatsworth. All Rights Reserved 2024/Bridgeman Images. Foreground: © Arts Council / Courtesy of the BFI National Archive (Abstract Artists in Their Own Words)

A month before The Responsive Eye opened, Tremaine gave a talk titled “A New York Collector Selects” to a group of collectors in which works not owned by the Tremaines were for sale. She mentioned that Seitz had chosen “the strongest and toughest, almost brutal examples” of op art. Given the dizzying quality of some paintings, she joked that her husband, Burton, was negotiating to get the Dramamine concession at the museum for the duration of the exhibition. Then she turned to the four artists whom she found the most interesting: Richard Anuszkiewicz, Bridget Riley, Diter Rot [Dieter Roth], and Larry Poons.

Tremaine explained that it was fortunate to have three paintings by Riley to offer for sale. “There have been none of her paintings available in New York for a long time. I think Riley handles this work with intelligence and skill but I do not find them as beautiful as Poons. I think she is an Apollonian and Poons a Dionysian.” That distinction between the intellectual Apollonian and the emotional Dionysian was one Emily often made about artists.

“Emily Tremaine was very understanding and showed her understanding through her care for and attention to her collection.”

Bridget Riley, 2023

While The Responsive Eye was going on, the Tremaines visited the Richard Feigen Gallery that represented Riley and purchased the painting Turn. In an interview for the Archives of American Art, Herbert Palmer recalled how the gallery came to represent her. “There was Anuszkiewicz, Bridget Riley and Vasarely. They were the big names in those days. And they went to pure, abstract, geometric forms, all of them. The best of them was Bridget Riley, and since that was the hottest new thing, I said to Dick, I think we ought to get her—and show her. And he said, well, we’ll try; she’s getting very hot.”

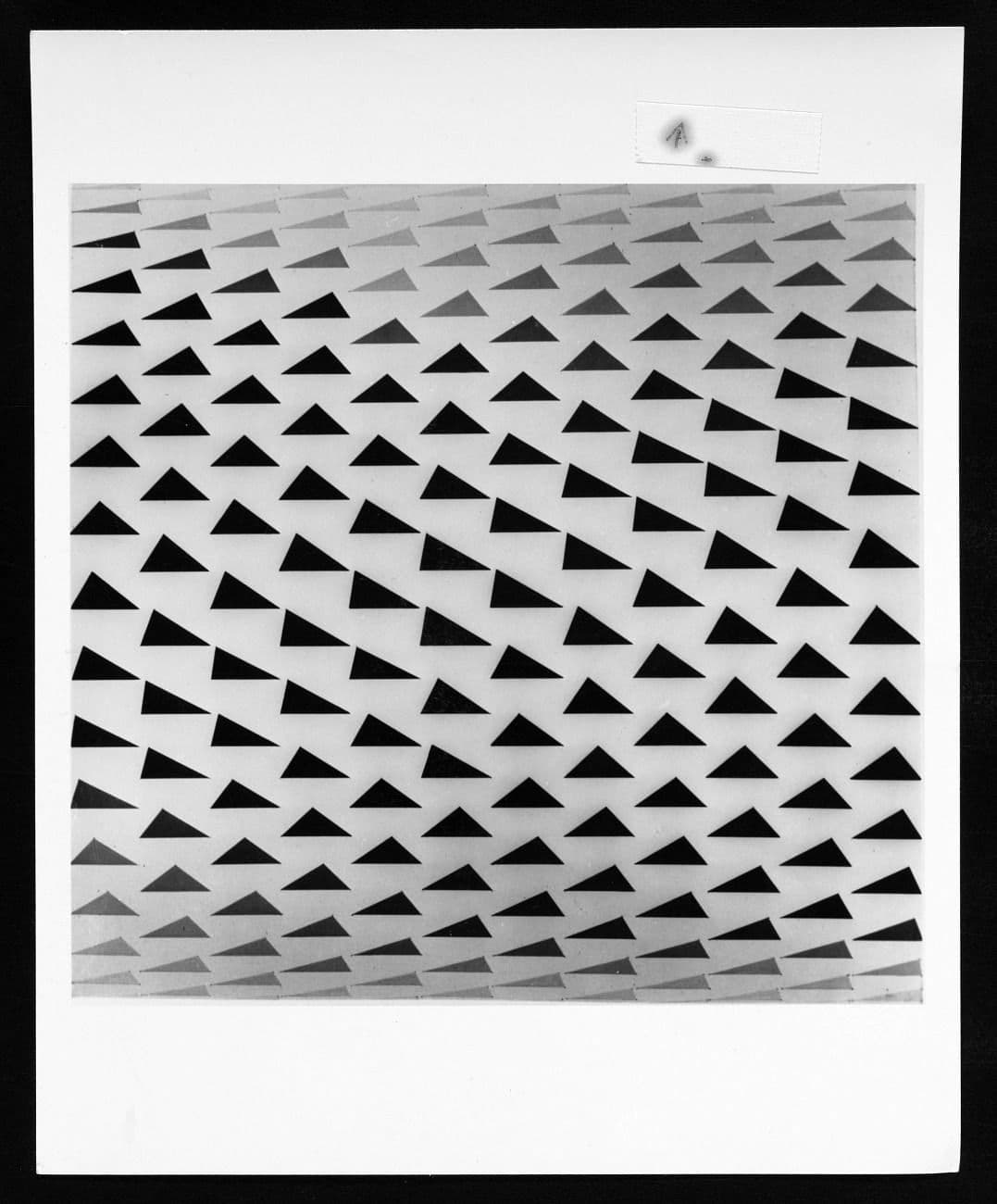

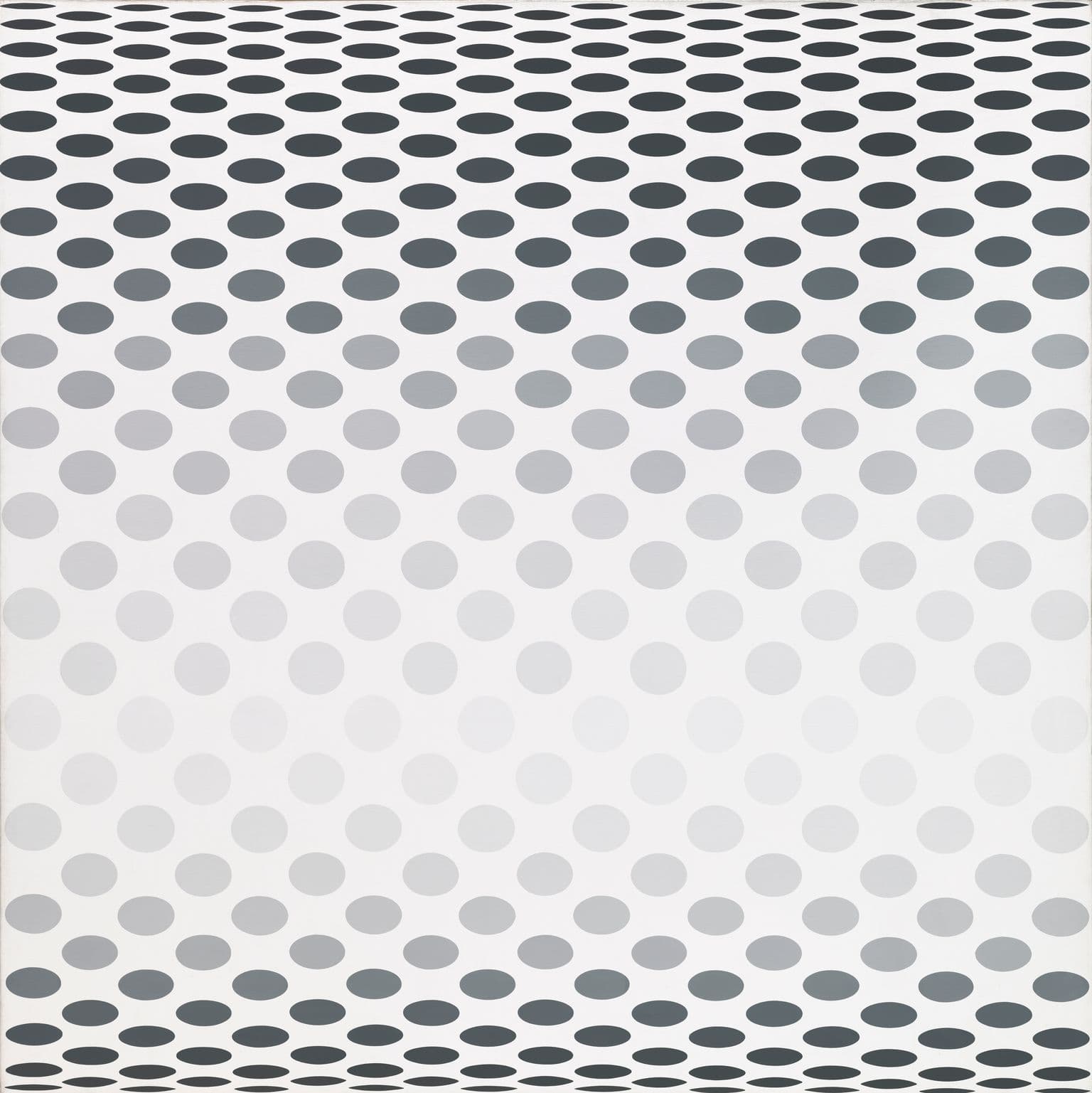

Bridget Riley, Turn, 1964. Originally in the Tremaine Collection. Emily Hall Tremaine Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Turn is based on the inverted triangle that morphs in front of the viewer’s eyes. When it was shown in 1984 at the Wadsworth Atheneum as part of the Tremaine exhibition 20th Century Masters, The Spirit of Modernism, the following description was included in the catalog: “Upward and downward progressions in the piece result from the subtle shifting of one leg of the triangle, while the other two remain constant. In Riley’s work, ambiguities are created by competing systems of visual logic: that of the flatness of the canvas versus the gyrating motion of forms in space.”

“When the Tremaines went on vacation to Florida, Emily took Turn with her, which delighted me. I felt I was part of the family—going on holiday.”

Bridget Riley, 2023

The Tremaines also purchased Balm, a very large 76 ¼" x 76 ¼" canvas that they eventually donated to the National Gallery of Art. Perceptually, Balm calls to mind the shape of a cylinder, vertiginous in its visual spin. Riley’s working method at that time was to make a precise drawing and then to have her assistants do the actual painting. Riley came in for sharp criticism at the time of The Responsive Eye. While it brought her to the attention of the international art world, she said, “I found myself being vulgarized, plagiarized, trivialized and put firmly out of court as an artist…frankly I was hurt.”

Bridget Riley, Balm, 1964. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, National Gallery of Art.

However, Riley appreciated Tremaine’s encouragement. After she returned to England, Riley stayed in touch with her leading to an affirmation of an unusual kind. Every Christmas, the Tremaines selected a work from their collection and had it printed as a Christmas card, much to the delight of art connoisseurs on their mailing list. In 1966, they chose Turn, sending a card to Riley with well wishes for the holidays. Surprised and pleased, Riley requested a few more cards, which Tremaine sent. “I remember when you both came to my ’65 N.Y. exhibition,” Riley wrote. “Incidentally, I shall be over in the U.S. for my exhibition in April and if you wish could check on the condition of Balm.”

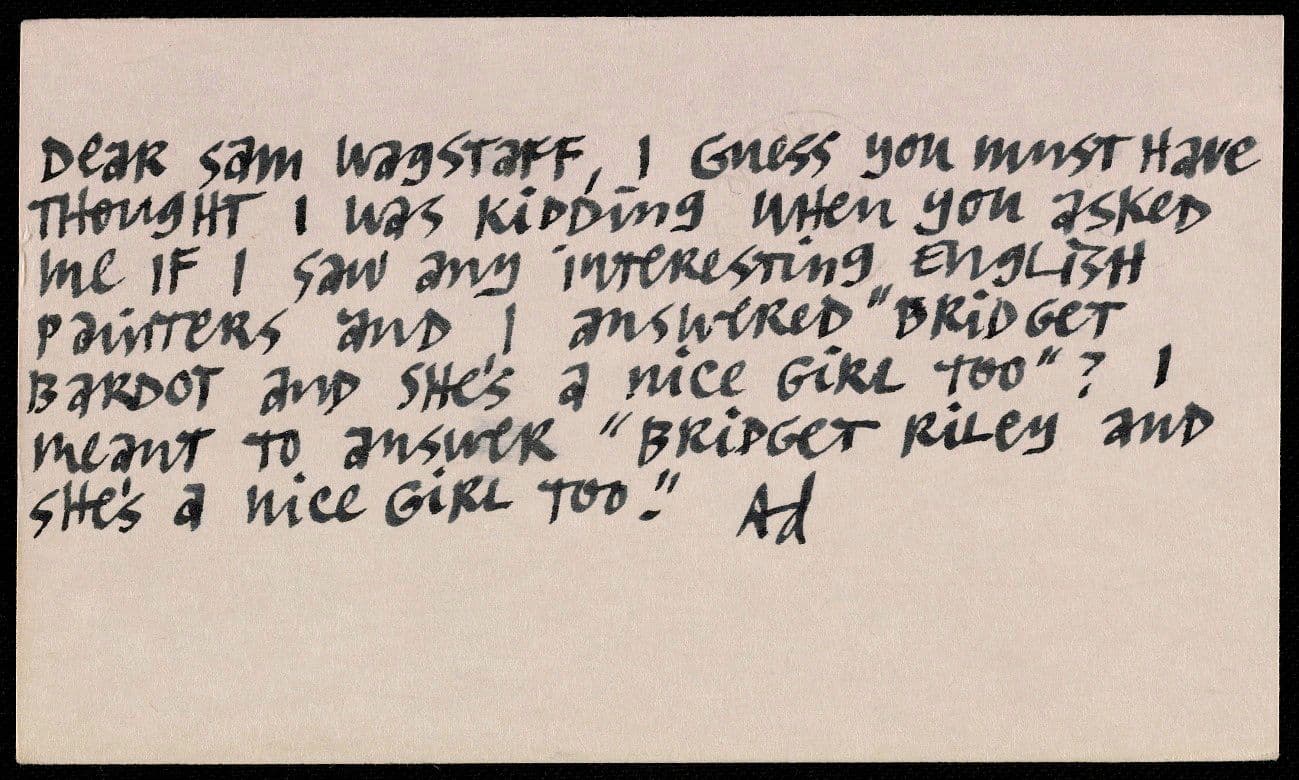

From the Archives

From the Archives

In January 1970 Riley asked Tremaine to loan Turn for a yearlong traveling exhibition to be presented by the Arts Council of Great Britain in collaboration with Gallerie Beyeler Basel and the Rowen Gallery London.“Turn is the best example of a particular phase in the development of my work,” she wrote, “the exhibition would be impoverished without it.” Tremaine readily agreed to lend the painting.

After Tremaine’s death, her portion of the collection was auctioned at Christie’s. Turn was sold on December 15, 1988, for $14,000. That was a decent appreciation from the $900 the Tremaines had paid in 1965. However, it was nothing compared with the appreciation of some of the paintings by men. When Tremaine gave affirmation to a male artist it often lead to an uptick in sales, good critical reviews, and increasing value. However, when she gave affirmation to a female artist, no such uptick, or only a very modest one, occurred.

That failure was not due to anything Tremaine had done or left undone. It had to do with the art-collecting world that was concerned with long-term appreciation in value. Since the art of women did not appreciate as much as the art of men, it wasn’t considered as good an investment no matter its quality. Riley was not the only woman whom Tremaine affirmed; others were Perle Fine, Louise Nevelson, and Barbara Valenta. However, Riley was among the few who lived long enough and worked hard enough to finally receive recognition enough, although equality of success remains elusive.

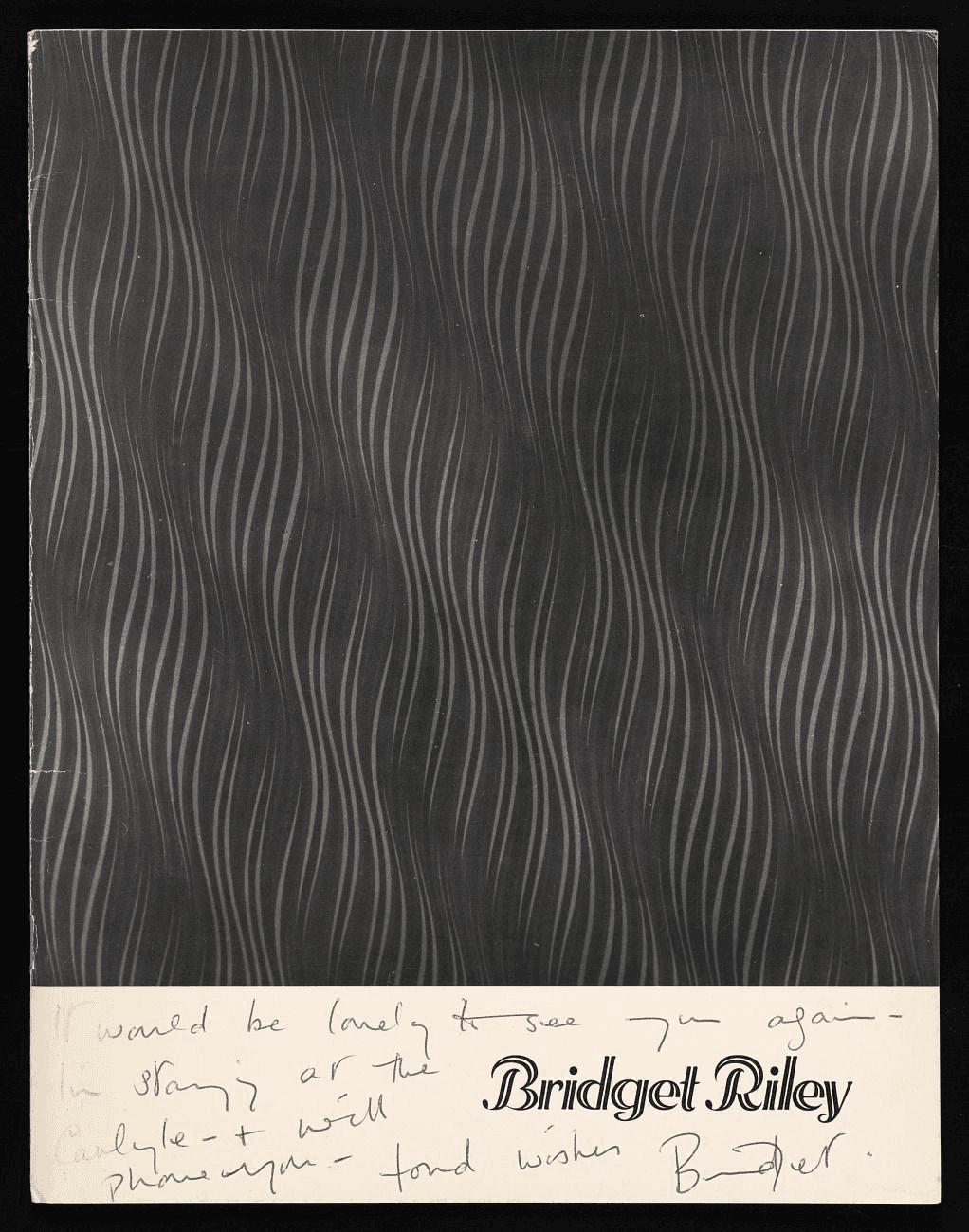

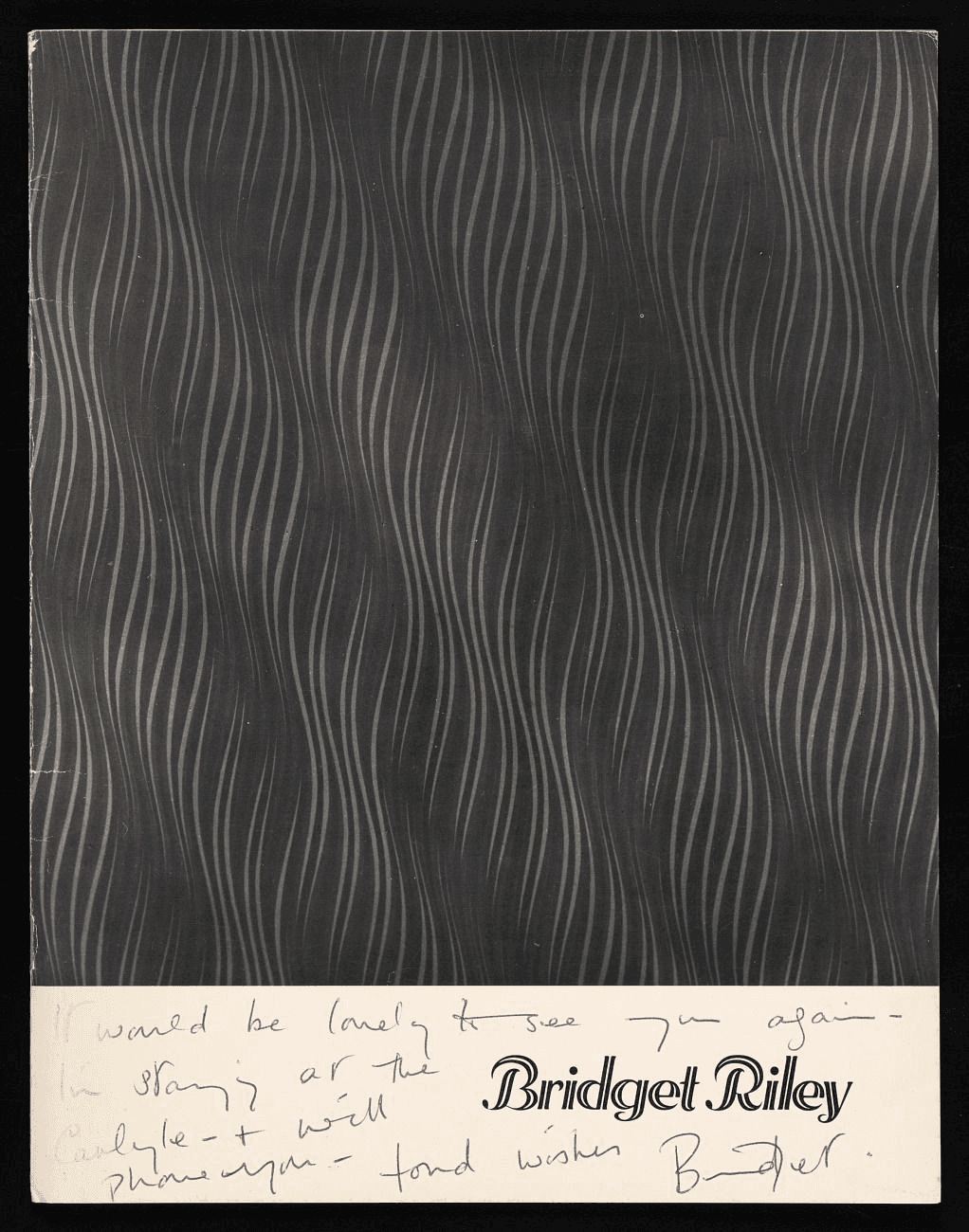

Signed catalogue for the Exhibition of New Paintings by Bridget Riley, May 10-June 2, 1978, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, New York. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Learn more about Bridget Riley on Christie’s: Bridget Riley: ‘Her prints are so emotional. It’s like watching a high-wire act’

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: Bridget Riley, 1963. Photograph by Ida Kar © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: Art, Environment, and Learning Differences.